University of Toronto lab turns McDonald's cooking oil into 3D printing material

Turning water into wine is a biblical reference that symbolizes the transformation of something ordinary into something extraordinary.

That’s exactly what a laboratory at the University of Toronto did when they turned McDonald’s cooking oil into 3D printer resin, as a consequence of the costly materials needed for the Environmental NMR Centre’s 3D printer.

The lab studies “environmental processes at the molecular-level,” explains the program’s director Andre Simpson. “We explore how this information can be used to understand ecosystem and environmental health.”

In order to do so, the lab relies on nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometers – an instrument, similar to an MRI, that’s used to look inside tiny living organisms and understand their biochemical responses to their changing environment. A few years ago, Simpson invested in a 3D printer for the lab, in order to produce custom detection coils for the NMR spectrometer.

“The 3D printer allows us to make complex shapes and parts to make this possible,” Simpson told Yahoo Canada over email.

While making the specific parts wasn’t a challenge, the cost of materials to produce them was. The liquid plastic used in 3D printers can cost up to $525 per litre. So Simpson looked at the substance with scientific eyes and soon learned that molecules used in 3D printing material were similar to those found in cooking oil currently used in fast food restaurants – which wouldn’t have been possible a couple of decades prior.

“Healthy unsaturated fats have reactive ‘double bonds’ that allow us to perform specific reactions,” Simpson explains. “Thirty years ago when fast food chains used mainly saturated fats, this sort of chemistry would not have been possible. In this case what is more healthy for us is also more healthy for the environment.”

Simpson approached McDonald’s corporate office, to see if they’d be interested in donating used cooking oil from their restaurants. They advised him to find a franchise owner who was willing to share the used oil. Eventually a partnership was formed with a McDonald’s near the campus.

Simpson describes the experimentation process to figure out how to turn cooking oil into a more concrete substance as similar to “getting the recipe right in baking or cooking.”

“We kept optimizing the mixing ratio of the chemicals and the heating until we got the highest amount of material that could be converted into plastic,” he says.

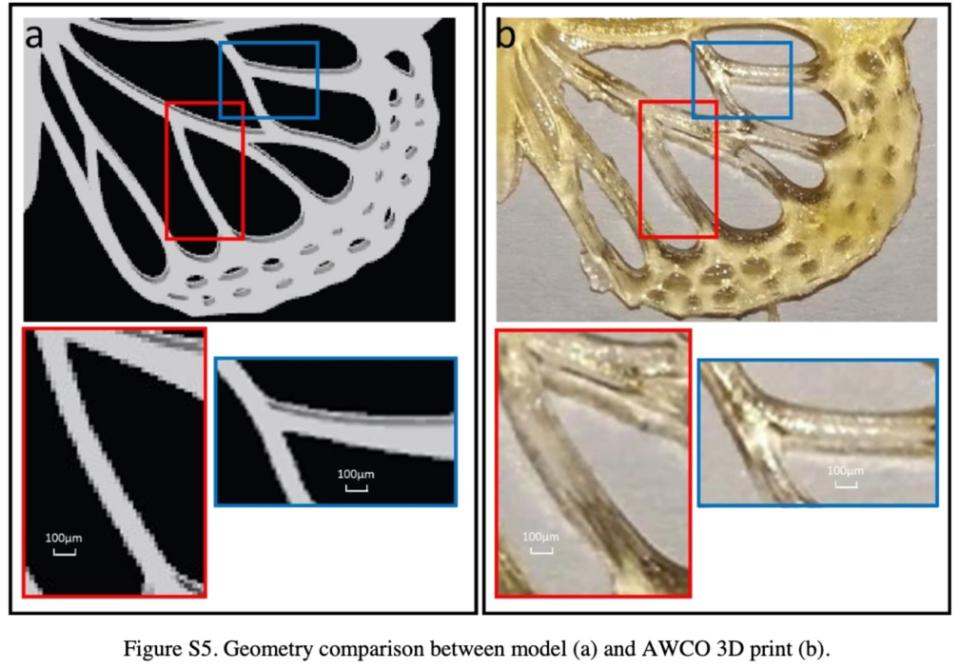

Once they had figured out how to optimize the ideal 3D printing conditions, taking into consideration how much light was used and how long to expose each pixel, researchers managed to convert the liquid plastic into a solid plastic shape of a butterfly.

The resin that the researchers were able to produce, which is also biodegradable, costs 30 cents a litre, which is dramatically less than 3D printer material.

“Much of the cost of recycling is the transportation of used oil. Hence, it may be transformative for recycling programs if high value commodities can be manufactured easily from waste cooking oil,” says Simpson. “We hope it will remove the financial barriers making it possible for oil to be reused and recycled.”

The newly discovered resin is also part of a sustainable cycle.

“As the final prints are biodegradable, the carbon should return to the soil thus closing the carbon loop – plants to oil, oil to plastic, plastic to soil – while avoiding the use of fossil fuels from which conventional plastics are derived. “

Simpson sees a future in the conversion of cooking oil to 3D printable resin. He explains that since the resin sets in sunlight – and putting 3D models in sunlight is a common practice to further harden and cure resins – it’s possible the cooking oil resin could have a range of other uses beyond 3D printing. Examples include a plastic concrete that cures on site or a UV curing glue that turns into a self-curing plastic sheet, walkway or cover that floats on water.

Whatever happens next, there seems to be interest. Once the research was published in an industry publication, Simpson was flooded with inquiries.

“I have been shocked by the number of people that are interested in this,” he says. “Everyone from the environmental industry, 3D printing industry, food industry and the general public.”