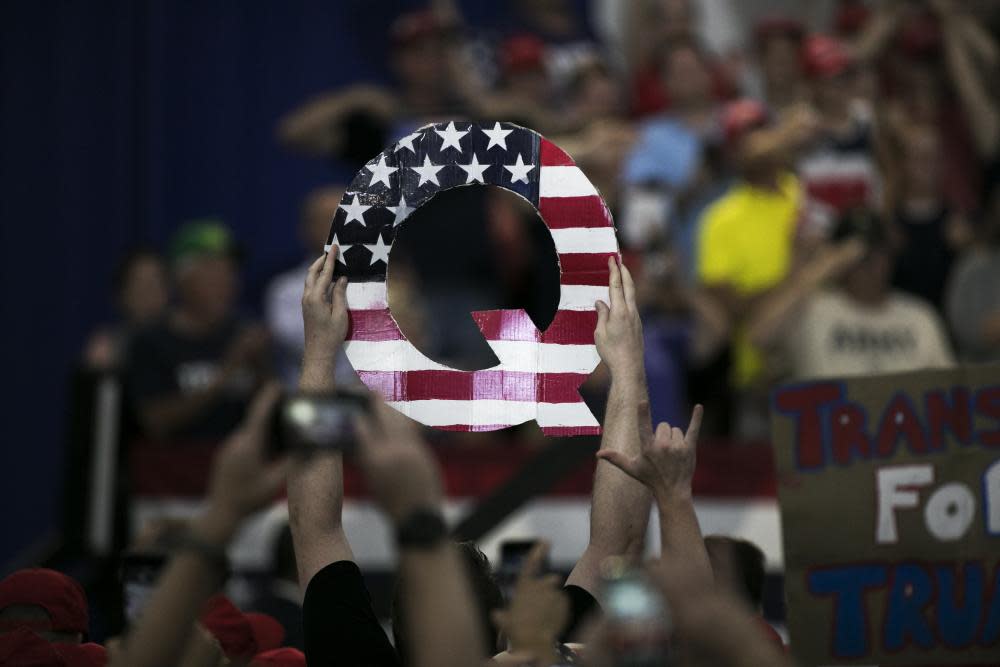

'They need voters': QAnon is finding a home in the Republican party

According to one congressional candidate for America’s House of Representatives, Covid-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement are a screen “for pedophilia and human trafficking”.

Another has claimed the US has a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to take this global cabal of Satan-worshiping pedophiles out”, while several others running for national office have posted cryptic memes hinting at a powerful global elite that must be abolished.

These believers in QAnon, a conspiracy theory labelled a potential domestic terror threat by the FBI, are all running for national office – not as fringe independents, but as Republican candidates.

Related: Down the rabbit hole: how QAnon conspiracies thrive on Facebook

In some cases they have been backed by Republican money, and promoted by Donald Trump himself, and in certain Republican heartland states, the QAnon candidates are even likely to be elected in November.

Marjorie Taylor Greene, from Georgia, is among the QAnon supporters with the best chance of winning in November. She has also been the most strident with her beliefs.

“Q is a patriot,” Greene said in 2017, referring to her belief in the conspiracy theory’s anonymous online poster who claims to have knowledge of a secret ring of powerful, deep-state sex-traffickers and pedophiles, and is said to be a part of the Trump administration.

“He is someone that very much loves his country and is on the same page as us, and he is very pro-Trump. He appears to have connections at the highest levels.”

Greene is running for the state’s 14th congressional district, where in August she needs to overcome a Republican opponent she has already bested in the primary, then challenge a Democrat for the reliably Republican seat. Her bid will probably be helped by an endorsement from Trump in June, but if she and others win in November, experts say it could boost the popularity of the theory even more by arriving in the nation’s halls of power.

“If these people do get into office – and I think several probably will, because of the nature of the districts their running in – this potentially gives them a platform to spread QAnon,” said William Partin, a disinformation analyst at Data & Society, a non-profit research organization.

“I think it’s clear at this point that it’s detrimental in a wide range of ways, in terms of interpersonal relationships, actual criminal activity and violence.”

It was a QAnon believer who, heavily armed, entered a DC Pizza parlor in December 2016, prepared to take on a child sex ring supposedly being run by Hillary Clinton out of the restaurant’s basement.

In 2019, the alleged New York mob boss Francesco Cali was shot and killed by a man who said he was obsessed with QAnon and believed Cali was part of a deep state conspiracy against Trump. In April this year a woman inspired by QAnon videos traveled to New York armed with more than a dozen knives, in an alleged attempt to kill Joe Biden.

None of those incidents have stopped candidates such as Angela Stanton King – like Greene, a Georgia-based candidate for Congress – from posting QAnon messaging.

On 16 July she claimed on Instagram that Covid-19 and Black Lives Matter were a screen “for pedophilia and human trafficking”, a few days after suggesting on Twitter that the election was about “globbal [sic] elite pedophiles trafficking children”.

Media Matters, a not-for-profit progressive research center which monitors misinformation, has counted 67 current or former congressional candidates who have embraced QAnon.

Along with Greene and Stanton King, Lauren Boebert, running for the House in a traditionally Republican district in Colorado, has spoken approvingly of QAnon.

“Everything I’ve heard of Q, I hope that this is real because it only means America is getting stronger and better”, Boebert said in an interview in May. Like some others, she has since distanced herself from the movement in the wake of media attention.

Others include Mike Cargile, a House candidate in California, who included the hashtag “WWG1WGA” a QAnon slogan which stands for “Where we go one, we go all” – in his Twitter profile, and Billy Prempeh, running in New Jersey, who posted a photo of himself next to a QAnon flag on Facebook.

Elsewhere, Jo Rae Perkins, the Republican candidate for Senate in Oregon, claimed in January there is a “very strong probability/possibility that Q is a real group of people, military intelligence, working with President Trump”.

Travis View, the co-host of the QAnon Anonymous podcast, which tackles the conspiracy theory, said that QAnon followers tend to be “extremely politically active”, both in terms of voting and promoting candidates online.

That could be one reason why there has so far been little condemnation of these candidates, or of QAnon itself, from senior Republicans.

“I cannot find a Republican leader who has said a bad thing about QAnon,” View said.

“I’m so fascinated by the weird line that Republican leadership is walking right now. Republicans cannot afford to spare a single vote, so they need to get as many voters on board as possible.

“That may explain why they’re doing this weird dance where they don’t want to say a bad word about QAnon, but also not give any explicit endorsement to QAnon either.”