Waterside bliss under threat on France's Canal du Midi

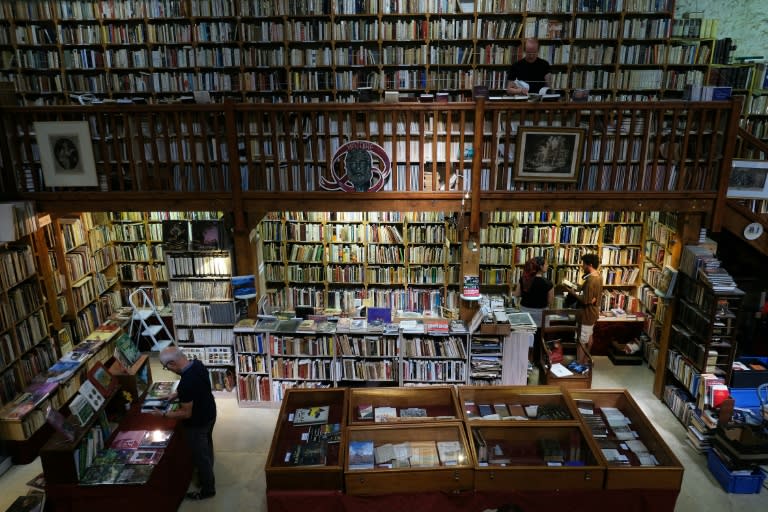

France's Canal du Midi was once a bustling commercial artery crowded with lock keepers, boatmen and barges weighted down by wine and wheat. These days, 350 years after it was carved out of the soil of southwestern France, its banks and waters have become a haven for slow-living locals, artists and prosperous professionals. They are passionate about this waterway, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that they call home, but some are worried that their paradise may be threatened by a surge in tourism and the effects of a tree-killing fungus. "It's a lifestyle I wouldn't change for anything in the world," says Mariance Martinel, who runs a bed and breakfast on her houseboat. Constructed at the height of the reign of Louis XIV and brainchild of engineer Pierre-Paul Riquet, the 240-kilometre (150-mile) waterway links the city of Toulouse with the Mediterranean. The waterway also continues northwest of Toulouse as the Canal de Garonne, leading to the Atlantic, with both sections known as the Canal of Two Seas. For Emma Tissier, the attraction is that "you are neither in the countryside, nor the city -- you are totally disconnected from the urban world." She and her partner share a 29-metre (90 feet) long "peniche" or barge in Ramonville, a small port just outside Toulouse. Most of the canal's residents live on their boats and arrived in waves starting in the 1990s. - Thousands of trees felled - "We've got a little of everything here... Hippies, Airbus employees, French and Dutch people," says Jean-Yves Delmas, president of a Toulouse association of canal users and owner of a pink and turquoise peniche. They all share a strong desire to protect the environment and respect for the canal. "It's our environment and we cherish it," says Delmas, a former sales manager who is barefoot and wearing bermuda shorts. Care for the environment means using biodegradable cleaning materials and paint, using water purification systems and getting rid of rubbish that has been dumped in the water as well as along the banks. "We look after our surroundings," explains Tissier, a 40-year-old self-employed graphic designer and mother who delights in the soft quality of the daylight which filters through the trees lining the canal. But certain issues trouble her -- not least the battle to save the remaining plane trees bordering the canal, thousands of which have been felled to stop the spread of a microscopic fungus that has wrought havoc over recent years. France's waterways authority VNF has vowed to replace all trees infected by Ceratocystis platani, believed to come from contaminated wooden ammunition crates used by US troops in World War II. - Explosion of tourism - Worse yet are the pleasure craft and rented houseboats that zip along, churning up waves that erode the banks, complains Tissier's English partner Caspar Galsworthy, 55, who says he spends his time "patching up rickety old boats." Not everyone sees it in such a negative light, with Claudine Wytrowa, who runs a grocery business from her barge, quick to point out that the canal "is alive and it changes to reflect the times." The biggest upheaval of recent times was the canal's designation as a world heritage site in 1996, prompting a boom in the number of visitors. Since then the canal's development "has gone a lot faster," says Nelly Gourgues, who runs a family bookshop in Somail, a village along the canal. "Now, boats from around the globe stop here" dropping off a steady stream of British, German, Dutch and Russian tourists, she says. "There's been an explosion of tourists," agrees Joel Barthes, 61, who has spent more than half of his life on the canal and has the weatherbeaten skin to prove it. - Changing times - He makes iron and wooden sculptures to embellish the lock at Puicheric, a small town a few kilometres inland where he is the lock master. "For 11 years I worked the lock gate cranks. In the old days, lock masters had a washboard stomach and big biceps and were respected." With the arrival of automated lock gates and private companies to carry out repairs and cut down the stricken trees "that spirit has gone." But leaving is out of the question, he says. "You'd have to send in the police to drag me away," he grins.