The Westminster lobby system is at the heart of a press freedom fight

Lobby is not the best word to associate with journalism. As a noun it’s a room which is inside and yet not; as a verb it stands for trying to influence politicians. Yet the “lobby system” in parliamentary reporting, a relic of the 19th century, is now at the centre of a very 21st century fight for press freedom.

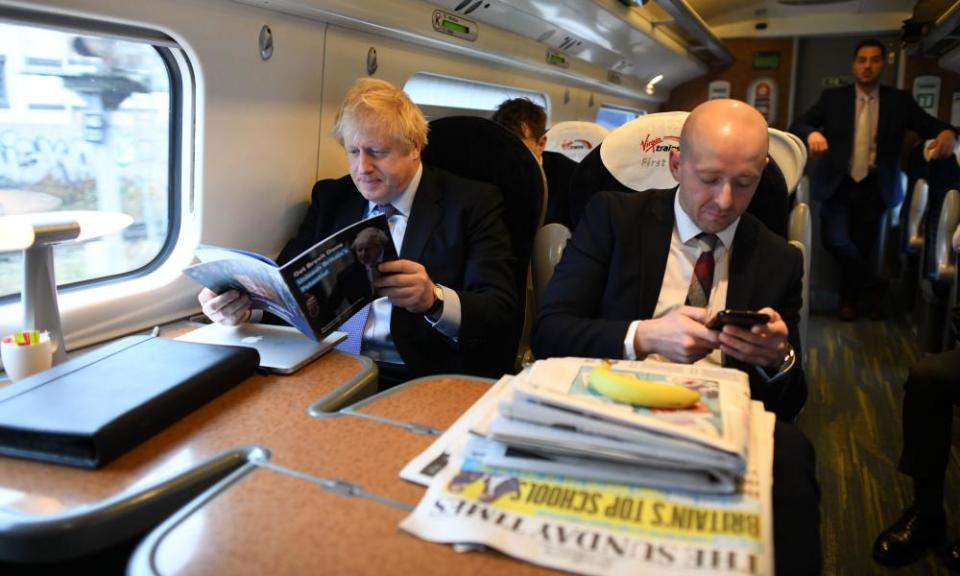

The government’s move to change the location of the traditional twice-daily briefing system, from the Commons to 9 Downing Street, is hardly the most egregious insult lobbed at journalists from a government that has already banned newspapers from its campaign bus, spurned a flagship BBC news programme and threatened to review Channel 4’s remit because it refused to do its bidding.

In the face of threats to end the BBC’s licence fee, moving lobby briefings feels like the sort of insider moaning unlikely to garner much sympathy from non-journalists.

Yet the changes, announced without consultation days before Christmas, are straight from the playbook of a game already being dangerously played out in the US. White House briefings were initially restricted, then dropped; 2020 has started with significant restrictions on how correspondents cover the impeachment hearings against the president, all in the name of security. For politicians on both sides of the Atlantic, making life difficult for journalists whose job it should be to ask questions and hold them to account seems to have become a consequence-free activity.

The lobby system in the UK would, perhaps, be a strange hill for press freedom fighters to die on. The fact that journalists must receive accreditation to join, the strange rituals such as the “huddles” which attend big announcements, and the over-frequent use of “friends” and “people familiar with” as “sources”, does little to dispel the idea that the lobby may be a little too close to power – again not quite an insider, but lurking in the corridor outside.

For politicians on both sides of the Atlantic, making life difficult for journalists seems to have become a consequence-free activity

Yet the system – which consists of 15 daily newspapers, seven Sunday papers, six news channels, 12 news agencies, three magazines and, perhaps most importantly, the local titles that can still afford to send a reporter to London – offers journalists the chance to question civil servants and government spokespeople about new legislation and other matters, twice a day during parliament. It may not be perfect, but the alternative – providing no access, or only on the government’s terms – is far worse.

An important principle is at stake. For the first time in history, lobby journalists will have to ask permission from the government to be briefed by the PM’s official spokesman, rather than just being able to ask questions by dint of having a lobby pass.

Concern over the latest move led every national newspaper editor – including Chris Evans at the Telegraph, which until recently employed the prime minister – to join forces with more than a dozen editors from broadcast and regional media to condemn the plans in a letter sent by the Society of Editors.

There are two big fears over the government’s changes. First, that it will be able to prevent unfavoured journalists from passing security – witness Johnson banning the Mirror reporter from his bus during the campaign. The Telegraph’s Christopher Hope, current chair of the lobby, wrote of its concerns that forcing reporters to go through an extra layer of parliamentary security “allows the current or future governments to refuse access to journalists it may not approve of”.

And second, there are concerns that the changes provide an extra layer of bureaucracy for regional news reporters who already have to cover both government and parliament on their own. One reporter typically struggles to be in two places at once – the Commons and Downing Street.

There is little sign that the government cares, of course. Lee Cain, the prime minister’s spokesman, told the lobby that the decision had been made and “needs no further discussion”.

The letter to Johnson from the Society of Editors suggests surprise that this treatment could be meted out by a man who spent three months seconded to the Wolverhampton Express and Star. “With your background as a journalist in both the regional and national press, you will be aware of just how important access to those at the heart of government is in producing accurate and balanced coverage.”

Whatever Johnson’s background, he has learnt from both his stonking majority and the election of Trump that denying access and respect to the media does no harm whatsoever at the ballot box. Indeed, refusing to face questions about outright lies – whether 40 new hospitals or 20,000 “new” police officers – has appeared so far to merely increase the number of websites set up to debunk them, rather than votes for political opponents.

While making it harder for journalists to ask questions, the Downing Street team engages in new extremes of doublespeak. They continue to spout support for freedom of the press, most notably in the last Queen’s Speech, but also in the Conservative manifesto last year, which promised to “support local and regional newspapers, as vital pillars of communities and local democracy”.

Rebecca Vincent at Reporters Without Borders sees parallels between the behaviour of the UK over political coverage and the US. After the Trump administration’s campaign of intimidation against “mainstream media’” as “fake news”, and the scrapping of daily White House briefings, the US fell down RSF’s world press freedom index into the “problematic” category for the first time, ranked 48th out of 180 countries.

“The UK is also not where it should be, ranked 32nd, and we should be taking steps to improve our own press freedom performance rather than following the US down,” she said.

Among the organisation’s chief concerns is the review of the Official Secrets Act, using the US system as a model. The previous proposals to change the law in 2017 would have made it easy to label journalists and others as spies and jail them for up to 14 years.

If it isn’t too late to make a prediction for this new year, leaders of two of the oldest bastions of press freedom in the world – the UK and US – will continue to add restrictions and, in other ways, make life difficult for the media, acting with impunity in the face of no criticism from anyone other than journalists themselves. Given the importance of journalism in a democracy, something has to be done.

Fighting against restrictions is one thing, but changing perceptions – often entirely unjustified that the industry is a club – is another. Widening diversity of reporters and reporting would help. So would continuing to shout.