Why Harold Pinter’s widow feels his screenplays deserve greater recognition

He was one of Britain’s most celebrated playwrights, whose work – including The Birthday Party, The Homecoming and Betrayal – transformed the theatre world in the 1960s and 1970s. But now, to mark what would have been Harold Pinter’s 90th birthday, his widow, Lady Antonia Fraser, has spoken of her desire to see wider recognition of her late husband’s impact on British cinema.

Pinter, who was awarded the Nobel prize for literature 15 years ago, died three years later at 78, after a writing career spanning more than half a century.

“I now have the agreeable habit of showing his films, especially the ones people don’t know so well, in a little private cinema in Soho whenever I can,” she said in an interview staged by the Chiswick Book Festival. Among largely forgotten gems, Fraser lists the 1989 film Reunion, 1976’s The Last Tycoon and Langrishe, Go Down from 1978, starring Judi Dench and Jeremy Irons.

Fraser, 88, who was married to the playwright for 28 years, said she felt his screenwriting was regularly overshadowed and said she held out hope that his screen work might be celebrated in a season of films for the general public.

One of her favourite films, she explained, was The French Lieutenant’s Woman, which Pinter adapted from the novel by John Fowles. “It is the dialogue that makes it work so well. I love that film,” she said.

Pinter’s plays are often characterised as “menacing”. His commissioned adaptations of novels for the cinema are wider-ranging, though still often stamped with trademark curt and sinister exchanges. Among the best known are The Servant, Accident and The Go-Between, each directed by Joseph Losey, but he also wrote screenplays for the stylish 1960s thriller The Quiller Memorandum, F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Elizabeth Bowen’s The Heat of the Day, starring Michael Gambon, Michael York and Patricia Hodge.

When Fraser showed this last, little-known, film, she said her audience were particularly impressed. “No one could understand why it is not better known,” she said.

Writing for the stage consumed Pinter’s imagination, but Fraser said he had another routine for screen work: “There was a great difference in his habits. If he was doing a commission, which would be a screenplay, as he never did a screenplay on spec, it was work. He sat down and did it. Whereas with a play, he might work all night. When he wrote his last play, Celebration, set in a restaurant, we were staying in a lovely house in Dorset we used to rent, and one night he swung out of bed. I asked what was the matter. He said: ‘It is that waiter. He won’t let me sleep.’ It was never like that with a film script.”

However, Pinter did spend a year working on a screen adaptation of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past that was never made.

Fraser met Pinter when they were both married and in their early 40s. The romance provoked media attention which Fraser said “would seem ridiculous now”.

“We were two middle-aged writers, not pop stars. We were not Beyoncé,” she said. “Though it is probably good for the soul to have the press flocking around your doorstep, asking you idiotic questions.”

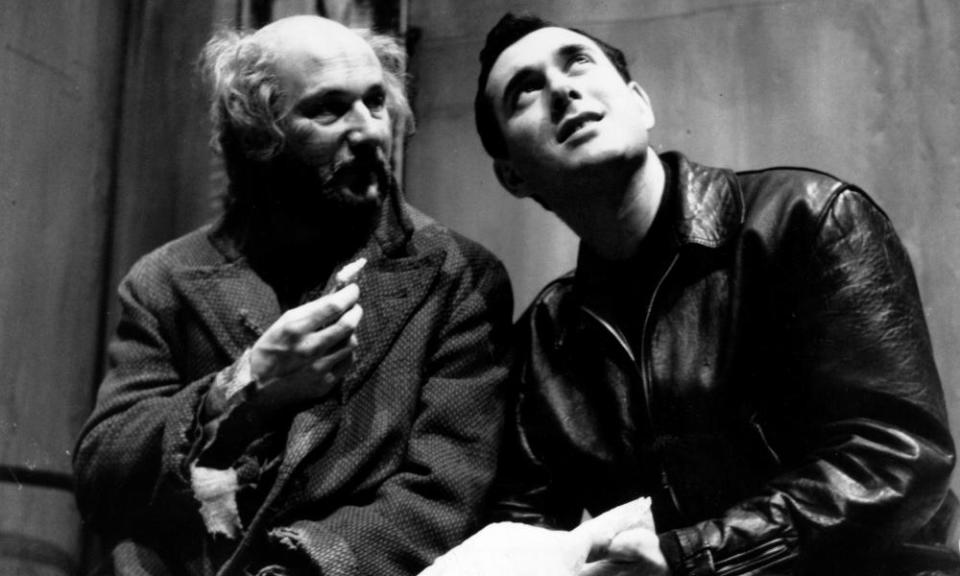

Some of Pinter’s early work was for television and was shown by ITV after Sunday Night at the London Palladium. His second stage play, The Birthday Party, closed after a week following initial bad reviews, but he made his name with The Caretaker, first produced 60 years ago. It became the must-see West End show in a week that also saw Orson Welles directing Laurence Olivier on stage.

It is also one of two Pinter plays inspired by real London flats. Pinter lived in Chiswick in the late 1950s with his first wife, the actress Vivien Merchant, and their son Daniel. On the way downstairs he spotted a homeless man talking to another resident. The two became The Caretaker’s stage characters Aston and Davies.

In 1975, Pinter left Merchant for Fraser, having previously had a long relationship with Joan Bakewell, an affair conducted in part in a flat in Kentish Town, London. The experience inspired Pinter’s best-known work, Betrayal, where the flat is moved to Kilburn.

Fraser, however, said there were “enormous” features of this play that were absent from real life, including “the non-homoerotic male friendship” at its centre. “He simply didn’t have that with Joan’s husband. It is irrelevant. We were very much together when he was writing it, and he felt it was his play. Not someone else’s,” she said.

Pinter, who was born and raised in Hackney, east London, was a keen sportsman and lifelong cricketer. Expressing her sorrow that he did not live longer, his widow said she felt “he would have enjoyed [lockdown] because of the chance it offered to read and write; all but for one thing: no cricket”.

The playwright had originally trained as an actor, first at Rada and then at the Central School of Speech and Drama, and continued to take acting work throughout his life.

“He had always felt, he told me, that if his career as a playwright had not taken off, his acting career would have grown and got better as he had become a character actor.”

Although in frail health after a cancer diagnosis in December 2001, Pinter continued to act on stage and screen, performing in Samuel Beckett’s monologue Krapp’s Last Tape at the Royal Court theatre in 2006.

He died on Christmas Eve two years later.