Yet Again, A Judicial Counterrevolution Looks To Chain The Country To An Imagined Past

(Photo: Illustration: HuffPost; Photo: Getty Images)

At his presidential inaugural on March 4, 1857, President James Buchanan, a Northern Democrat aligned with the South’s slavers, took to the steps of the Capitol and preemptively announced the result of an as-yet-unreleased Supreme Court decision that would give a “settlement of the question of domestic Slavery in the Territories.”

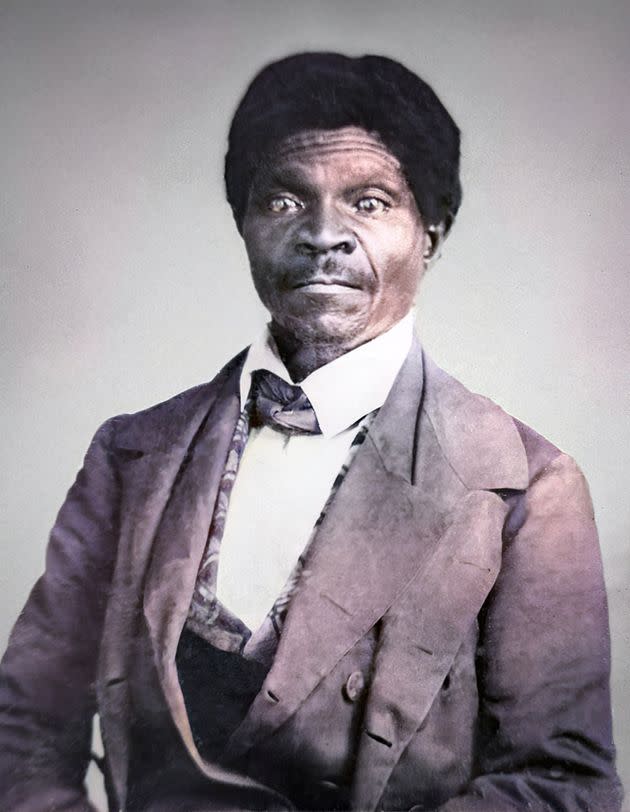

Two days later, Chief Justice Roger Taney read his majority opinion in the case of Dred Scott v. Sanford. Black people, Taney wrote, are to be “regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

The pro-slavery court majority leaked the outcome of the case to Buchanan months earlier. They wanted his help in securing the vote of Justice Robert Grier, a Pennsylvanian like Buchanan, for Taney’s decision. As a Northerner, Grier could give the decision a patina of national support, as opposed to coming from an all-Southern bloc. Grier, a supporter of slavery, happily complied.

By repealing the national ban on the establishment of slavery in territories located north of the Mason-Dixon line and returning the decision to the territories, Taney hoped the decision would end the agitation around the slavery issue in favor of his pro-slavery views. For his part, Buchanan hoped it would also destroy the new and growing anti-slavery Republican Party by taking their main issue, prohibiting slavery in the territories, away from them.

Today, another counterrevolution is under way at the Supreme Court. Five conservative justices, led by Justice Samuel Alito, overturned the the 49-year-old decision in Roe v. Wade granting women the right to an abortion. The decision largely hews to a draft opinion published by Politico in May.

Like the court in Dred Scott, today’s robed counterrevolutionaries reveal themselves and the court as nakedly political and partisan actors. The court has always been a political entity, but it seeks to mask this nature with a mythology hiding its political nature in legal theories, citations to precedent and popular conceptions of the rule of law. It occasionally bares its political teeth to the public in cases like Dred Scott. And now it’s done the same with its opinion overturning Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

The Supreme Court, in the 1857 case of Dred Scott (pictured), ruled that Black people were "so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." (Photo: Gado via Getty Images)

Alito’s opinion carries with it key features of the Dred Scott decision. It features nasty language demeaning the subject of the opinion and relies on an inaccurate history of law and precedent to justify the political goal he wishes to achieve.

Taney’s Dred Scott opinion drips with contempt for anyone who could possibly think that Black people could be citizens of the United States or that anyone in the Founding generation would approve of such belief. Taney argued that the United States, as a nation formed for the benefit of the white man, is both originally and fundamentally racist towards Black people. This racism was inborn from English law, belief and custom. And it was, therefore, ineradicable.

“[F]or more than a century,” before the founding, Black people were “regarded as beings of an inferior order,” who were “unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations,” Taney wrote.

“This opinion was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race,” he added, therefore, “[n]o one seems to have doubted the correctness of the prevailing opinion of the time.”

Taney was saying that the original sentiment of colonial and revolutionary era white Americans should apply to the law forever. This has a familiar ring to modern ears. Its sound can be heard in Alito’s opinion.

“The inescapable conclusion is that a right to abortion is not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions,” Alito writes. “On the contrary, an unbroken tradition of prohibiting abortion on pain of criminal punishment persisted from the earliest days of the common law until 1973.”

Elsewhere, Alito writes that Roe and Casey “must be overruled,” because the “Constitution makes no reference to abortion,” and “no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision,” because “any such right must be ‘deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition’ and ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.’”

Like Taney, Alito’s opinion determines that the law in America can be fixed based on sentiments expressed in the 18th century and earlier ― at least when fixing such sentiments helps reach the desired policy result.

As Taney provided his own history of U.S. law to show the country to be originally and fundamentally racist, Alito provides his own history lesson to show the country never provided reproductive rights to women. In both cases, their history is cherry-picked to help them reach their desired result.

When Taney claimed that it was a “fixed and universal” opinion that Black people were not meant to be included in the grant of rights provided to citizens in the Constitution or “all men” in the Declaration of Independence, he provided a litany of laws treating Black people as “inferior” to back up his claim.

Justice Samuel Alito's majority opinion overturning the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision stated that Americans are not due rights to an abortion because it is "not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions." (Photo: SAUL LOEB via Getty Images)

But at the time of the adoption of the Articles of Confederation, the precursor to the Constitution, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey and North Carolina provided citizenship and voting rights to all “free native-born inhabitants,” Justice Benjamin Curtis noted in his Dred Scott dissent. These state constitutions continued to provide such rights through the adoption of the Constitution.

Clause 4 of the Articles of Confederation stated: “The free inhabitants of each of these States, paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice, excepted, shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several States.”

The exclusions here did not include any mention of race or prior enslavement, Curtis noted. When delegates met to write and adopt the Articles of Confederation, they rejected an amendment from the South Carolina delegates to change the phrase “free inhabitants” to “white inhabitants.”

Alito’s claim that the right to an abortion is not “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” rests on similarly faulty ground. To back up his claim that abortion rights are not “deeply rooted,” Alito cites the fact that 28 of the 37 states banned abortion throughout pregnancy at the time of the adoption of the 14th amendment, which contains the Due Process Clause that the court in Roe relied on to grant abortion rights.

“Alito’s argument about how the common law treated abortion is also remarkably weak,” Adam Winkler, a constitutional law professor at UCLA Law School, tweeted on Wednesday. “Nearly all the evidence that he cites shows that *pre-quickening* (about 16 weeks), abortion was not criminalized.”

“Quickening,” means the moment the mother can feel the fetus move. Every state at the founding allowed for abortion up to quickening, according to a review of the legal history by University of California-Davis law professor Aaron Tang.

States later admitted to the Union that Alito includes in his account, like Louisiana and Nebraska, only banned abortion by “drug,” “poison,” or “noxious substance.” And, Tang noted in a tweet, Alito includes Florida’s abortion ban, even though it was adopted after the 14th amendment.

“These are not just incidental historical mistakes,” Tang tweeted on Wednesday. “The entire crux of Alito’s conclusion that there’s no [right] to abortion at any point in pregnancy is his belief that most states banned it when the [14th amendment] was adopted, such that it’s not ‘deeply rooted in history.’”

Even if we are to grant Alito the fact that no state constitution granted the right to an abortion, this simply reveals the denial of a right to a class of person ― women ― who were “legally regarded as second-class citizens, kept out of medical institutions and public office and banned from owning property,” as HuffPost’s Lydia O’Connor writes.

Reproductive rights advocates protested ahead of the decision with allusions to slavery. (Photo: JASON REDMOND via Getty Images)

“There were no women among the delegates to the Constitutional Convention,” writes historian Jill Lepore in The New Yorker. “There were no women among the hundreds of people who participated in ratifying conventions in the states. There were no women judges. There were no women legislators. At the time, women could neither hold office nor run for office, and, except in New Jersey, and then only fleetingly, women could not vote. Legally, most women did not exist as persons.”

The echo of Dred Scott in Alito’s opinion did not go unnoticed by the dissent by liberal Justices Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor.

″[The decision] says that from the very moment of fertilization, a woman has no rights to speak of,” they wrote, clearly invoking Dred Scott’s infamous line that Black people “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

After 50 years seeking all encompassing power, the conservative legal movement has reached its apotheosis. It climbed the mountaintop after Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election despite losing the popular vote by nearly three million votes. He then became the first president since Ronald Reagan to appoint three justices to the court, thanks in part to Sen. Mitch McConnell’s (R-Ky.) refusal to hold a hearing on President Barack Obama’s nominee Merrick Garland in 2016 and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s refusal to retire and have Obama appoint her replacement.

The court’s six-vote conservative supermajority, founded on the anti-majoritarian pillars of the Senate and the Electoral College, is now finishing the agenda that conservative presidents going back to Ronald Reagan could not do through legislation or executive action.

Taney’s counterrevolution sought to quell the growing anti-slavery sentiment in the North, where the population was expanding and the economy growing, by chaining the nation to his version of the past. Today’s conservative supermajority, which came to be just as the more racially diverse and liberal Millennial generation became the largest living generation in 2019, is built to do the same.

Now the dead hand of the past wraps its fingers around this generation’s future to drag it backwards through a series of reversals of the 20th century Rights Revolution and what is left of the New Deal state.

It remains to be seen whether this court’s opponents or their leaders can mount the kind of political mobilization that opponents of Taney’s court did to counter the anti-majoritarian powers of their day. Either way, a bitter political battle awaits.

This article has been updated to reflect the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade on June 24.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.