12 Black Inventors and Their Innovations That Shaped the World

When asked to name a Black American inventor, many people might think of George Washington Carver and peanut butter. But this is actually a myth. Carver did not invent peanut butter, but he did devise over 300 different uses for peanuts — including dye, soap, coffee and ink — and a plethora of uses for sweet potatoes.

Still, there are hundreds of other unsung Black inventors who have shaped the world with their innovations. Lonnie Johnson invented the Super Soaker, Mark Dean co-invented the IBM personal computer and James West invented the widely used foil electret microphone. Now let's look at 12 other groundbreaking innovations from Black inventors.

12. Folding Cabinet Bed

In 1885, Sarah Goode became the first Black woman to receive a U.S. patent. Goode was born into descent-based slavery in 1850, and after the Civil War, she moved to Chicago and opened a furniture store.

There, she devised an idea that would bring more urban residents with limited space into her store: She invented a folding cabinet bed, which provided people living in tight housing accommodations the functionality of both a bed and a desk.

By day, the space-saving piece of furniture could be used as a desk, but at night, it could be folded out into a bed. The U.S. patent office granted Goode her patent 30 years before the creation of the Murphy bed, a hideaway bed that folds into a wall.

11. Potato Chips

No chef likes to hear that their work has been rejected, but George Crum was able to make magic out of one man's discontent. In 1853, Crum was working as a chef at a resort in Saratoga Springs, New York. A customer sent his dish of french fries back to the kitchen, claiming that they were too thick, too mushy and not salty enough.

Crum, in an irritated fit, cut the potatoes as thinly as possible, fried them until they were burnt crisps, and threw a generous handful of salt on top. He sent the plate out to the customer, hoping to teach the patron a thing or two about complaining. However, the customer loved the crisp chips, and soon the dish was one of the most popular things on the menu.

In 1860, when Crum opened up his own restaurant, every table received a bowl of chips. Crum never patented his invention, nor was he the one who bagged and sold them in grocery stores, but junk food lovers the world over still have him to thank for this crunchy treat.

10. Multiplex Telegraph

Imagine landing a plane without the help of air traffic controllers. These controllers advise pilots on how to navigate takeoffs and landings without colliding with other planes. Granville T. Woods invented the device that allowed train dispatchers to do the same thing in 1887.

Woods' invention, the multiplex telegraph, allowed dispatchers and engineers at various stations to communicate with moving trains via telegraph. Conductors could also communicate with their counterparts on other trains.

Before 1887, train collisions were a huge problem, but Woods' device helped make train travel much safer. Woods was sued by Thomas Edison who claimed he was the inventor of the multiplex telegraph, but Woods won that lawsuit. Eventually, Edison asked him to work at his Edison Electric Light Company, but Woods declined, preferring to remain independent.

He also received a patent for a steam boiler furnace for trains, as well as for an apparatus that combined the powers of the telephone and the telegraph.

9. Shoe Lasting Machine

When Jan Matzeliger was 21, he traveled to the United States from Suriname. Though he spoke no English, he landed a job as an apprentice at a shoe factory in Massachusetts.

At the time, the shoe industry was held captive by skilled craftsman known as hand lasters. They had the hardest and most technical job on the shoe assembly line: They had to fit shoe leather around a mold of a customer's foot and attach it to the sole of the shoe. A good hand laster could complete about 50 pairs of shoes a day.

Because the work was so skilled, hand lasters were paid very large salaries, which made shoes expensive to produce. To overcome the bottleneck, Matzeliger learned English, enabling him to study manufacturing. Using scraps, he invented a shoe lasting machine that produced 150 to 700 pairs daily. Although he died young from influenza, his invention made shoes more affordable.

8. Automatic Oil Cup

Even if you've never heard of the automatic oil cup, you've probably uttered the phrase that entered the lexicon because of it. The automatic oil cup was the invention of Elijah McCoy, who was born in 1843 to parents who had escaped slavery via the Underground Railroad.

McCoy was sent to Scotland for school, and he returned as a master mechanic and engineer. However, the job opportunities for a Black man — no matter how educated — were limited due to racial discrimination. The only work McCoy could find was with the Michigan Central Railroad.

McCoy's job was to walk along the trains that pulled into the station, oiling the moving parts by hand. McCoy realized that a person wasn't necessary for this job, and he invented the automatic oil cup, which would lubricate the train's axels and bearings while it was in motion. As a result, trains didn't have to stop as frequently, which reduced costs, saved time and improved safety.

The oil cup was a huge success, and imitators began producing knockoffs. However, savvy engineers knew that McCoy's cup was the best, so when purchasing the part, they'd ask for "the real McCoy."

7. Automatic Elevator Doors

Alexander Miles significantly impacted the safety of elevators with his groundbreaking design. Before Miles' innovation, passengers had to manually shut both the elevator doors and the elevator cage (a protective barrier that prevented accidental falls into the shaft). However, this manual method led to numerous accidents if individuals forgot to close the doors.

Recognizing the danger, Miles patented an automatic mechanism in 1887 that closed both the elevator doors and the elevator cage simultaneously when the elevator was in motion. His invention drastically increased elevator safety and is a foundational aspect of modern elevator design.

6. America's First Clock

Benjamin Banneker, a notable polymath, astounded his contemporaries by constructing a fully functioning clock entirely out of wooden parts in the 18th century. This mechanical marvel, which ran accurately for decades, showcased Banneker's exceptional engineering and craftsmanship skills.

Though he also engaged in pioneering research in other fields, like astronomy and the design of Washington D.C., the clock remains a standout testament to his innovative spirit.

5. Carbon-filament Light Bulb

Thomas Edison often gets the credit for inventing the light bulb, but in reality, dozens of inventors were working to perfect commercial lighting. One of those inventors was Lewis Latimer. In 1868, the Black inventor was hired at a law firm that specialized in patents in 1868; while there, he taught himself mechanical drawing and was promoted from office boy to draftsman.

In his time at the firm, he worked with Alexander Graham Bell on the plans for the telephone. Latimer then began his foray into the world of light.

At the time, Edison was working on a light bulb model with a paper filament (the filament is the thin fiber that the electric current heats to produce light). In Edison's experiments, the paper would burn down in 15 minutes or so, rendering the bulb unrealistic for practical use. It was Latimer who created a light bulb model that used a carbon filament, which lasted longer and made light bulb production cheaper.

Because of Latimer's innovation, more people could afford to light their homes. Latimer also received patents for a water closet on railroad cars and a predecessor to the modern air conditioner.

4. Walker Hair Care System

Sarah Breedlove Walker, born in 1867, faced a life filled with hardships from being orphaned at age 7, becoming a mother at 17 and widowed by 19. For years, she worked as a laundress. Later, facing hair loss — common among Black women of the time due to scalp ailments and damaging hair products — she claimed a dream revealed a unique pomade formula.

In reality, she served a stint as an agent for Annie Pope-Turnbo Malone, a Black woman with an established line of beauty products. Malone believed Walker (and others) knocked off her products.

Nonetheless, Walker continued to grow her empire. Using a pioneering direct sales approach, she trained women for door-to-door sales and even established a training university. Over her lifetime, she employed 40,000 people in the U.S., Central America and the Caribbean.

Contrary to popular belief, she didn't invent the hair straightening comb, but she did improve on the design (giving it wider teeth), which made sales soar.

Though often dubbed the first self-made woman millionaire, records place her worth at about $600,000 — a significant sum for her time. She generously supported institutions like the YMCA and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

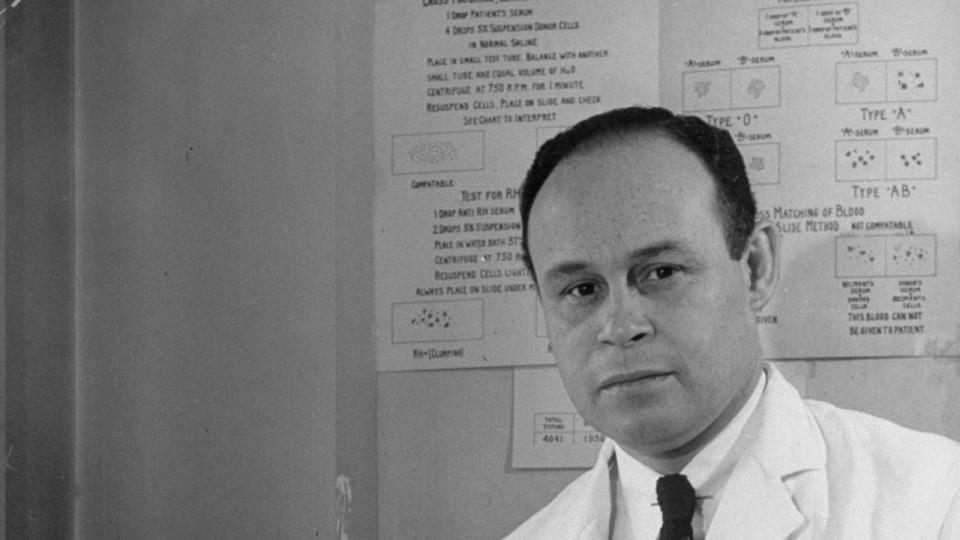

3. Blood Bank

Charles Richard Drew, with an M.D. and a Master of Surgery, pursued a Doctor of Medical Science degree at Columbia University in 1938. There, his interest in blood preservation led him to develop a method of separating red blood cells from plasma, extending blood storage beyond the then one-week limit.

The ability to store blood (or, as Drew called it, banking the blood) for longer periods of time meant that more people could receive transfusions. Drew documented these findings in a paper that led to the first blood bank.

Later, while overseeing blood preservation and delivery in World War II, he became the director of the inaugural American Red Cross Blood Bank for the U.S. Army and Navy, which served as the model for blood banks today.

However, Drew resigned his position because the armed forces insisted on separating blood by race and providing white soldiers with blood donated from white people, not African Americans. Drew knew that race made no difference in blood composition, and he felt that this move would cost too many lives. He returned to private life as a surgeon and medical professor at Howard University, where he worked until his death in 1950.

2. Protective Mailbox

Before 1891, dropping a letter in a U.S. public mailbox didn't guarantee its safety. The semi-open designs made mail vulnerable to theft and weather damage.

Philip B. Downing changed that when he invented a mailbox design with an outer and inner safety door. With the outer door open, the inner door shielded the mail; when closed, mail could be deposited. Thanks to his innovation, mailboxes became widespread, even in residential areas.

Born into a middle-class family in 1857, Downing had a long career as a clerk with the Custom House in Boston. He also received patents for a device to quickly moisten envelopes and one for operating street railway switches.

1. Gas Mask

Garrett Morgan only received a sixth-grade formal education, but he was observant and adept at learning. While working as a handyman in the early 20th century, Morgan taught himself the mechanics of sewing machines, leading him to start a business selling and repairing them.

Then, in his quest for a needle polish, he stumbled upon a formula that straightened human hair — marking his first invention.

Disturbed by the fatalities of firefighters due to smoke, Morgan devised the "safety hood," a precursor to the gas mask, which went over the head, featured tubes connected to wet sponges that filtered out smoke and provided fresh oxygen. This primitive gas mask became a sensation in 1916 when Morgan ran to the scene of a tunnel explosion and used his invention to save the lives of trapped workers.

In 1923, as automobiles were becoming more common, Morgan went on to develop an early prototype of the three-position traffic signal after seeing too many collisions.

This article was updated in conjunction with AI technology, then fact-checked and edited by a HowStuffWorks editor.

Lots More Information

Related Articles

Sources

Biography. "George Washington Carver Biography." (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.biography.com/articles/George-Washington-Carver-9240299

The Black Inventor Online Museum. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.Blackinventor.com/

California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. "Sarah E. Goode." (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.csupomona.edu/~plin/inventors/goode.html

Chan, Sewell. "About a Third-Rail Pioneer, Gallant Disagreement." New York Times. Dec. 26, 2004. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/26/nyregion/thecity/26rails.html

Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science. "Dr. Charles Drew." (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.cdrewu.edu/about-cdu/dr-charles-drew

Childress, Vincent. "Black Inventors." North Carolina A&T State University. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.ncat.edu/~childres/Blackinventorsposters.pdf

Dew, Charles B. "Stranger Than Fact." New York Times. April 7, 1996. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.nytimes.com/1996/04/07/books/stranger-than-fact.html

The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Case Western University. "Garrett A. Morgan." (Jan. 4, 2011)http://ech.cwru.edu/ech-cgi/article.pl?id=MGA

Famous Black Inventors Web site. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.Black-inventor.com/

Florida State University Research Foundation. "Dr. Charles Drew." (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.scienceu.fsu.edu/content/scienceyou/meetscience/drew.html

Fried, Joseph P. "A Campaign to Remember an Inventor." New York Times. Aug. 6, 1988. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.nytimes.com/1988/08/06/nyregion/a-campaign-to-remember-an-inventor.html

Fullam, Anne C. "New Stamp Honors Mme. C.J. Walker." New York Times. June 14, 1998. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.nytimes.com/1998/06/14/nyregion/new-stamp-honors-mme-c-j-walker.html

George, Luvenia. "Lewis Latimer: Renaissance Man." Smithsonian. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://invention.smithsonian.org/centerpieces/ilives/latimer/latimer.html

Geselowitz, Michael N. "African American Heritage in Engineering." Today's Engineer. February 2004. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.todaysengineer.org/2004/Feb/history.asp

IEEE Global History Network. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://ieeeghn.org/wiki/index.php/Special:Home

Indianapolis Star. "Madam C.J. Walker." Jan. 22, 2001. (Jan. 4, 2011) http://www2.indystar.com/library/factfiles/history/Black_history/walker_madame.html

Jefferson, Margo. "Worth More Than It Costs." New York Times. April 1, 2001. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/04/01/reviews/010401.01jeffert.html

Lienhard, John H. "Jan Matzeliger." University of Houston. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi522.htm

Louie, Elaine. "Inventor's House, Now a Landmark." New York Times. June 15, 1995. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.nytimes.com/1995/06/15/garden/currents-inventor-s-house-now-a-landmark.html

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Lemelson-MIT Program. Inventor of the Week Archive. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://web.mit.edu/invent/i-archive.html

National Inventors Hall of Fame Web site. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.invent.org/hall_of_fame/1_0_0_hall_of_fame.asp

New York Times. "An Inventor Who Kept Lights Burning." Jan. 29, 1995. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.nytimes.com/1995/01/29/nyregion/playing-in-the-neighborhood-jamaica-an-inventor-who-kept-lights-burning.html

Rozhon, Tracie. "A World of Elegance Built on a Hair Tonic." New York Times. Jan. 11, 2001. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0DE0DA113AF932A25752C0A9679C8B63&scp=6&sq=madame+c.j.+walker&st=cse&pagewanted=print

Schier, Helga. "George Washington Carver: Agricultural Innovator." ABDO. 2008. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://books.google.com/books?id=RDrFfbump4sC&dq=george+washington+carver,+peanut+butter&source=gbs_navlinks_s

United States Postal Service. "Five Fast Spring Clean Up Tips for Your Mailbox." May 18, 2009. (Jan. 4, 2011)http://www.usps.com/communications/newsroom/localnews/ct/2009/ct_2009_0518a.htm

Original article: 12 Black Inventors and Their Innovations That Shaped the World

Copyright © 2023 HowStuffWorks, a division of InfoSpace Holdings, LLC, a System1 Company