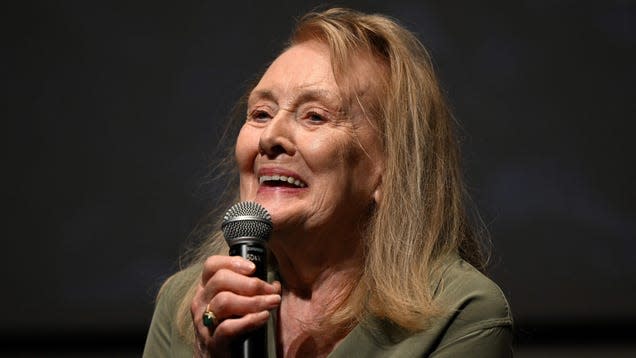

Annie Ernaux, winner of the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature, is a powerful voice in French feminism

This year’s Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to French author Annie Ernaux.

On Thursday (Oct. 6), the prestigious award went to the unconventional memoirist “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.”

Read more

While Ernaux was only recently recently discovered in the English-speaking world, she’s been making waves in her home country for decades. Her first book, Les Armoires Vides (Cleaned Out), published in 1974, was a fictionalised account of her own back-alley abortion in her early 20s that shed light on how working-class women had to resort to clandestine and perilous procedures in France’s judgmental society. Since then, she’s continued to write on controversial topics spanning class, gender, sexuality, race, and more. She returned to the topic of abortion in her 2000 novel L’événement (Happening), which was turned into a film and won the prestigious Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival in 2021.

At the time of the announcement, the Swedish Academy said it couldn’t “reach her on the phone” but said it looked forward to presenting the award to her in Stockholm in December.

This week, the Nobel Prize in Medicine went to Swedish geneticist Svante Pääbo, while quantum physicists Alain Aspect, John F. Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger bagged the honor in Physics, and the founders of click chemistry Carolyn Bertozzi, Barry Sharpless, and Morten Meldal won the Chemistry award.

The peace prize follows tomorrow, with economics closing the year’s series on Oct 10. All the announcements will be livestreamed.

Each winner will get a medal, a diploma, and 10 million Swedish krona ($901,608).

The Literature Prize, by the digits

117: Nobel Prizes in Literature awarded between 1901 and 2021

113: People who’ve been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature between 1901 and 2021

16: Women who won the Nobel Prize in Literature between 1901 and 2021

10: Times a candidate was awarded the prize when first nominated

0: Literature laureates who’ve won the Nobel Prize more than once

4: Only times the literature prize has been shared—a phenomenon that’s far more common in the other categories

17: Catalonian writer Angel Guimerà y Jorge holds the record for being nominated the maximum number of times—every year from 1907 until 1923—without winning

41: Age of the youngest literature prize laureate, Jungle Book author Rudyard Kipling. The Mumbai-born author is also the first English-language recipient of the prize

88: Age of the oldest Nobel Prize laureate in literature, British novelist Doris Lessing

9: The Nobel Prize, which typically recognizes a writer’s life’s work, singled out a specific work for particular recognition on these many occasions

Person of interest: Winston Churchill

In 1953, Winston Churchill, who served as UK’s prime minister twice between 1940 and 1945 and between 1951 and 1955, won the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values.”

Between 1945 and 1953, Churchill was nominated for the prize 21 times and twice for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1948, the Nobel Committee had even rejected Churchill’s candidature on the grounds that the prize “would acquire a political rather than literary import. A gesture of this kind could easily, in the light of Sweden’s justly or unjustly criticized stance during the Second World War, be misconstrued.”

He never won the peace prize.

Person who was not interested: Jean Paul Sartre

Jean Paul Sartre was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in1964 “for his work which, rich in ideas and filled with the spirit of freedom and the quest for truth, has exerted a far-reaching influence on our age.”

After reading a column in the Figaro littéraire that the choice of the Swedish Academy was tending towards him, Sartre penned a letter saying he would reject the prize were it offered to him. But it arrived after the committee had already settled on the French existentialist as the winner.

He clarified that it was not a rebuke of the Nobel Prize itself, but an alignment with his broader ideology of always refusing official honors in a bid to not be “institutionalized.” He had “personal and objective” reasons lining his decision.

Quotable

“A writer who adopts political, social, or literary positions must act only with the means that are his own—that is, the written word. All the honors he may receive expose his readers to a pressure I do not consider desirable. If I sign myself Jean-Paul Sartre it is not the same thing as if I sign myself Jean-Paul Sartre, Nobel Prize winner.

The writer must therefore refuse to let himself be transformed into an institution, even if this occurs under the most honorable circumstances, as in the present case.” —Sartre’s statement to the Swedish press in 1964

A Russian’s rejection

Besides Sartre, only one other person has turned down the literature accolade. Russian author Boris Pasternak returned the 1958 Nobel Prize after accepting it, more due to political pressures than free will.

When Pasternak won the Nobel prize, he sent the committee a telegram that read “Thankful, glad, proud, confused.” But once the Soviet Union threatened that he would never be allowed back into the Soviet Union if he traveled abroad to accept the prize, he declined it.

The author of Doctor Zhivago who was constantly at odds with the Soviet regime. His epic love saga set during the Russian revolution and WWII was rejected for publication in the Soviet Union in 1955 as it was seen as critical of the bolsheviks. However, luck put the manuscript in the hands of an Italian book publisher, who put it out in 1957. Protests against the book in the USSR only fanned its popularity, spurring more translations and sales. The CIA even purchased and distributed hundreds of copies to be used as a propaganda tool.

In 1988, Doctor Zhivago was finally published in the Soviet Union, and the following year Pasternak’s son was able to retrieve his father’s prize, which had remained in his name.

Money matters

Irish writer and playwright George Bernard Shaw, who won in 1926, accepted the prize but turned down the extravagant cash award. He then agreed to “momentarily” hold it, eventually donating it to creating English translations of Swedish literature.

For authors, the prize money ultimately doesn’t matter as much as the uptick in book sales post-award. Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz’s publisher had sold just 300 copies of his books in the three years prior to his Nobel prize win in 1988. After the prize announcement, 30,000 copies sold in just three minutes.

However, even an increased notoriety won’t shield winners from other obstacles, like the rise of book bans, something Nobel laureates Toni Morrison (The Bluest Eye) and William Golding (Lord of the Flies) posthumously know a thing or two about.

Related stories

👩🔬 The Nobel Prize committee explains why women win so few prizes

💡 The Nobel prize was created to make people forget its inventor’s past

📚 Book bans are spiking in the US. Here are the most targeted titles

Morgan Haefner contributed to this reporting.