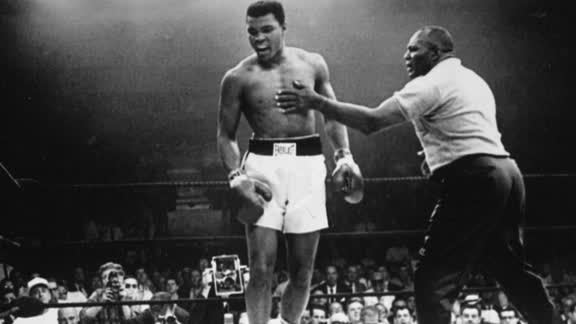

Boxing: Why Muhammad Ali was different to everyone else

Yahoo UK's Adam Powley explains why Muhammad Ali had even the most cynical sports journalists starstruck when they met him

Sports journalists tend to be a pretty cynical bunch, and as a species are not easy to impress. When a routine part of the job is to rub shoulders with the famous and examine their performances and lives, warts and all, it inevitably means the stars of global sport don’t usually render hard-bitten hacks starstruck.

There are exceptions. A few years ago I was in the company of a number of writers from a variety of disciplines, chewing the fat and telling old war stories about who they have met on their professional travels. There were a series of tales about the great and the good, and the not so good, that made for interesting, amusing, but hardly earth-shattering listening. That was until one among the number told of how he had met Muhammad Ali.

From his wallet the writer produced the great man’s autograph - a fading signature on a scrap of ragged old paper, evidently sourced some time ago and cherished with great affection. We gathered around and looked at it with wide-eyed wonder like some rare and precious artefact. We were starstruck.

It is telling that in the aftermath of Ali’s death, so many people have told similar stories of how they met Ali, talked to him, had a picture taken with him, got his autograph. In truth his signature is probably not an especially rare thing. Far from being a hideaway superstar aloof from his worldwide fanbase, it seemed Ali would stop and talk to anybody and everybody. He must have met and personally conversed with tens of thousands.

The insistence from those with first-hand memories of Ali that he wanted to meet and communicate with them stands as testimony to his inclusivity. He might have been The Greatest, but that didn’t stop him from being the greatest communicator.

Ali, of course, put it best himself. He said that one of the things he wanted to be remembered for was ‘as a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him’. This might seem a paradox, given his obvious satisfaction with the superiority of his boxing skills, his looks and just about everything else. But much of it was delivered with a wit and a knowing wink to let us know we were all in on the joke.

He wasn’t always funny. Ali was not a saint. He was a very mortal, very human individual with flaws, carrying the rough edges and imperfections that make a rounded human being as much as their finer qualities. The best boxing scribes - and the fight game has long produced some of the finest chroniclers of any sport - made it clear that there were justified criticisms of how badly Ali treated some people, particularly fellow fighters and those closest to him.

Neither was he universally popular. The reaction to his draft refusal to fight in Vietnam and the withdrawal of his boxing licence was received with vicious glee by many in America and beyond. The prejudice and racism Ali suffered was explicit.

There are still people of a certain generation who call him Cassius Clay, the name he rejected as an inheritance of slavery. My dad was of that age group, but not among their number. Like millions more, he admired Ali for his boxing talent, his supreme entertainment value, and for his courage in standing up for what he believed in. Refusing the draft and sacrificing his peak years as a boxer were actions that demanded respect.

Even in Britain, in which it was often said Ali was made to feel more welcome and appreciated than in his country of birth, there were many who took great offence at Ali’s braggadocio, and reacted with spiteful relish in seeing him suffer. His critics did not take kindly to an individual expressing himself with such supreme self-regard - no one really likes a big head, after all. But the reality is too many people took exception not to what Ali said but simply because Ali was black and said it.

The loss of those prime years contributed to Ali’s later demise, compelling him to fight on when he really should have been calling it quits and with his razor-sharp mental faculties intact. We all rightly champion the epic contests between Ali and a bevy of brilliant contemporaries, but the ring wars with the likes of Ken Norton, George Foreman and, most infamously, Joe Frazier, took their obvious toll. The Thriller in Manila is still one of the most exciting and compelling spectacles in all of sporting history, but watching it now, knowing with hindsight that it nearly cost both fighters their lives, is one for individual consciences.

This battle and the subsequent beatings Ali continued to take almost into his 40s, condemned him to a life of physical suffering. It seems abundantly clear that the long years of ring damage caused Ali’s Parkinson’s Disease. It was a condition my own father had in later life. Ali still outlived my dad and many of his own generation, which is a remarkable fact in itself. Many of the obituaries and tributes that had been prepared years in advance had to wait a while longer to be released than anticipated, such was Ali’s enduring strength and spirit.

The homilies rightly pointed out that he transcended sport. Perhaps he was the emblematic figure of the modern, globalised age of sport, media, politics, society and much more. The brilliant series of TV interviews with Michael Parkinson, fights of verbal swordplay in which Ali became genuinely angry, were vivid illustrations of how he could deliver punchlines in and out of the ring on a whole range of issues.

It feels odd as well as sad to write about him in the past tense. The Ali family have invited ‘the world’ to his funeral on Friday. That post-Ali world, the one he said he had shaken up in the aftermath of his defeat of Sonny Liston, is going to take some getting used to. It is a poorer, less interesting one for his passing, but a surely a better one for his legacy.