Business as usual on German border as EU seeks migrants deal

By Jörn Poltz

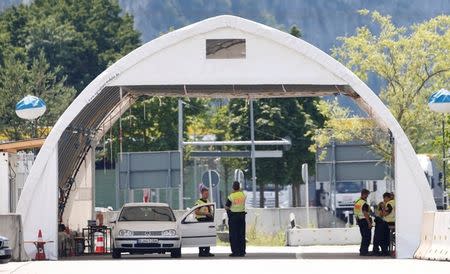

KIEFERSFELDEN, Germany (Reuters) - Near the quiet Bavarian village of Kiefersfelden, cars and trucks can be seen waiting in long lines to cross the border between Austria and Germany.

Under the Alps, police conduct random searches of vehicles before waving them on. These days, there are few stowaways.

It's a far cry from three years ago. At the height of the civil war in Syria, Chancellor Angela Merkel threw Germany's doors wide open and thousands of migrants and asylum seekers entered the country each day through the rich state of Bavaria.

But the doors could be about to slam shut again if European Union leaders fail to settle differences over the bloc's system for taking in migrants at a summit in Brussels on Thursday and Friday.

If there is no deal, Bavaria's Christian Social Union (CSU), which is part of Merkel's coalition government, has threatened to start refusing entry at the border to migrants who have already registered elsewhere in the bloc.

Permanent controls could be reinstated at a border that has not had them for decades because Austria and Germany are in Europe's visa-free Schengen area -- the creation of which is seen by many Europeans as the EU achievement that, along with the euro currency, affects their lives most.

The number of illegal entries is tiny compared to the thousands who enter legally each day. Critics say tightening controls would be largely symbolic but could have far-reaching political consequences, possibly braking up the coalition.

"It's absolute nonsense," said architect Andreas Hausbacher, whose quickest route from his home in the Austrian town of Kufstein to the building site where he works in the Austrian city of Salzburg is through Germany.

Hajo Gruber, Kiefersfelden's mayor, acknowledges the changes would be mainly symbolic but adds: "Merkel is right when she says the problem has to be solved on a European level. Anything else would be crazy."

EU UNITY UNDERMINED

With populist, right-wing and anti-establishment parties on the rise in several EU countries, disputes over immigration are undermining unity in a bloc whose future is also clouded by the decision of one of its biggest members, Britain, to leave.

The outcome of the Brussels summit is vital for the EU's unity and the future of Merkel, who has been in power since 2005 and is the EU's longest-serving and most powerful leader.

Merkel, whose rich country is the most popular destination for migrants and Europe's biggest economy, is under pressure from the CSU to win greater powers for member states to turn away those who have registered in another EU state.

Leaders of the Mediterranean countries where most migrants enter the EU and register say that is unfair and want the burden for taking them in spread among member states.

Resistance has been led by Italy's new anti-establishment government which is bent on overhauling European EU budgets and immigration policy.

Italy has started turning away ships with migrants rescued at sea and wants to drop rules stipulating that the first EU country of arrival is responsible for any given person.

Rome wants "international protection centres" created to screen asylum requests in transit countries such as Libya. It has suggested countries that refuse to take in new arrivals should receive less EU money -- a proposal opposed by the ex-Communist states of Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic which do not want more migrants.

No breakthrough was found at an emergency meeting of 16 EU states on Sunday. A solution looks even less likely when all 28 national states meet in Brussels.

"To be honest, it looks very difficult to reach a solution at this European Council (EU summit)," Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Lofven said last week.

Underlining the pressure European governments face over immigration, Swedish right-wing leader Jimmie Akesson, who party is benefiting from an anti-immigration backlash, reminded Lofven that immigration "remains the most important issue for voters."

The divisions over immigration have also affected other areas of cooperation, including talks on the bloc's seven-year budget from 2021.

SEPARATE DEAL

Merkel said on Sunday she would seek deals on migration with separate EU states as she could "not always wait for all 28 members". But a spokesman said on Monday she sill hoped for agreement on a European level.

Agreement at the summit is expected to be limited to a deal to spend more money on Syrian refugees who reach Turkey and setting up centres outside the EU to decide on asylum requests and send back those whose cases fail.

The CSU, which faces a challenge from the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AfD) party in elections in Bavaria in October, will meet on July 1 to decide its next steps.

Turning back migrants would mean rigid border controls inside Schengen and have a knock-on effect on other EU states, hitting cross-border business and travel. If borders inside the Schengen area are reinstated, it would be seen as a big setback in many EU states.

An opinion poll published in Germany on Sunday showed the dispute was weakening support for Merkel's coalition and pushed the anti-immigration the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany (AfD) party to its highest ratings.

(Additional reporting by Thomas Escritt in Berlin, Gabriela Baczynska in Brussels, Simon Johnson in Stockholm and Crispian Balmer in Rome, Editing by Timothy Heritage)