Celebrated WW I tunneller from N.S. to be honoured in new exhibit

Nova Scotia's Sam Glode played a role in crucial moments of the First World War, including the battles of Messines and Vimy Ridge.

Now his family will get to commemorate his accomplishments at a ceremony planned for later this year, according to his great-great-grandson.

Jeff Purdy and other family members plan to be at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Que., for the launch of an exhibition featuring Glode, a Mi'kmaw man from Milton in Queens County.

An official date for the launch has not been announced, according to a spokesperson for the museum.

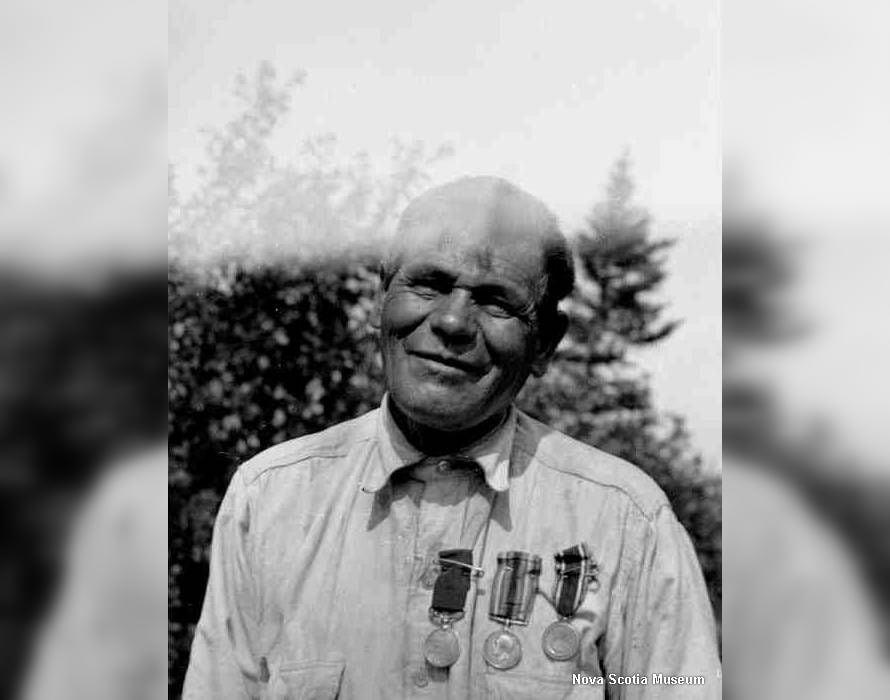

Glode was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for bravery in 1918, one of the highest honours awarded to an Indigenous veteran from the war.

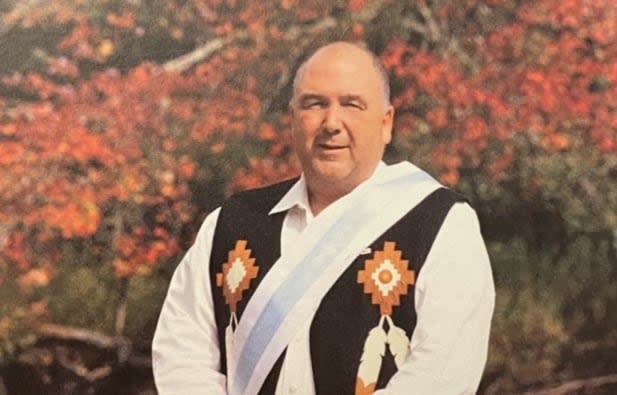

Jeff Purdy is the great-great-grandson of Samuel Glode. (Chelsey Purdy)

Purdy said he remembers his mother and grandmother speaking of Glode's achievements. "I named my son after Sam Glode," he said.

"We're very fortunate to be his offspring. Sam's name is brought up a lot, and we're always very honoured and proud to say that we're his family."

Glode died in 1957 at the age of 79.

In 1917, Glode was part of the Royal Canadian Engineers No. 1 Canadian Tunnelling Company. Many of them were miners from Cape Breton.

Jeff Purdy's son, Sam, is named after his great-great-great-grandfather (Chelsey Purdy)

The tunnellers — or sappers — helped plant explosives deep under German lines at Messines Ridge, near Ypres, Belgium.

June 7 detonation

The mines were detonated early in the morning of June 7, resulting in one of the largest man-made explosions at that time.

It allowed the Allies to push forward and damaged German morale.

Glode, a hunter and guide, was working as a lumberjack in Milton in 1915.

In a 1944 interview with Thomas H. Raddall published in Cape Breton's Magazine in 1983, Glode said he and an Indigenous friend, John Francis, had just felled a tree when his friend suggested they join the army.

According to Glode, Francis said the army was paying $1.10 a day and offered free food and clothing. They both quit and went to Liverpool, N.S., to enlist.

Glode, 35 at the time, sailed to England with his regiment in 1916.

While at a training camp there, Steve Battersby, who had been a coal miner in Cape Breton, suggested they volunteer for the Canadian Engineers, who were looking for miners.

"I told Steve, 'I'm not a miner,' Glode said in the interview. Battersby replied 'Shut up. You want to see France don't you?'"

A destroyed German trench on Messines Ridge in 1917. (John Warwick Brooke/ Imperial War Museum Q 2325)

Brian Pascas has written about the work of the tunnellers.

Unbearable conditions

He said men in the tunnels faced almost unbearable conditions.

He said the men had to hunch low in the tunnels. There was the constant threat of poisonous gas and collapsing walls.

In his interview, Glode said Canadian sappers dug for a year to complete the tunnels by early summer 1917.

He said at one point he was caught in a tunnel collapse with 20 other men. They were digging under no man's land.

There were 25 explosive caches planted under the ridge containing almost half a million kilograms of explosives.

British soldiers stand looking into the huge crater at Messines Ridge. (Imperial War Museum/ IWM (Q 2325))

At zero hour on the morning of June 7, Glode and other Canadian tunnellers were watching the Messines Ridge from a nearby hill when 19 of the 25 mines planted were detonated.

He said there was a thud and they felt the ground shiver. Some estimates of the number of Germans killed range from 2,700 to 10,000.

The mud and barbed wire of Passchendaele in 1917. (William Rider-Rider / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-002165)

Passchendaele and Vimy Ridge

After Messines, Glode went on to Passchendaele and Vimy Ridge.

At Passchendaele, he witnessed the conditions faced by so many other Canadian soldiers.

"I never saw such a mess," he said. "You couldn't dig anything deep around there because the ground was all mud and water."

Glode returned to Nova Scotia in early 1919 and returned to the simple life he knew and loved.

He lived in a shack near Milton and continued to work as a hunter and guide.

"I joined the Canadian Legion at Liverpool and used to go down there a lot, talking to other veterans over a few drinks of beer or rum," he told Raddall.

MORE TOP STORIES