COP28: 5 big takeaways on a historic climate agreement

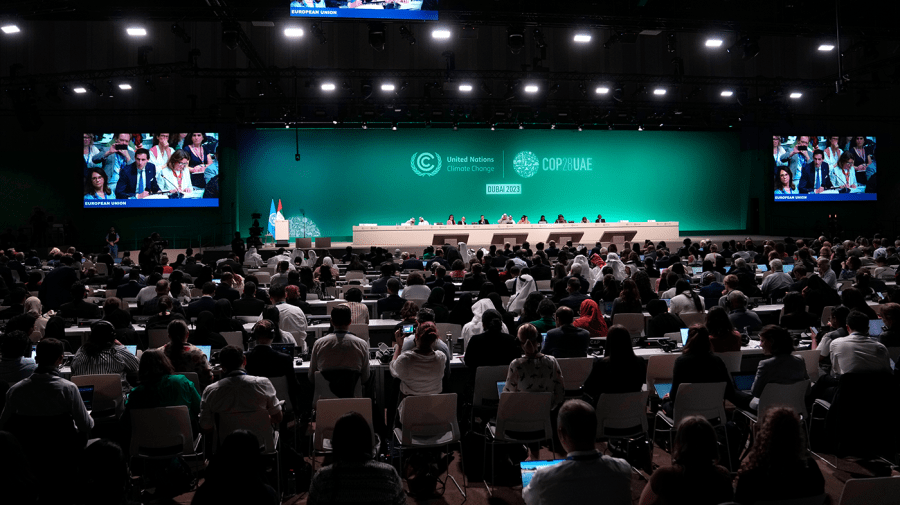

The roller coaster of this year’s United Nations Climate Conference (COP28) has ended with a historic new agreement: For the first time, world governments have said countries should transition away from fossil fuels.

The deal comes after days of tense negotiations, especially over the fossil fuel language, which caused the Dubai conference to stretch into overtime.

Climate advocates have praised it as a step forward, but also raised concerns about potential loopholes in its language and criticized it for not going further as the climate crisis deepens — and fossil fuel production continues to increase.

Here are five takeaways from the decision reached Wednesday:

Nations commit to transitioning from fossil fuels

The nearly 200 countries that are parties to the agreement approved language calling for “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems.”

This is significantly stronger than language used in past years’ decisions, which simply called for reducing the use of coal whose emissions are not captured and did not call for reductions in oil and gas at all.

“The message coming out of this COP is: We are moving away from fossil fuels. We’re not turning back,” U.S. climate envoy John Kerry told reporters.

This outcome was hard fought. Many nations were calling for a “phase out” — or eventual elimination — of fossil fuels, but others preferred to simply reduce the use of the planet-heating fuels.

Ultimately the language they landed on is ambiguous — it’s not totally clear whether a “transition away” means moving away from the fuels entirely or just partially.

Member states were clearer on what they were transitioning toward: They agreed to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030 — a move the International Energy Agency (IEA) says is vital to secure a safe climate — and to double energy efficiency.

For 30 years, global climate negotiations have never been forced to confront “that fossil fuels were the cause of the climate emergency,” said Jean Su, energy justice director at the Center for Biological Diversity.

The “big process win” of COP28 is that negotiators finally have a deal “that signals that the fossil fuel era at some point has to end,” she added.

Island nations, developing countries and climate activists say it’s not enough

Island nations, developing countries and climate activists all expressed dissatisfaction with the decision.

Anne Rasmussen, the delegate from Samoa, part of a group of small island nations that are particularly vulnerable to climate change, called the decision an ‘incremental advancement over business as usual” but said what is needed is “exponential change.”

She lamented that there was no call to peak emissions by 2025, which small island countries see as vital to protect their nations from being swamped by rising seas.

She also said that a group of island nations were literally not even in the room when the decision was adopted.

“We are a little confused about what happened. It seems that you just gaveled the decisions and the small island developing states were not in the room,” Rasmussen said during a COP meeting.

“We were working hard to coordinate the 39 small island … states that are disproportionately affected by climate change and so we were delayed in arriving here.”

Some additional criticism stemmed from the failure to secure an explicit commitment to eliminate fossil fuels — as opposed to just moving away from them — as well as what advocates see as loopholes in the text.

Su pointed to the language applying the call to transition away from fossil fuels particularly to “energy systems,” leaving other uses open.

“That allows for plastics and other non-energy forms of fossil fuels to still proliferate,” she said.

She also pointed to language in the decision that “recognizes that transitional fuels can play a role in facilitating the energy transition” — noting that many countries consider natural gas to fall under this category.

Natural gas is a fossil fuel that releases planet-warming greenhouse gasses when burned. It is less carbon-intensive than oil and coal, though additional emissions that come from its production and processing may cancel those benefits out, according to a study published in the journal Science.

The support for gas — and the lack of explicit financial support for developing countries in the agreement — is a particularly hard blow for African countries, many of which were in favor of a fossil fuel phaseout but can’t get there without significant upfront investment, Collin Rees of Oil Change International said.

While renewables like wind and solar cost less than gas overall — even when the cost of climate change isn’t factored in — that money has to be paid up front, while countries can buy gas tanker by tanker.

In sum, the deal “reflects the very lowest possible ambition that we could accept rather than what we know, according to the best available science, is necessary to urgently address the climate crisis,” said Madeleine Diouf, climate minister of Senegal.

Because the rule is not binding, questions surround action

While the text calls for a transition away from fossil fuels, the agreement relies on member governments to take concrete action to meet it — and it remains an open question how much action they will actually take.

Nathan Hultman, who previously worked on international climate issues for the Biden administration, acknowledged that the responsibility now lies with national governments.

“Ultimately, it’s going be up to countries to make the policy decisions,” he said. But he called the international process a “critical part” of moving action forward.

Hultman pointed to the Paris Agreement — under which countries agreed to try to keep the average global temperature increase to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) — saying that the similarly tough-to-enforce 2015 agreement “substantially accelerated action across the world.”

Others were more skeptical.

Morgan Bazilian, who attended the conference as part of the Irish delegation, told The Hill he doesn’t think countries will “make large investment or policy or regulatory decisions because of that language” calling for a transition away from fossil fuels.

One particular concern point was the failure to agree to end subsidies for fossil fuels, even as negotiators identified the fuels as the principal source of the chemicals warming the planet.

In 2022, the sixth-hottest year on record, world governments for the first time spent more than $1 trillion on subsidies to the fossil fuel industry, according to the IEA.

In the ultimate deal, member nations agreed to phase out “inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that do not address energy poverty or just transitions, as soon as possible” — terms that experts say leave vast wiggle room for subsidies to remain.

This language “essentially singles out only a subset of ‘inefficient’ subsidies, which has no agreed definition anyway. Basically everyone always just determines that all of their own subsidies are efficient — so no need to do anything,” Rees of Oil Change International said.

Rees noted that language around subsidies was “stronger in earlier drafts over the last two weeks,” arguing that the influence of the more than 2,400 fossil fuel lobbyists who were given access to this year’s conference — a record number — “was very clear.”

Deal calls for limiting warming as world heads toward dangerous threshold

Ahead of COP28, the U.N. released a report finding that the world was on track to warm by an average of about 2.9 degrees Celsius (5.2 degrees Fahrenheit) — nearly double the goal that climate scientists believe would prevent the worst effects of climate change.

At the summit, global leaders were tasked with taking stock of their progress and looking to do more.

The final text notes that limiting warming to 1.5 degrees “requires deep, rapid and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions” including cutting emissions 43 percent by 2030 and 60 percent by 2035 compared to 2019 levels.

It also calls on countries to contribute to global efforts including the transition away from fossil fuels, a reduction in coal whose emissions are not mitigated through carbon capture, reducing methane emissions by 2030, and tripling renewables and doubling energy efficiency.

Hultman, who is now the director of the University of Maryland’s Center for Global Sustainability, said that the ultimate decision text provides a “good set of guiding ideas” as countries work on their 2035 climate targets.

“Having this global conversation is part of the overall guidance that countries can be thinking about and they will be now trying to better understand their pathways to higher ambition in the 2035 period,” he said.

Challenges loom for the US

While the U.S. has passed significant climate legislation and taken regulatory actions to limit greenhouse gasses under the Biden administration, the goals set by the agreement could mean even more work to do.

President Biden, in a written statement, celebrated the agreement, and particularly its call for a transition away from fossil fuels, as a “historic milestone.”

“While there is still substantial work ahead of us to keep the 1.5 degree C goal within reach, today’s outcome puts us one significant step closer,” he said in a written statement.

Kerry, the U.S. climate envoy, praised the U.S. for “leading the charge on the home front” through the Biden administration’s signature 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The IRA is a major climate bill with significant subsidies for renewables that was only supported by Democrats. He also pointed toward billions of dollars of U.S. funding to cut emissions and boost clean energy at home and abroad.

Yet many hurdles still remain for getting more renewables onto the U.S. grid.

And while the country has taken steps aimed at reducing its own reliance on fossil fuels, drilling in the U.S. is currently at an all-time high, and it has made decisions that are expected to expand the use of the fuels globally.

Under the COP process, however, progress on national climate targets is focused on emissions that directly occur in a certain country — rather than those that come from oil produced in one country and used in another.

Because of this, Hultman said, “there’s not an inherent conflict between us having deep emissions reduction goals in the US and achieving them” while continuing to produce oil and gas for export.

But he said that ultimately the nation would have to specifically address its own oil and gas production.

One specific wrinkle in doing so, however, is the peculiar structure of the U.S. oil and gas industry, which is dominated by private companies choosing whether or not to drill on privately owned lands.

That separates the U.S. from countries like Russia, Brazil or the United Arab Emirates where publicly owned oil companies control the industry.

“It’s not like the national oil companies in other countries are going to be running to [move off fossil fuels] either,” Bazilian of the Colorado School of Mines told The Hill.

But in the U.S. oil patch specifically, he said, “the nature of the distributed decision making process makes this extremely difficult,” and the way the language around the transition away from fossil fuels would play out in the U.S. “is highly unclear.”

“I think it will largely be ignored,” Bazilian added.

But many of these questions may become moot if Republicans win control in 2024.

While a handful of Republican congressional members went to Dubai to participate in the climate conference, the party as a whole has been hostile to the COP process — and to the broader goal of moving off fossil fuels.

Republicans have also repeatedly attempted to strip green energy tax credits and pass resolutions repealing climate regulations.

House Resolution 1, the GOP’s signature energy package, would zero out the Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, a “green bank” aimed at promoting clean energy, as well as fees on fossil fuel companies’ release of methane, a planet-warming chemical dozens of times more potent than carbon dioxide.

And while the climate solutions Republicans promoted at the summit have some overlap with Democrats’ plans to scale up clean energy supply chains, they also rely heavily on nuclear and natural gas.

Meanwhile, former President Trump, who is currently the front-runner for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination and who pulled the U.S. out of the 2015 Paris Agreement during his time in the White House, has been telling crowds that he would be “a dictator” on “day one” of his presidency, at which point he promised to use his executive power to promote “drilling, drilling, drilling” for fossil fuels.

But Kerry noted that — even with Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement factored in — the world was still making vital progress.

At the time of the 2015 deal — which he attended as then-President Obama’s secretary of State — “the world was headed toward as much as 4 degrees [Celsius] of warming,” Kerry said.

“So it is a privilege to be here, eight years later … with nations around the world committed to taking the actions necessary to keep 1.5 C alive.”

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to The Hill.