How data is helping elite athletes beat the smog

As the issue of air pollution continues to grow, athletes are turning to science to give them a clearer picture of how to avoid the smog.

Air quality sensors have been installed in sports facilities in six countries across Africa, with the data being used by coaches drawing up training schedules and event organisers looking to keep competitors safe.

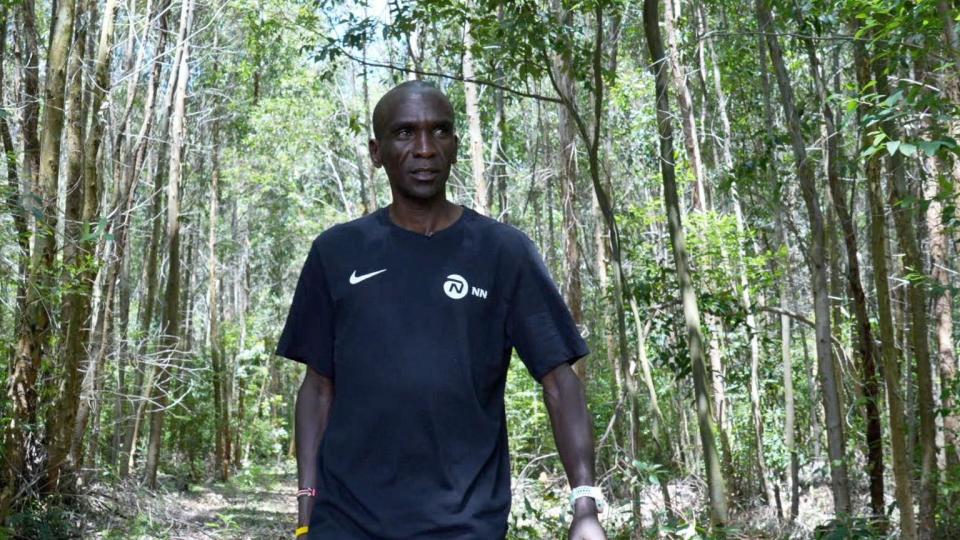

“If you run in a polluted city you can decrease your performance,” two-time Olympic marathon champion Eliud Kipchoge told BBC Sport Africa.

“When you go to a polluted city, you really feel that your lungs are really compressed.”

Air pollution causes more than 1.2 million deaths annually in Africa, according to the United Nations and the Clean Air Fund, making it the second-largest cause of death across the continent.

The situation is particularly worrying for those who train regularly, because someone exercising can take in as much as 20 times more air than a person at rest – meaning they also breath in 20 times more pollutants.

Badly polluted environments can therefore make all the difference for elite athletes looking for crucial marginal gains.

For example, one study by the United States National Library of Medicine found that air pollution can decrease marathon performance by 1.4%.

“If you were to run that long period of time in an environment where there's polluted air, you cannot sustain it,” said Dr Philip Osano of the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), the organisation which has installed the sensors in conjunction with United Nation’s Environment Programme (UNEP).

“It really affects your breathing capacity and your blood oxygen levels.”

Training centres in danger

The sensors have been installed in stadiums and training centres in Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Senegal, Tanzania and Zambia.

The Kenyan town of Iten, where runners from around the world base themselves, is one of those locations, with researchers particularly focused on the levels of fine particulate matter, a pollutant invisible to the naked eye.

Kipchoge says Iten has “really changed” over the past 20 years, including an increase in the number of cars which, on African roads, are often older, use more fuel and have higher emissions.

“Many tracks have been tarmacked,” explained the 39-year-old, a keen environmental campaigner who maintains his own forest.

“Where I'm training is near the forest, where the oxygen is clean. I’m trying to conserve the forest. I plant a lot of trees.”

Maxwell Nyamu, the head of a sustainability programme at Athletics Kenya (AK), describes the deterioration of the environment in Iten as a “threat to the sport and communities”.

“The forest cover has reduced and pollution has increased,” Nyamu told BBC Sport Africa.

“The forest was supporting [us] in terms of absorbing the extra carbon that cars emit.”

Making changes

So far, the data has largely been used to help runners and their coaches adapt their training – with readings showing increased levels of particulate matter in the morning and also sometimes late evening.

But avoiding the pollution entirely can prove difficult.

In January of this year eight full days were deemed “unhealthy” for those training at Lobo Village in Eldoret, another elite training site near Iten.

“Our training areas where we have a lot of athletes are really going to be in danger if we don't do something about it,” AK president Jack Tuwei said.

“This is a major issue.”

Upon receiving adverse readings, AK shares the data with a technical team, who then pass it on to coaches.

“On more than one occasion we've been changing location and the timing (of training),” said Bernard Ouma, an athletics coach and environmental scholar.

“Where we were supposed to start by 8am, we ended up starting by 10am. Where we were supposed to be in Nyayo (Stadium), we ended up going to Karen [another training centre in Nairobi].

“The logistics can be a bit tedious changing locations, but, after all, [it is] for the safety of the athletes.”

Improving air quality

The data has also proved crucial in organising big events.

Last year, a marathon in Nairobi was almost cancelled because of adverse readings from the sensors.

But organisers were able to work out that stationary cars were the cause and make amendments to improve air quality.

“This data was able to help us divert traffic,” Nyamu said, revealing that his team worked with local authorities as well as the police service and its traffic department.

A report by IQ Air gave the town of Benoni, just east of Johannesburg in South Africa, the dubious distinction of having the most polluted air in Africa while other major cities on the continent, including Bloemfontein, Ouagadougou, Abuja, Cairo and Kinshasa, are not far behind because of increasing urbanisation and industrial activity.

The UNEP is aiming to improve its data collection by installing more monitors.

“The plan is to be able to tell people, with a degree of certainty and precision, the quality of air we are breathing - but most importantly how to ameliorate that and come up with better air quality across the continent,” Dr Rose Mwebaza, the UNEP’s regional director for Africa told BBC Sport Africa.

The data provided so far has been invaluable to those fighting for a spot in Kenya’s team for this year’s Paris Olympics.

“It is easier to win an Olympic gold medal than making the Kenya team,” Ouma said.

“It is so tight that missing a training program has a huge effect. But since we have the data [it] is easier to manage.”

Organisers are promising “the greenest” and “most sustainable” Olympics in Paris, promising to halve the event’s carbon footprint compared to the average of previous Games.

As athletics leads the campaign to highlight air quality issues in Africa, it is hoped the data from the current project could be used to improve safety at the continent’s upcoming major events as Senegal prepare to host the 2026 Youth Olympics and East Africa gets ready for the 2027 Africa Cup of Nations.