Dementia frontrunner Japan destigmatises condition, stresses community care

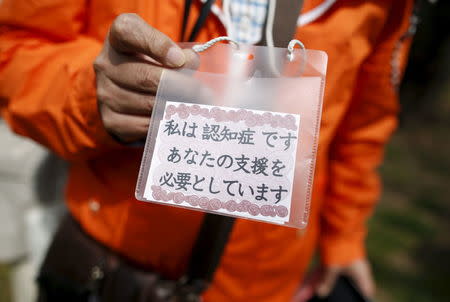

By Linda Sieg and Kwiyeon Ha TOKYO (Reuters) - When Masahiko Sato was diagnosed at age 51 with early-onset Alzheimer's, he felt his life was over. A decade later, Sato has a mission: destigmatising a condition with a growing social impact in a country that leads the global ageing trend. "What I want most to tell people is, 'Don't underestimate your abilities. There are things you cannot do but there are lots of things you can do, so do not despair," Sato told Reuters in an interview at a park outside Tokyo, where he and his supporters gathered for traditional cherry blossom viewing. "The most painful thing is when someone says 'I am pitiable'. I am not pitiable. There are inconveniences, but I am not unhappy," said Sato, a former systems engineer who has lectured around Japan and written a book with the same message. Encouraging people with dementia to speak out is part of Japan's effort to ease the negative image of a disorder that affects nearly 5 million citizens and is forecast to affect 7 million, or one in five Japanese age 65 or over, by 2025. Japan is a global frontrunner in confronting dementia, the cost of which has been put at 1 percent of world GDP. "Whether people with dementia can 'come out' depends on the values and culture of the community," said Kumiko Nagata, research director at the Dementia Care Research and Training Centre, Tokyo, adding that attitudes were changing. To be sure, people with dementia like Sato, a bachelor who managed to live alone until last year by using his phone and now an iPad to make up for memory loss, are a minority. Many live with relatives who struggle to juggle care with jobs. Some 100,000 workers quit each year to care for elderly relatives, a figure Prime Minister Shinzo Abe aims to cut to zero by 2025, when all Japan's babyboomers will be 75 or older. Families providing care accounted for nearly half of the estimated 14.5 trillion yen ($133 billion) in social cost of dementia in Japan in 2014. Kanemasa Ito is one such care-giver. Ito had to shut the two convenience stores he and his wife, Kimiko, ran together when she was diagnosed with dementia 11 years ago at the age of 57. "I had planned to work until I was 85," Ito told Reuters, sitting with Kumiko at their home in Kawasaki, south of Tokyo. "I thought, will the rest of my life just be caring for my wife?" added Ito, 72, who later became a home helper himself and now entrusts his wife to a day-care centre several times a week. 'INCREASE UNDERSTANDING' To keep Kimiko from wandering off, he installed a special bolt on the front door and makes sure she wears a GPS tracking necklace when they go out in case she slips away. Nearly 11,000 people with dementia were reported missing, most temporarily, in 2014. Others are abused or even killed by relatives. Policy-makers and experts hope the positive message will help achieve a goal of dementia-friendly communities where elderly can stay at home or in small group homes rather than in large, costly institutions that can aggravate their condition. "There has been a tendency to view dementia as a disease of which to be ashamed," Tadayuki Mizutani, head of the health ministry's dementia policy promotion office, told Reuters. "We have been campaigning to increase understanding of dementia. What is new is to have people with dementia speak out in their own words." That was an element in government proposals unveiled last year for improved dementia care that include a stress on early detection, more doctors and primary care-givers to look after those with dementia, "SOS networks" of police, residents and businesses to find missing people and volunteer "Dementia Supporters" trained to help people in the community. The government has budgeted 22.5 billion yen for the plan in the year from April 2016, up from 16.1 billion last year. Experts give Japan high marks for its community-oriented programs as well as its efforts to destigmatise the disease. "The focus in Japan is on care - what do you do for people with dementia living in the community?" said John Campbell, a University of Michigan professor emeritus. Still, some worry that reforms of Japan's Long-term Care Insurance system, under fiscal pressure in a country with huge public debt, are boosting families' burdens by making it harder for those with lighter disabilities to access services. For Kanemasa Ito, any cutbacks could threaten his dream of caring for Kumiko at home. "I want to live with her at home as long as possible," he said, gently touching her wrist. (Reporting by Linda Sieg; Editing by Robert Birsel)