What does the booming sperm-donor industry owe to people it helps conceive?

Trying to decide on a sperm donor means sorting through a dizzying amount of information.

Log onto the site of California Cryobank, one of the largest sperm banks in the US, and you can scroll through hundreds of detailed profiles of men whose genetic material could be used to conceive your future children.

Read more

Donors can be sorted by factors ranging from ethnic background to their height or college majors; flipping through their childhood photos allows you to scout for traits like curly hair or dimples. You also get insights into their personalities. In brief personal essays, donors reflect on how their values were shaped by living abroad in Spain or weekend camping trips with a beloved grandparent.

Then there’s the really serious stuff: pages of donors’ genetic testing results and medical histories, which reveal whether their descendants might be prone to anything from cystic fibrosis to heart disease or anxiety.

But no matter how much information prospective parents have about a donor, it may not be sufficient. The donor could turn out to have a genetic condition that hadn’t yet manifested when they shared their sperm at the age of 23—one that could be passed down to offspring who have no idea they might be vulnerable. People conceived via donors might have pressing questions about their backgrounds as they age, or want to meet up with half-siblings who share the same donor. And there’s always the possibility that donors’ information may be inaccurate: There’s no federal law requiring gamete banks to verify donors’ statements about their backgrounds and medical histories.

A new Colorado law—the first of its kind in the US—aims to account for some of these possibilities by putting an end to anonymous sperm and egg donation. Under the law, all Coloradans conceived via donors will have the right to find out their donor’s identity and access their medical records upon turning 18.

The legislation places the onus of responsibility on the cryobanks, agencies, and clinics that collect and store donor sperm and eggs, charging them with updating donor records and contact information every three years.

In the age of online DNA tests like 23AndMe, anonymity isn’t something that any donor can count on. But the Colorado law, which also caps at 25 the number of families that have access to a particular donor, is attracting widespread attention because of its implications for the donor gamete industry, which has thus far had much less oversight in the US compared to the UK, Australia, and many European countries.

At the heart of the controversy around industry regulation is the question of what donor-conceived people are owed—not just by the parents who raise them, but by the entire ecosystem of individuals who bring them into existence.

Growing societal acceptance of same-sex parents and single parents by choice has turned donor gametes into a $5 billion global industry. In 1995, 170,701 women in the US used donor sperm, while 440,986 opted for donor sperm between 2015 and 2017.

This means the donor-gamete industry faces increasingly pressing ethical and legal questions, particularly as early generations of donor-conceived people, now well into their 30s, share their own experiences. Some of them say that allowing anonymous donations can lead to harmful psychological and medical consequences for donor-conceived individuals, and warn of the shock that can come with the discovery that one has dozens of half-siblings—or even 150—from the same donor.

Advocates for regulation also point to cases in which parents have discovered that gamete banks failed to check up on donors’ self-reported medical histories, resulting in children born with genetic disorders for which the parents had no idea they might be at risk.

At the same time, attempts to regulate this field may inevitably run up against the reality that it’s hard to exert control over how families—biological or otherwise—take shape.

“This is a really interesting version of society, because there’s all these biological ties, but not necessarily in the context of all being part of the same family—which is the way we’re used to experiencing our biological ties,” says Jaime Shamonki, vice president of clinical strategy and market development for CooperSurgical, the women’s health company that owns California Cryobank. “So I think that tension is there.”

Why regulating sperm and egg donations is so controversial

Erin Jackson, who found out at age 35 that her biological father was a sperm donor, helped shape the Colorado legislation. “I’d assumed both of my parents were genetically related to me, and it was mind-blowing to discover that wasn’t true,” says Jackson, who started a resource group for donor-conceived people in 2016 and later co-founded the nonprofit advocacy group US Donor Conceived Council. “But what was even more shocking to me was learning about the lack of regulation in the industry.”

Right now, the main regulations faced by gamete banks in the US are Food and Drug Administration requirements, which include the stipulation that donors receive physical exams and fill out their medical histories, and that donor samples be tested for infectious diseases like HIV.

The rules may be toughening, though. In addition to the Colorado law, the federal bill HR 8307, introduced this summer, would require gamete banks to collect and verify donors’ medical records. And California’s state legislature passed a bill this summer that would have required gamete banks to provide more education to prospective donors and parents. That bill, however, was vetoed by California governor Gavin Newsom in September, on the grounds that it would have a “limited impact” because it applied only to gamete banks as opposed to all providers in the donor-gamete industry.

“What was even more shocking to me was learning about the lack of regulation in the industry.”

Critics of the Colorado law say the additional regulations are impractical and represent more government intervention in Americans’ reproductive decisions—a major concern as many states enact sweeping new abortion restrictions in the wake of the US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.

“We think reproductive autonomy is a fundamental human right,” says Sean Tipton, a spokesperson for the nonprofit American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). “We think decisions about if and how to build a family need to stay in that family. We don’t think the legislature should make those decisions.”

The ethics of sperm donation

I should mention that I have a personal stake in parsing the issues surrounding sperm and egg donation. I’m currently trying to have a child via donor sperm purchased at California Cryobank.

I don’t know yet how my story will turn out. I also don’t have enough experience with the donor industry to have a strong opinion about the prospect of more regulation—though the idea that introducing more rules could benefit donor-conceived people’s health and well-being certainly has its appeal.

What I have spent a lot of time thinking about is how my hypothetical future child might feel about not knowing their biological father. Anonymity isn’t the issue: California Cryobank stopped accepting anonymous donors in 2017, though it still sells frozen sperm that was donated anonymously before the rule change. I’ve chosen a donor who’s agreed to ID disclosure, which means any offspring should be able to learn the donor’s name and access other identifying information upon turning 18.

It’s possible my child won’t think much about their genetic background at all. But they might want more of a relationship, or more information, than the donor is willing to give.

I worry about the risks involved in trying to have a child this way: The potential for my child to feel hurt or deprived, whether they might need connections or knowledge that I wouldn’t be able to provide. And yet aren’t those risks always present—albeit in various forms—whenever people become parents?

“Outside of donor-conceived children, not everybody gets access to their parents for a myriad of reasons,” says Andrea Braverman, director of psychological services at California Cryobank, who works with donors. “You can’t just put this in a bubble and say, ‘Let’s do what’s ideal.’ Nobody lives in a bubble.”

Of course, it’s one thing to acknowledge that not everyone will have access to their biological parents—and another thing for a prospective parent to actively choose that fate on behalf of their kid. I’m trying to make choices as ethically as I can, but that means putting a lot of trust in an industry that hasn’t always proven itself worthy of trust, with extreme cases involving banks mixing up donor-sperm vials and falsely advertising donors as having received genetic testing when they haven’t. And yet I’m also grateful for the existence of the donor industry, which has given me and scores of other people hoping to start families options that we wouldn’t otherwise have.

The rise of the donor-gamete industry

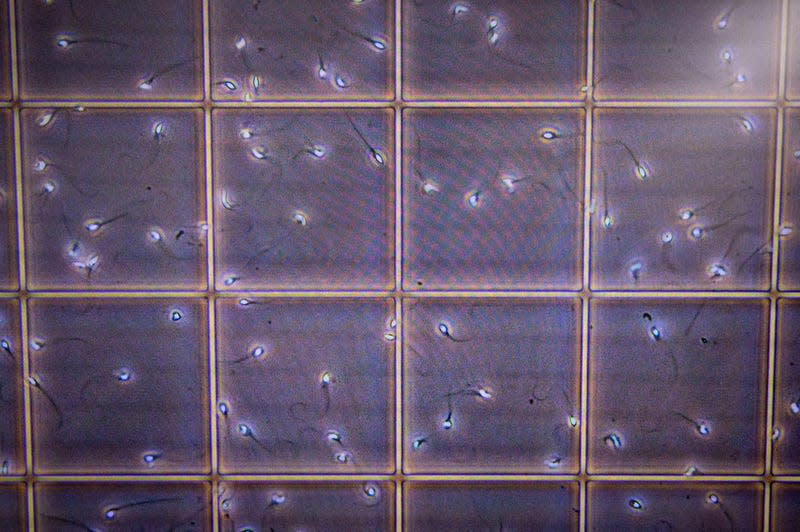

Sperm banks in the US got their start back in the 1950s, when an Iowa fertility clinic successfully impregnated three women using sperm that had been frozen and thawed. But the industry really took off in the 1980s amidst the AIDS crisis, since frozen sperm (unlike fresh sperm) could be re-tested after a quarantine period to ensure that the specimens were negative for HIV.

Egg donation also got its start in the 1980s, and became more popular as in vitro fertilization technology advanced. In the ensuing years, the customer base for donor gametes broadened to include not just heterosexual couples dealing with medical infertility issues but same-sex couples and single parents by choice. An estimated 75-80% of sperm-bank customers today are single women or same-sex couples.

As for the people who decide to become donors, money tends to be at least a partial incentivizing factor. Monthly compensation for sperm donors goes up to $1,500, according to California Cryobank’s website. Egg donation, which involves taking hormonal medications and undergoing a minor surgical procedure, often nets around $10,000. Many banks and agencies advertise donating at university campuses as a way to attract young people looking to pay off student loans.

But sharing your eggs or sperm with others is different from most other gigs in that there are significant long-term consequences.

At California Cryobank, donors receive what the bank calls “implications counseling,” in which the potential questions and complications that might arise in the future are impressed upon them.

“This isn’t donate and done—down the road, there may be a human being or more who have questions or needs that we can’t imagine right now,” says Braverman. “We don’t get to control how donor-conceived persons feel.”

Staffers encourage donors to think about what having biological children out in the world might mean both for themselves and their own future families, and to grapple with the possibility that they might have a significant number of genetic children who come to them looking for answers and, perhaps, relationships. “Are you willing to manage not only that proverbial first knock on the door, but what if it’s the 20th knock on the door?” Braverman asks. “What does that mean for you?”

California’s proposed legislation was intended to prepare prospective donors to think through such possibilities. But even when banks urge donors to consider the future, the truth is that it’s very difficult to predict how you or anyone else will feel decades down the line—a predicament that Braverman acknowledges. She compares the commitment that donors make to marriage: You don’t know exactly what will happen or how your feelings and circumstances might change, but you should still try to think things through before jumping in.

By the numbers

$7.5 billion: Projected value of global sperm bank market by 2030

$5.8 billion: Estimated value of global egg donation market by 2027

24: Number of sperm banks in the US

>75%: Portion of donated-sperm users who have a college degree

$1,045—$1,245: Cost of one vial of donor sperm at California Cryobank

$2,450—$2,750: Cost per donor egg at international gamete bank Cryos International

What donor-conceived people deserve

Parents, donors, doctors, and sperm and egg banks all have a vested interest in the future of donor-industry regulation. But Susan Crockin, a senior scholar at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, says the interests of donor-conceived people have to come first.

“Parents, donors, and sperm banks may have made an agreement, but the kids weren’t part of those agreements,” says Crockin, whose work focuses on the legal issues surrounding assisted reproductive technologies. The right of donor-conceived people to find out information about their identity or medical history “supersedes expectations of privacy or promises of anonymity that donors may have been given in the past.”

For people like Jackson, the woman who found out in her 30s that she’d been conceived via sperm donor, the potential pitfalls of growing up with scant information about your parentage aren’t at all hypothetical. She’s experienced them herself and sees dilemmas playing out every day among members of her Facebook donor-conceived community.

“Parents, donors, and sperm banks may have made an agreement, but the kids weren’t part of those agreements.”

Jackson doesn’t object to the existence of sperm and egg donation. “I don’t think that industry is going anywhere. People who want babies, really want babies,” she says. But she thinks the donor industry has a responsibility to help people learn about their backgrounds.

“It’s just human nature to seek that information,” she says, comparing the experiences of donor-conceived people to those of adoptees. “And I think designing a system that separates people from crucial information about their own identity and families is a human rights violation.”

Jackson cites the example of a woman in her We Are Donor Conceived group who discovered that she was half Ashkenazi Jewish upon taking a DNA test. “She ended up getting the truth out of her parents” about being donor-conceived, Jackson explains. The woman got tested for the BRCA gene mutation, which puts people at a higher risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer and is more prevalent among the Ashkenazi population, and tested positive. As a result, she opted for preventative surgery and gained potentially life-saving knowledge that she would have otherwise never thought to check for.

Jackson also worries that the lack of regulation in the donor industry means that people can potentially have huge numbers of half-siblings. The ASRM recommends that banks and agencies cap egg donors at no more than six egg retrievals, and limit the number of families that can use a particular sperm donor to 25. But banks—now with the exception of those located in Colorado—are not legally required to follow those guidelines.

Even when banks do abide by the ASRM recommendations, it’s possible for people conceived via sperm donor to have around 50 half-siblings, since families using a sperm donor may have more than one child. And donors can also skirt limits by signing on with new banks without disclosing their past donations. There is no US or international registry of donors, which means that banks have no way of checking if a person has previously donated elsewhere

“It’s psychologically damaging to know that you have so many siblings,” Jackson says, noting that she assumes she has at least 100. “It really makes you feel like a thing—like an object, commodified.” Many other countries set a much lower limit on the number of families that can use a particular sperm donor. In the UK, the limit is 10; in Belgium, it’s six.

Many of the people in We Are Donor Conceived have a desire to form relationships with their genetic relatives, Jackson says, whether that means exchanging an email or two or trying to forge close bonds. But the more people you’re related to, the harder it is to make a connection with each one of them.

What can donors be expected to give?

Even if the interests of donor-conceived people trump those of other parties, donors may also be impacted by the introduction of new regulations. For one donor’s perspective, I turned to Rachel Lemmons, a 32-year-old mother of one in Denver, Colorado, who belongs to the support and advocacy group We Are Egg Donors.

While in graduate school for environmental sciences in her 20s, Lemmons decided to donate her eggs. “I had a really close friend of mine go through infertility at a really young age, and she used an egg donor to conceive her daughter. And I just thought it was a really cool thing to see that, you know, just a couple of weeks out of someone else’s life was able to change her life so drastically,” she says.

When Lemmons first donated her eggs in the spring of 2016, she was 25. In the ensuing years, she’s done more rounds, and five children thus far have been born using her eggs.

One of Lemmons’ donations was anonymous, while the rest were open, meaning that she and the parents had one another’s names and could exchange emails throughout the process. When Lemmons considers the possibility that the people conceived with her eggs might get in touch as they grow older, she’s open to it—with caveats.

“I’m fine with them asking me questions about my background or where they come from,” she says. “But I think that if they wanted something more beyond that—like being in touch weekly or daily—I think that might be a little bit too frequent for me.”

The issue, she says, is one of limited emotional availability. “If you’re going to have relationships with all of those children, it really spreads your time thin, especially when you’re trying to focus on your own child, your own family.” The frequency and depth of contact between donors and their offspring, of course, is not something that can be regulated.

But Lemmons thinks that introducing new regulations could benefit donors, too—for example, a system that allows for better tracking of the number of babies born from donated gametes. “There’s donors that have no clue how many of their [genetic] children are out there, and their own children have the same concerns, too.”

Still, she does take issue with some aspects of the Colorado bill—specifically, she says, “the information wasn’t a two-way street.” For example, the law requires banks and agencies to periodically update the donors’ medical information for the benefit of donor-conceived people. But it doesn’t include anything about donor-conceived people sharing health updates with donors. Learning about her biological children’s health conditions “could affect how I get my own medical treatment and how my daughter gets her medical treatment,” she says.

The potential drawbacks of donor-industry regulation

Lemmons is far from alone in having questions about the Colorado law. Eric Surrey is a reproductive endocrinologist at the fertility clinic CCRM in Colorado, which works with egg donors. He doesn’t necessarily object to the goals of the law, but says there’s “very little clarity about how a professional or an organization or clinic can realistically comply.”

On a practical level, critics like Surrey say, it may be impossible for sperm and egg banks to keep accurate, up-to-date records of donors and track the number of babies born. Donors inevitably move between states or even countries, and they may not keep up communication when the banks attempt to contact them every few years.

The same concern applies to parents, of whom an estimated 20-40% actually report live births back to sperm banks—making it difficult to uphold restrictions on the number of families that use a given donor.

“Once a specimen leaves our facility and goes to someone who’s doing home insemination or a physician’s office or a fertility center, we have zero control over that specimen,” says Betsy Cairo, executive director of CryoGam Colorado sperm bank. “You can’t force people to fill out forms. That’s a violation of their privacy.”

Surrey is also concerned about how requiring donors to give access to their medical records—whether the information those records contain involve hereditary conditions or not—could impact donors’ right to privacy. Sonia Suter, a professor at George Washington University Law School, recently told Wired that medical records could, for example, include information about an egg donor’s abortion, which could in turn expose the donor to criminal charges depending on the state where they reside.

The politics of regulating reproduction

Another frequently cited issue when it comes to the prospect of ending anonymity is the impact that such laws could have on the supply of sperm donors—particularly when there’s already a significant shortage in the US. One 2016 study of anonymous sperm donors in the US found that roughly a third said they would not have chosen to donate if they were required to have their names added to a registry so that their genetic children could contact them upon turning 18.

On the other hand, after the UK ended anonymity for donors in 2005, the number of women choosing to become egg donors fell initially but then rebounded, while the number of new sperm donors didn’t dip at all.

It may be that when laws change, the pool of potential donors changes, too. Braverman says that’s what California Cryobank found after ending anonymity. “We did lose a significant number of folks,” she recalls. But the donors who weren’t dissuaded were people with more altruistic motivations to help people start families—an outcome the bank accepted as a positive tradeoff.

The legal experts on the fertility industry I spoke with tended to be amenable to the prospect of introducing new regulations around issues like anonymity and sibling numbers. “Colorado is pretty bold, but it’s going in the direction that this is going anyway,” says Crockin. But they agree there are potential political ramifications anytime the government weighs in on the reproductive sphere.

Judith Daar, a professor of law at Northern Kentucky University who’s authored multiple books on reproductive technologies and the law, says it’s crucial to apply what she calls “the equality lens” to any regulation involving assisted reproduction. That means asking “whether people’s privacy rights and intimate relations rights would be violated in that way if they weren’t producing children through medical assistance.”

In the US, for example, the government doesn’t place limits on how many children a couple is allowed to have—though presumably few would choose to have 25 or more.

The end of secrecy

While the Colorado law may point to the future of donor-industry regulation in the US, the norms around using donor eggs and sperm already seem to be changing faster than the laws that govern them.

Decades ago, it was far more common for parents to keep the fact that they’d used donor sperm a secret from their children. In a 2021 survey of 148 donor-conceived people, the majority of whom were 30 or older, 81% said that they grew up unaware of the truth about their conception.

Now, Crockin explains, donor-conceived people typically grow up with a lot more knowledge about their origins. “Much of the sperm and egg donation field is driven by same-sex couples and single parents by choice,” she says. “Those are families that are, by nature, going to be more open with their children because obviously they couldn’t have been conceived without some form of donation.”

Anecdotally, Crockin says, parents today also prioritize finding donors who are willing to have some kind of contact with their children when they turn 18. The donor industry is evolving accordingly. Fairfax Cryobank—another large sperm banks in the US—also stopped accepting anonymous donors in 2020, while donors at Seattle Sperm Bank sign paperwork agreeing to at least one contact with offspring.

“People’s desire for genetic knowledge does not exist in a vacuum.”

Given that sperm and egg banks are still relatively recent developments, there’s not a lot of long-term research available on the experiences of people who grow up knowing they were donor-conceived. But a longitudinal 2020 study published in the journal Fertility and Sterility offers a hopeful outlook on what the future might look like.

The study looked at the experiences of 76 donor-conceived people in their 20s who had been raised by lesbian parents, interviewing them in six waves beginning in 1992. Both in childhood and adulthood, the researchers found that donor-conceived people’s psychological health was “the same or better” than that of their peers. Most of the people who’d met their donors felt positively about the relationship they had. Among those who didn’t know their donors, the majority were neutral or comfortable with that situation, too.

The study’s sample size was small, and the participants weren’t necessarily representative of all donor-conceived kids. But researchers at The Sperm Bank of California opined in a write-up of the study that the findings suggest most people’s experiences with their donors “are neither catastrophic nor positively world-changing, but instead fall somewhere in the middle.”

Greater industry regulation, whether on a state or federal level, could nudge donor-conceived people’s experiences in an even better direction. It could also unleash new dilemmas. Or, depending on how tricky the laws are to implement and enforce, regulation might change very little at all.

It’s also possible that, as use of donor sperm and eggs becomes more common, people’s feelings about the importance of genetic relationships will evolve, too. “People’s desire for genetic knowledge does not exist in a vacuum,” philosophy professor Daniel Groll wrote in an article for the Center of Bioethics at the University of Minnesota last year. Rather, people tend to possess “a culturally-mediated desire, one that reflects problematic attitudes about what families are, and should be, like.”

That doesn’t mean that banks, or parents, should deny donor-conceived people knowledge about the people who share their DNA. For now, we live in a culture that emphasizes the importance of genetics, and lots of people turn to their family trees in the quest to understand themselves better.

But in an era in which the ideas of chosen families and other family structures that buck the nuclear tradition are increasingly taking hold, perhaps we can look forward to a future where people have the option to learn about their donors and get to know their siblings, if they so choose—but in which the nature of their conception also feels less outside the norm, and more like one option among the myriad ways that people find to bond themselves to one another.

More from Quartz

Sign up for Quartz's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.