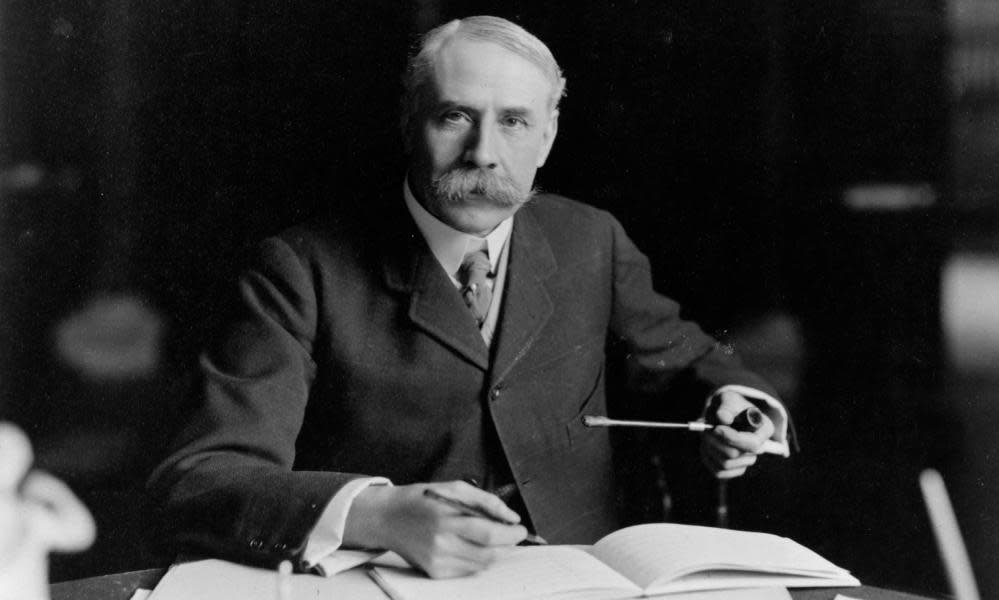

Elgar: where to start with his music

If Britain has a national composer, it is Edward Elgar (1857-1934). His music is often seen as epitomising the smug Victorian world into which he was born, but though he wrote his quota of “patriotic” pieces, he was much more than a flag-waving imperialist; his influences and musical outlook were profoundly European rather than home-grown. Elgar was the most significant composer Britain has produced since Henry Purcell, and his finest music – the symphonies and concertos – easily stands comparison with that of his late-romantic contemporaries Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler.

The music you might recognise

Two of Elgar’s melodies are ingrained in the fabric of British culture. Land of Hope and Glory, which sets jingoistic words by AC Benson to the melody from the first of the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, has become an ersatz national anthem and, as events this summer proved, an apparently obligatory part of the Last Night of the Proms, while the elegiac Nimrod, the ninth of the Enigma Variations, which Elgar intended as a musical portrait of his publisher August Jaeger, has become a go-to memorial piece.

His music has cropped up in unexpected places, too. Kanye West, Muse and Rob Dougan (Clubbed to Death) are among the contemporary musicians who have quoted it. The 1984 movie Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, features both the First Symphony and the popular salon miniature Salut d’Amour; Disney’s remake Fantasia 2000 uses the Pomp and Circumstance March No 2 to introduce Donald Duck, and, more recently Nimrod helped advertise Carling lager. Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro for strings provides the backdrop to the memorable opening sequence in Ken Russell’s superb 1962 TV drama documentary, Elgar: Portrait of a Composer, as the young composer rides a horse across the Malvern hills.

His life

He was born in Broadheath, a few miles from Worcester, where his father ran a music shop and tuned pianos. He was brought up a Roman Catholic – his mother had converted shortly before Edward was born. Though he was taught the piano and violin as a child, he taught himself to play other instruments, and he was entirely self-educated as a composer – his parents could not afford for him to study in Leipzig as he had hoped.

Through the 1880s, he worked in the Worcester area as a freelance musician, conducting and composing for local choirs and orchestras, playing the violin in Midlands orchestras and the bassoon in wind bands. He recycled some of the music he composed at that time in the two Wand of Youth suites (1907), but his earliest original piece that’s regularly heard now is Salut d’Amour, written in 1888 as an engagement present for his future wife, Caroline Alice Roberts. Alice was determined to establish Elgar as a great composer, and suggested the couple move to London, where she hoped to interest publishers and conductors in his music. Their stay there lasted a couple of unsuccessful years, before they returned to Malvern, and it was in Worcester, at the 1890 Three Choirs festival, that the concert overture Froissart, now recognised as his first major work, was premiered.

A series of choral works composed in the 1890s for festivals in Birmingham and Worcester – The Black Knight, King Olaf, The Light of Life – and the cantata Caractacus, written for the 1898 Leeds festival, at last began to attract wider attention, but it was the 1899 premiere in London of the Variations on an Original Theme, now usually known as the Enigma Variations, that established Elgar as the leading British composer of his generation.

The name “Enigma” comes from Elgar’s disclosure that another unstated theme, a well-known melody, runs through the work alongside the one on which the 14 variations, portraits of the composer’s friends, is overtly based. Despite many claims, no one has yet convincingly demonstrated what that theme might be. Musically, however, it’s a work that brings together the two crucial stylistic influences on Elgar’s music; using variation form, which was favoured by Brahms and Dvořák, to underpin an extra-musical narrative – the portraits of friends – which suggested connections with the symphonic poems of Liszt and Strauss.

…. and times

Immediately after the variations Elgar began what is arguably his greatest work, The Dream of Gerontius, a setting of John Henry Newman’s poem, portraying the journey of a man’s soul from his death bed to his judgment before God. It’s the closest Elgar ever came to an opera (though a few years before his death he did contemplate writing one, The Spanish Lady); the influence of Wagner’s Parsifal, which he had heard twice on a visit to Bayreuth in 1892, is clear from the prelude onwards.

Elgar, a self-taught composer and a Roman Catholic from a relatively humble background, always regarded himself as an outsider in the musical world, but the impact of the Enigma Variations ensured that he was rapidly assimilated into its staunchly Anglican mainstream. Even the overt catholicism of Gerontius – condemned by the influential composer Charles Villiers Stanford as “reeking of incense” and banned from performance in Gloucester Cathedral – was not enough to keep him from being welcomed into the British establishment. For the coronation of Edward VII in 1902, he was commissioned to write a Coronation Ode, into which he incorporated Land of Hope and Glory, and in 1904 he was knighted and a festival of his music was held at Covent Garden in London.

The 1900s were a period of intense productivity. Two large-scale biblical oratorios, The Apostles and The Kingdom, had followed Gerontius, though the third part of what was intended as a trilogy never got beyond a few sketches (because, it’s been suggested, Elgar had begun to lose his religious faith). The most Straussian of all his works, the concert overture In the South, appeared in 1904, and the Introduction and Allegro for strings the following year.

His First Symphony had its roots in an earlier idea to compose a work commemorating the life of the Victorian hero General Gordon, but the score that appeared in 1908 had no overt programme, just as the Second Symphony (1911) begun as a memorial to Edward VII, evolved into a satisfying abstract musical construction. Where the First Symphony and the Violin Concerto were hugely successful from the start, the Second Symphony, with its quiet, equivocal ending, was less well received.

The last two major works from the years before the outbreak of war, the choral ode The Music Makers, a score laced with self-quotations (rather like Strauss’s tone poem Ein Heldenleben), and the symphonic study Falstaff, had lukewarm receptions, too. When the hostilities began, Elgar produced a series of “patriotic” pieces, the most substantial being the choral tribute to the fallen, The Spirit of England. Three chamber works, a violin sonata, piano quintet and string quartet, composed in 1918 and 1919, provided a welcome escape from the horrors of the war, but Elgar’s despair at the carnage emerged most poignantly in what proved to be his final large-scale work, the Cello Concerto, first performed in 1919 in a disastrous premiere.

Alice died the following year. Elgar moved back to Worcestershire, but composed little. He did travel, however, voyaging up the Amazon to Manaus in 1923. There is no detailed account of his trip, but it formed the basis of James Hamilton-Paterson’s prizewinning novel Gerontius. Elgar’s brand of late Romanticism had become unfashionable in the jazz age, although younger conductors such as Adrian Boult and John Barbirolli continued to champion his works, and the BBC commissioned a third symphony that Elgar was working on in the final year of his life. In the 1990s, composer Anthony Payne produced an “elaboration” of the sketches, first performed in 1998.

Why he still matters

Born a year after the death of Schumann, he died the year before Alban Berg, yet Elgar’s music remained firmly rooted in the late-Romantic tradition. He not only ignored the currents of modernism that swirled around European music from the 1890s onwards, he also disdained the tropes of English folksiness that the subsequent generation of British composers led by Vaughan Williams would embrace. If his works are regarded as “English” at all in a stylistic sense, it’s because they actually defined English music. Elgar created the model himself, single-handedly.

Great performers

The Elgar legacy on record begins with the composer himself, who started conducting acoustic discs of his works as early as 1914, and made electrical recordings of his major works from 1926 onwards; one of the last of them was the historic 1932 performance of the Violin Concerto, with a 16-year-old Yehudi Menuhin the soloist. Almost all leading British conductors of the last century have included Elgar in their repertoires. Boult recorded all the major works several times; Barbirolli’s recordings include the celebrated performance of the Cello Concerto with Jacqueline Du Pré, and what is arguably the finest of all versions of The Dream of Gerontius. More recently, Colin Davis, Richard Hickox and Mark Elder have all made hugely impressive Elgar recordings, and different perspectives on the music have come from farther afield with the performances by Georg Solti, Bernard Haitink and Daniel Barenboim.