How Emmerdale has broken new ground with Marlon's storyline

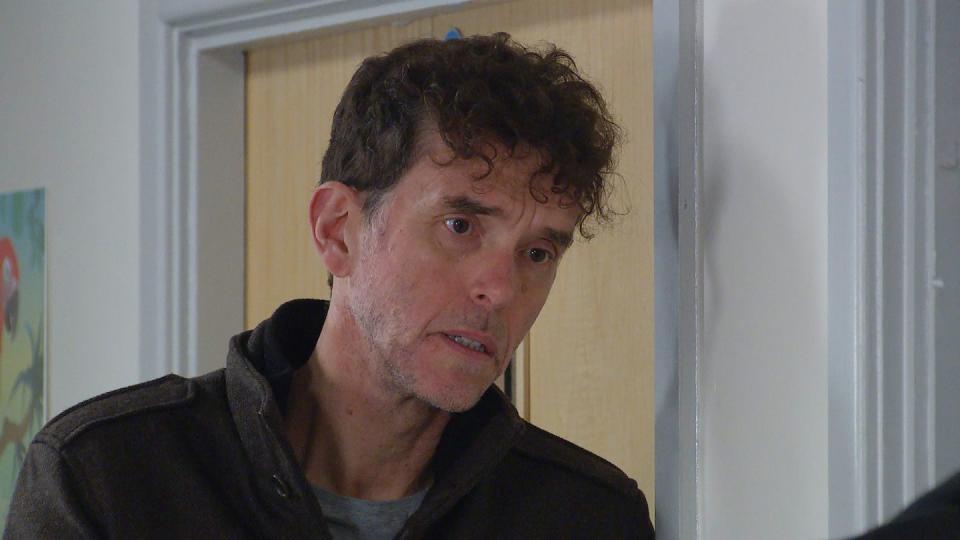

When Marlon Dingle looked in the mirror and saw the signs of a stroke, Emmerdale embraced knotty, thoughtful, relatable disability representation: piecing together the inner lives of disabled people through the eyes of a physically expressive character we've forged a relationship with over decades.

The soap and the (non-disabled) actor are embracing a responsibility to preserve, retell and revise the disabled experience on screen.

It's a portrayal that finds truth in its emotional beats – when Marlon hunches over as he puts too much pressure on his crutch, the strain on his face when his body wearies, the gritted teeth and white knuckles.

Emmerdale has also deliberately constructed a natural piece of disability representation by taking words and direction from people with lived experience, such as the actor James Moore, who plays Ryan Stocks in the show.

James said: "I actually gave a lot of advice to writers about this storyline. A lot of it comes from real experiences I've had from people treating me different because of my disability."

I mention the scene which resonated with me most, as being so near the knuckle: Marlon's first return to The Woolpack after his stroke, the place full of dehumanising comments about his disability, and clumsy condescending interactions such as: "You don't want him stuck in that longer than he needs to be."

Disabled people often have to bear the discomfort of other people's misconceptions and assumptions: blank stares and ignorant opinions. Moore agrees: "I like that scene, and I think they've done a really good job relating our experiences."

Earlier stories were built from one truth – that stereotypes sell. Slovenly thinking is endlessly churned out.

As Dr Kirsty Liddiard from the University of Sheffield states: "Marlon Dingle's current storyline in Emmerdale is really important towards raising awareness of the longer-term effects of having a stroke."

Marlon's post-stroke experiences have included surgery, aphasia, difficulty with his language and speech, a sudden shift in agility and mobility, new clinical vulnerability, ensuing re-hospitalisation, and the need to relearn basic processes such as swallowing.

The soap has also integrated scenes within the recovery process to demonstrate that real recovery is often knotty and frustrating, not linear, and that setbacks can be disheartening.

For example, when Marlon returned home from the hospital, his daughter April Windsor gave him a drink and he choked as he gasped for breath and his body shook. Still, gradually, he was able to relearn how to swallow, and he was able to taste small amounts of cake for his wedding.

As Dr Liddiard suggests, this depiction can transform thoughts of stroke and acquired brain injuries as simply one-time events: "Sudden illness can enable us to re-evaluate our outlook, future, and identity. Realistic depictions like this show that people can and do live good lives with disability and illness."

Medicine cannot and doesn't need to 'cure all' or offer miracles beyond reasonable care and support. Marlon's life is ordinary, entwined around new realities – altered by a moment in time, but anything else would be careless misdirection and half-truth.

Old ideas around miracle cures in soap and other media have created a model of the stylised "good disabled person". There's a clarity and neatness that the non-disabled expect, and an obvious resolution.

For example, Hollyoaks Carmel McQueen's facial scarring was sustained when a tanning machine blew up in her face. Afterwards, we were reassured that Carmel's scarring was permanent and the consequences would shape her future and perspective. But it was ultimately cured and forgotten.

When Sinead Tinker's spinal injuries on Coronation Street left her unable to walk and required intensive physio to help her recover the use of her limbs, she was cured months later, which does little to replicate the real-world experience.

Emmerdale needed to entwine Marlon's experience with Paddy Dingle's disappearance: not the spectre of a disabled body breaking down, but as an individual with a disability simply going through it – an acknowledgement that many live with and around their disability throughout their lives.

When Marlon communicates his irritation that the stress and anxiety of the situation have exacerbated his condition – "I thought I was well past all this" – he's relatable.

My speech often fluctuates, and my voice slurs when I am tired or anxious. Marlon's experience feels familiar. An arm unable to move the way you want it to, a hand unable to write without a furrowed brow and an effort which contorts your face – grappling with years of physiotherapy, worrying about COVID or another vulnerability around the kitchen table or falling over hastily discarded trainers.

Even decades after my stroke, the physical signs still shape my life. For example, I have had my hips broken and my knees rebuilt. A lack of balance means I need crutches and a wheelchair – the physical grind of putting one foot in front of the other is exhausting.

There is honesty in the lines on Marlon's face, the bare emotion. Most films and TV shows have the disabled die, get better, or leave to live off-screen. The truth of it is most of us learn to deal with it as part of our ordinary lives. Nothing I've seen shows that fully.

Marlon's stroke story is crucial for disability representation because it legitimises real experiences – it offers no neatness or clarity, and such a knotty, thoughtful portrayal is that rare thing in disability representation: relatable.

Emmerdale airs on weeknights at 7.30pm on ITV1, and streams on ITVX.

Read more Emmerdale spoilers on our dedicated homepage

You Might Also Like