The EPA Grossly Underestimated How Many Carcinogens are Polluting This Louisiana Region's Air, Study Says

A chemical plant-smattered stretch of Louisiana between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is already known as "Cancer Alley" due to disproportionately high levels of illnesses related to chemicals released by the area's many manufacturing facilities. Now, according to a new study from researchers at Johns Hopkins University, the stretch of land — which, again, is already called Cancer Alley — is even worse off than scientists already thought.

The study, published this week in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, examined the rates of a toxic gas called ethylene oxide in the air covering the Louisiana region. Ethylene oxide is a known and potent carcinogen linked to lymphomas, breast cancer, and other health and life-threatening illnesses, and was banned in the European Union back in the early 1990s. But ethylene oxide is used to manufacture other chemicals, and though the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recognizes its toxicity, chemical plants in Louisiana's Cancer Alley stretch continue to use the poisonous gas in their production processes — and as a result, leak ethylene oxide into the air.

And yet, though it's long been known that the plants leak the poisonous gas, this new Johns Hopkins research finds that the EPA has been grossly underestimating exactly how much ethylene oxide is actually in Cancer Alley's air. According to these new findings, the area's average ethylene oxide level is double what previous EPA models suggested — and well beyond levels considered safe for area inhabitants.

"We expected to see ethylene oxide in this area," said study senior author Peter DeCarlo, an associate professor at the university's Department of Environmental Health and Engineering, in a statement. "But we didn't expect the levels that we saw, and they certainly were much, much higher than EPA's estimated levels."

As explained in the study, any level of airborne ethylene oxide above 11 parts per trillion (PPT) is considered dangerous for long-term exposure (which, we should note, isn't really that much, and speaks to how toxic the gas is.) Horrifyingly, the researchers found ethylene oxide levels above 11 PPT in three-quarters of the overall area they studied, with average levels for affected areas hovering around 31 PPT.

"We saw concentrations hitting 40 parts per billion," said DeCarlo, "which is more a thousand times higher than the accepted risk for lifetime exposure."

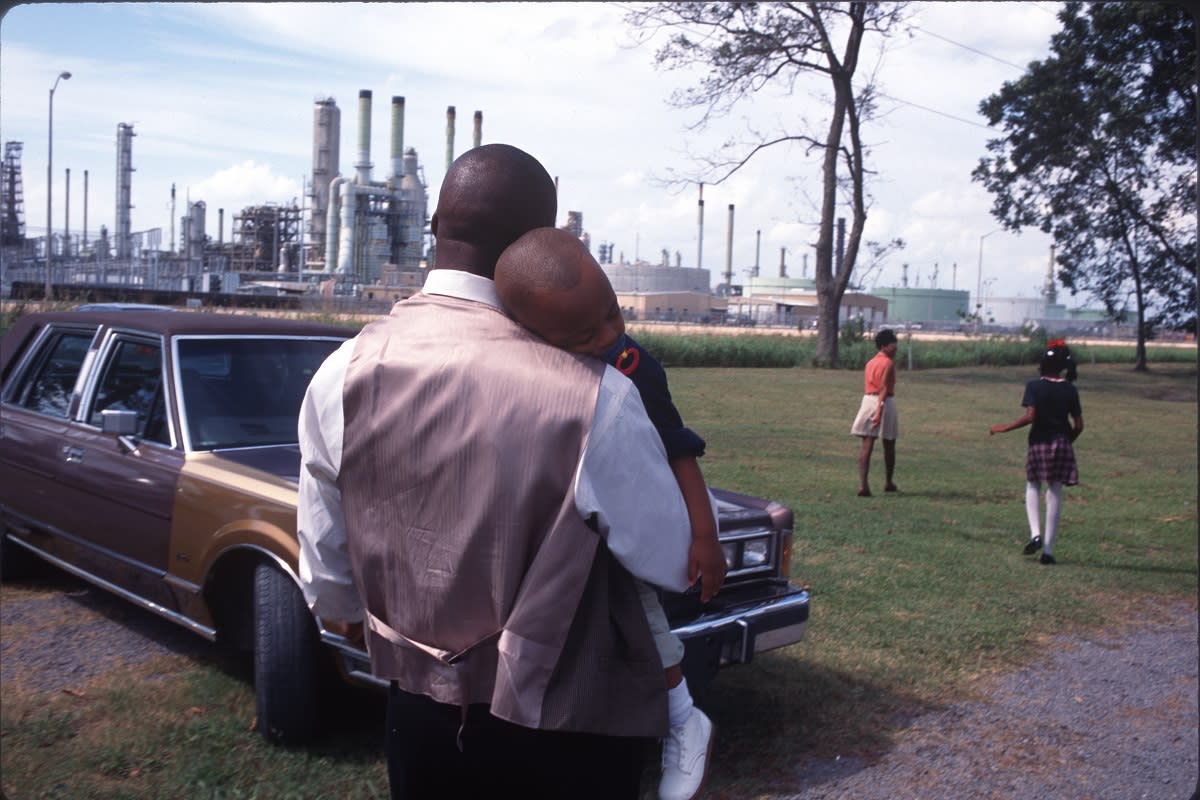

The findings are staggering. And as the researchers note, those who live and work in the area have never — until now — had access to this kind of detailed, accurate data about ethylene oxide figures. And it's important to note that Cancer Alley's Black residents are disproportionately likely to develop petrochemical industry-related illness, and that the EPA has openly accused Louisiana lawmakers of engaging in environmental racism.

"There is just no available data, no actual measurements of ethylene oxide in air, to inform [plant] workers and people who live nearby what their actual risk is based on their exposure to this chemical," DeCarlo added.

As Grist reports, the EPA — which very much needs to update its modeling data — moved this year to install heavier regulations on ethylene oxide use and emissions. And though that's certainly a necessary step, experts have continued to warn that the agency and other regulating bodies have been very slow to take it.

"The fossil fuel and petrochemical industry has created a 'sacrifice zone' in Louisiana," Antonia Juhasz, a senior researcher on fossil fuels at Human Rights Watch, said earlier this year after the global nonprofit released a devastating report about the health consequences of Cancer Alley's rampant chemical and fossil fuel pollution. "The failure of state and federal authorities to properly regulate the industry has dire consequences for residents of Cancer Alley."

Indeed, mitigating future exposure through strict regulations is essential. But so, too, is supporting the people and communities currently living ethylene oxide's harms.

"These monitors are good," Rise St. James founder Sharon Lavigne, whose community action group opposes petrochemical expansion, told Grist of the Johns Hopkins report. "But in the meantime, people are dying."

More on pollution: Scientists Discover the Villains Destroying the Planet