Fentanyl users get free smoking gear in some cities. Now there’s pushback.

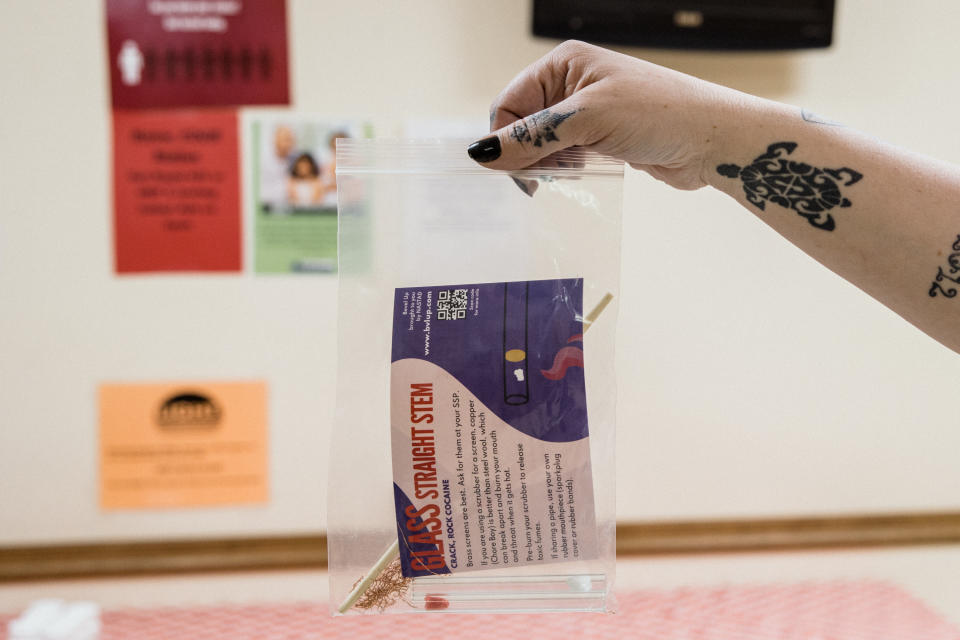

<p>MORGANTOWN, W.Va. - For years at this<b> </b>downtown public health clinic, staffers have given drug users small glass pipes along with sterile needles and other supplies. The strategy: Users might choose to smoke street drugs - limiting infected wounds and the spread of diseases that come with injecting.</p> <p>Some public health advocates and drug users believe smoking fentanyl - the street opioid fueling thousands of deaths - may also lessen<b> </b>chances of a fatal overdose compared with injecting the drug. Scott, a user picking up supplies on a recent weeknight, now smokes fentanyl more than he uses needles because injections caused his hands to swell and damaged his veins. He said he overdosed twice when injecting fentanyl but never while smoking.</p> <p>“I understand why people think it’s enabling users,” said Scott, 38, a former coal miner who spoke on the condition of being<b> </b>identified by first name only to openly discuss his addiction. “It’s actually helping more than people think.”</p> <p>But starting June 2, it will be illegal for state-authorized syringe exchange groups to supply Scott and other users with smoking paraphernalia.<b> </b>Under a law passed by West Virginia lawmakers, the Milan Puskar Health Right clinic will be banned from giving away pipes, tin foil and other supplies used to consume illicit drugs, even as researchers say more drug users nationwide are turning to smoking. The law is part of broader resistance in communities where critics assert that distributing<b> </b>“safer smoking” supplies encourages substance abuse and could make fentanyl more appealing to new users.</p> <p>The pushback underscores long-standing tensions over strategies aimed at reducing the harmful effects of illicit drugs as the nation grapples with an overdose death toll that has topped 100,000 for three straight years.</p> <p>In Idaho, police raided a Boise harm reduction organization in February on suspicion that it distributed drug paraphernalia. In Oregon, the county health department in Portland scrapped a pilot program to hand out smoking supplies last summer amid criticism. In New York City, vending machines stocked with pipes and<b> </b>the overdose reversal medication naloxone prompted conservative media headlines about free “crack pipes.”</p> <p>South of Baltimore, in Anne Arundel County, the health department halted giveaways of smoking supplies in 2021 after Black leaders protested, saying pipes might enable drug use in communities devastated by crack cocaine decades ago.</p> <p>“The crack pipe represents the worst of that era,” said Carl Snowden, a civil rights activist and member of the Caucus of African American Leaders of Anne Arundel County.</p> <p>- - -</p> <p>‘Hard to leave the needle’</p> <p>Four decades ago, when heroin was the opioid of choice on America’s streets, smoking the drug wasn’t prevalent. For users, the high wasn’t sufficiently robust, said Daniel Ciccarone, a professor of family medicine at the University of California at San Francisco who studies drug use trends.</p> <p>That changed with illicit fentanyl, which has largely replaced heroin in the United States and is up to 50 times more potent. Particularly on the West Coast, users who smoked fentanyl found its vapors hit the brain with speed and potency. They often use tin foil to heat fentanyl, then inhale through straws, foil tubes and skinny glass tubes known as stems.</p> <p>“It’s one person teaching another, and it’s spreading like wildfire,” said Ciccarone, who recently published a study on San Francisco’s fentanyl smoking culture.</p> <p>Research suggests fentanyl smoking is catching on beyond the West Coast, although it remains unclear whether smoking poses less of an overdose risk than injecting.</p> <p>Fentanyl is a powerful sedative and generally wears off quickly. Constant injections can damage veins and create puss-filled skin abscesses. Smoking allows users to titrate doses, said Alex H. Kral, an epidemiologist at the nonprofit research institute RTI International. He suspects that “means you are less at risk of an overdose because you’re not taking as strong a dose.”</p> <p>In a study published in December, Kral and fellow RTI researchers in San Francisco tracked nearly 1,000 drug users and found those who injected were 40 percent more likely to have experienced a nonfatal overdose in the previous three months than<b> </b>those who only smoked.</p> <p>Still, no conclusive evidence exists that smoking fentanyl is less likely to result in overdoses, said Andrew Kolodny, an addiction doctor and opioids researcher at Brandeis University.</p> <p>“If it were the case, as smoking has increased, perhaps we would have seen a significant decrease in overdose deaths - and we haven’t,” said Kolodny, who says the debate detracts from emphasizing<b> </b>addiction treatment.</p> <p>In February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a study that suggested smoking fentanyl was increasingly linked to overdose deaths in 27 states and D.C. The study drew on mortality data from<b> </b>medical examiners and coroners and witness reports. Comparing six-month periods in 2020 and 2022, researchers found overdose deaths with evidence of smoking increased nearly 74 percent, while cases<b> </b>linked to<b> </b>injections plummeted.</p> <p>Some researchers say the increase in deaths reflected in the CDC study might be misleading. They caution against attributing overdose deaths to the discovery of smoking equipment. Smoking supplies found at the scene of overdoses might have been used for other drugs, belonged to other people or been used on previous days, said Jon E. Zibbell, an RTI senior public health analyst studying drug-smoking trends in North Carolina and West Virginia. The shift to smoking isn’t widespread enough to significantly lower overdoses, he believes.</p> <p>“People are smoking, but they’re also injecting,” Zibbell said. “It’s hard to leave the needle.<i>”</i></p> <p>The picture is complicated<b> </b>by users who increasingly use the stimulant meth with fentanyl and often switch back and forth between smoking and injecting<b> </b>both drugs.</p> <p>In Washington state, an April survey of participants in programs that exchange used needles for sterile ones showed 89 percent of users had smoked drugs such as meth or fentanyl within the past week, with 36 percent smoking and injecting and 10 percent injecting. The survey reported “high interest” in getting smoking supplies from harm-reduction programs that don’t already distribute<b> </b>them.</p> <p>- - -</p> <p>Reducing harm</p> <p>Some communities and public health agencies have embraced harm reduction, which focuses on lessening the deleterious effects of drug use. Using clean needles reduces HIV and hepatitis C rates,<b> </b>studies show. Workers also hand out naloxone and<b> </b>condoms and connect people with wound care, disease testing and other medical services.</p> <p>The Biden administration has embraced the approach, although it took a hit in 2022 when conservative media claimed $30 million in federal funds would be used to hand out “crack pipes.” Even as the White House denied the claim, Republican lawmakers proposed banning federal funding for pipes.</p> <p>Safer smoking supplies often include rubber, plastic or silicon mouthpieces to prevent cuts and burns, brass screens to filter contaminants, and disinfectant wipes. That’s<b> </b>safer than items improvised from aluminum cans, lightbulbs or plastic tubes that can break easily or release dangerous fumes, advocates say. Giveaways may also prevent users of other drugs - who may not have a tolerance for opioids - from sharing pipes that contain fentanyl residue.</p> <p>Because many states ban paraphernalia, harm reduction groups that provide<b> </b>smoking supplies tread lightly.</p> <p>Four years ago in Boston, Jim Duffy and Nathaniel Micklos created the group Smoke Works after encountering drug smokers who were not engaging with services offered by harm reduction groups. Today, Smoke Works<b> </b>distributes free or low-cost supplies for smoking or snorting to more than 300 groups nationally. Many don’t want their participation made public because of potential scrutiny, Duffy said.</p> <p>“There’s absolutely no end in sight for hostile enforcement,” he said.</p> <p>Those concerns were underscored in February in Idaho, where police raided offices of the state-funded Idaho Harm Reduction Project five months after employees in a panel discussion suggested program workers had been skirting the law in handing out pipes and supplies for snorting drugs. Boise police said it involved distribution of drug paraphernalia, including items related to the use of meth, opioids and crack cocaine. Syringes were not seized, and no arrests have been made, police said.</p> <p>The program has shut down. And that wasn’t the only development that led to the curtailing of harm reduction programs. Idaho’s Republican-dominated legislature has since repealed a law that authorized syringe-exchange programs, which have come under increasing restriction in some states.</p> <p>States with more liberal politics have also resisted free smoking supplies.</p> <p>In Oregon, the Multnomah County Health Department launched a pilot safe-smoking program because fewer users were getting services at its needle-exchange program in Portland. The department knew it might generate controversy, spokeswoman Sarah Dean said, but proceeded because of surging overdoses. Within a week, the program was halted amid public outcry.</p> <p>This year, Oregon<b> </b>lawmakers rolled back decriminalization of minor drug possession amid concerns about crime and rampant open-air drug use. “The issue around smoking is that while it’s likely to have a public health benefit, it’s very visible,” said Ciccarone, of UCSF. “People don’t like the fact that drug use, which was once hidden, is now very public.”</p> <p>In West Virginia, the Health Right clinic began handing out pipes, stems and foil in 2020 to minimize the spread of the coronavirus through shared equipment. Donations and private grants paid for the supplies.</p> <p>“I’m the director of a medical clinic. I would be the last person to say, go smoke drugs, smoke cigarettes or smoke anything,” Health Right Executive Director Laura Jones said. “But when you’re talking about a harm reduction, it’s a different philosophy.”</p> <p>But the clinic’s harm reduction program came under scrutiny in 2022 when state delegate candidate Geno Chiarelli posted a Facebook video showing a “free meth pipe” and other equipment he said he obtained at the clinic. “These are the kinds of things that are unacceptable in a civilized society,” he said in the video.</p> <p>Chiarelli (R) won election and sponsored the bill this year that prohibited needle exchange groups from giving away smoking equipment. Chiarelli declined to comment.</p> <p>On a recent weeknight, most clients - their arms and veins dotted with reddish puncture marks - exchanged needles at the health clinic. Their stories rang tragically familiar: Pain pill use led to heroin and fentanyl, jails and rehabs. Outreach workers preparing plastic bags filled with supplies and food included pipes from their dwindling cache.</p> <p>“She gave me a pipe and said it would probably be best to try and get off needles,” said A.J., a 28-year-old roofer who uses fentanyl and spoke on the condition<b> </b>that his full name not be used because of his addiction. “I’ll give it a try.”</p>