Gao Yaojie: Dissident doctor who exposed Aids epidemic in rural China dies at 95

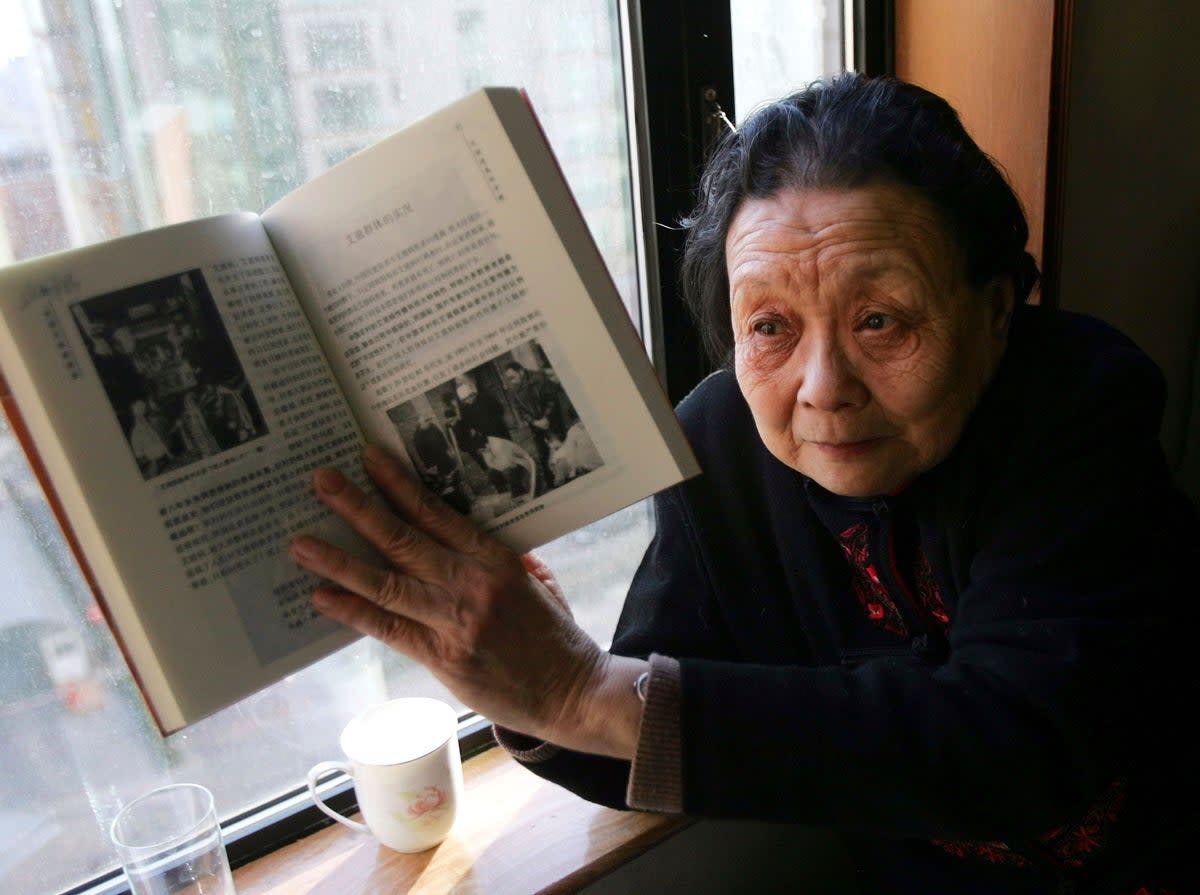

Gao Yaojie, a renowned doctor who exposed the Aids pandemic in rural China, defying government pressure in the 1990s, has died, aged 95.

The Aids activist died of natural causes in New York where she had been living in exile since 2009, Columbia University professor Andrew J Nathan confirmed.

Dr Gao became China’s most well-known Aids activist after speaking out against the blood-selling schemes that infected thousands with HIV in the late 1990s, mainly in her home province of Henan in central China.

Born on 19 December 1927, Dr Gao grew up in the eastern Shandong province during a tumultuous time in China’s history, which included a Japanese invasion and a civil war that brought the Communist Party to power under Mao Zedong.

Her family moved to Henan, where she studied at a local university and later, in 1966, she was subjected to beatings from Mao’s newly mobilised Red Guards – a mass, student-led, paramilitary social movement – due to her family’s “landlord” status.

Dr Gao’s contributions were eventually acknowledged by the Chinese government, which was forced to battle the Aids pandemic well into the 2000s. At least one million people were infected by HIV in China starting in the late 1980s.

But Dr Gao claimed the actual figure to be 10 million.

She discovered that poor farmers were lured into donating blood at ramshackle blood transfusion centres in the Eighties and Nineties.

A roving gynaecologist who used to spend days on the road treating patients in remote villages, Dr Gao met her first HIV patient in 1996 – a woman who had been infected from a transfusion during an operation.

Local blood bank operators would often use dirty needles and, after extracting valuable plasma from farmers, would pool the leftover blood for future transfusions.

“Grandma Gao” investigated the crisis by visiting homes in the villages of Henan. She would sometimes encounter devastating situations where parents were dying from Aids and children were being left behind.

She gave away food, clothes and medicines to ailing villagers – mostly at her own expense.

She spoke out about the Aids epidemic, capturing the attention of the local media and angering the local governments which often backed the blood banks.

Dr Gao said she withstood government pressure and persisted in her work because “everyone has the responsibility to help their own people ... As a doctor, that’s my job. So it’s worth it,” she said in an interview.

She said she expected Chinese officials to “face the reality and deal with the real issues – not cover it up”.

Dr Gao received recognition from international organisations and officials for her relentless work in China, even in retirement.

In 2001, the Chinese government refused to issue her a passport to go to the US to accept an award from a United Nations group.

Henan officials in 2007 kept her under house arrest for about 20 days to prevent her from travelling to Beijing to get a US visa to receive another award.

They were eventually overruled by the central government, which allowed her to leave China. Once in Washington DC, Dr Gao thanked the then president Hu Jintao for allowing her to travel.

“After Dr Gao failed to bring the problem of Aids spread by blood purchase stations to the attention of the Henan provincial government, she brought the story to a reporter for The New York Times,” Professor Andrew Nathan, who helped her settle in New York, told the BBC.

“The story of the Henan blood-sales Aids epidemic [was] on the front page of the newspaper, and it became an international scandal, which then influenced the Chinese government to do something about it.”

Dr Gao was hailed by former secretary of state Hillary Clinton as “one of the bravest people I know”.

She is survived by two daughters and a son.