Gold mining leaves deforested Amazon land barren for years, find scientists

Travel through the rainforest in Guyana, in northern South America, and you’ll often hear the indigenous adage: “a forest has no end and no beginning” to explain their natural cycle of disturbance and recovery. For the people who live in these forests, their experiences are based on decades of slash and burn cultivation, from which forests are generally able to recover well. But does the adage hold true for forests abandoned after more intense land uses?

Gold mining has rapidly increased across the wider Amazon region in recent years, especially along the Guiana Shield, where it is responsible for as much as 90% of total deforestation. The Shield encompasses Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, Venezuela and small parts of Colombia and northern Brazil, and its forests hold roughly 20 billion tonnes of above-ground carbon.

Much of the forest loss within the region is caused by artisanal and small-scale miners who respond quickly to increases in international gold prices. Often, they leave in their wake extensive soil erosion and rivers and streams contaminated with mercury. In the mines, mercury is used to separate the gold that is mixed in soil and sediments, forming a fusion called an amalgam. The mercury is then burned over an open flame to retrieve the gold.

Scientists have previously looked at how forests regrow after being cut down and converted into fields and pasture, and then abandoned. They found these recovering, “secondary forests” were able to maintain biodiversity and accumulate carbon, among a range of other “ecosystem services”. Yet none of these studies had compared forest recovery after farming with what happens after gold mining. So we set out to find out more.

Investigating regrowth in abandoned mines

In 2016 we travelled to two gold mining areas deep in the rainforests of central Guyana – Mahdia and Puruni – and established tree measurement plots in abandoned sites. We covered the three different zones typically found on each site: the mining pit itself; the “overburden”, or pile where topsoil had been deposited; and the tailing pond, which contained deposits of material left over after the gold had been separated from the ore.

We also established control plots in old growth forests to compare our results from abandoned sites, as well as took soil samples from abandoned sites, control plots and active mining sites for comparison. 18 months later, we went back and remeasured all these plots.

Among the lowest recovery rates ever recorded

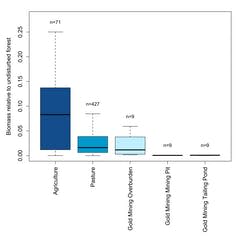

Our research, now published in the Journal of Applied Ecology found that gold mining significantly limits the regrowth of Amazonian forests, and greatly reduces their ability to accumulate carbon. Recovery rates on abandoned mining pits and tailing ponds were among the lowest ever recorded for tropical forests, compared to recovery from agriculture and pasture. At some sites, there was no woody tree regeneration even three to four years after mining stopped, leaving either bare earth or grasses.

Our study estimates that across the Amazon, gold mining causes about 2 million tons of forest carbon to be lost each year. The lack of regrowth we observed shows that this lost carbon may not be recoverable, within what would be considered normal regeneration time frames, simply by leaving these abandoned mines to nature.

We found that the recovery process is primarily dependent on the availability of nitrogen, a critical component that trees need in order to grow, and less on the level of mercury contamination. Nitrogen is found in the topsoil which is stripped away during the mining process, and was significantly lacking in mining pits and tailing ponds, making it difficult for forests to re-establish themselves. On the overburden, however, where there was more nitrogen left in the soil, recovery rates were similar to abandoned pasture or agriculture.

We also observed that active mining sites had on average 250 times more mercury concentrations than abandoned sites, indicating that once a mine is closed down most of the mercury leaches into neighbouring forests and rivers. Mercury pollution is especially harmful to fish, which are an integral part of local and indigenous communities’ diet in this part of the world.

The slower recovery due to mining is particularly concerning given mining is an increasingly important driver of Amazon deforestation, with more than 1 million square kilometres that could potentially be set aside for mining of gold and other minerals.

We could be facing a race against the clock. The COVID-19 pandemic is driving an economic crisis, and such crises tend to significantly increase the demand for gold, given its perceived role as an economic stabiliser. With gold currently priced at more than US$1,700 per ounce, an increase of 25% so far this year, many small-scale miners are keen to get involved. As environmental laws in Brazil and Venezuela are weakened, this could lead to further deforestation in the Amazon.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.