Henry Moore at the Courtauld Gallery review: a splendid show of the great sculptor's lesser-known drawings

Henry Moore’s drawings are far less well known than his sculpture, and the first thing that strikes you about them is how monumental and sculptural they are.

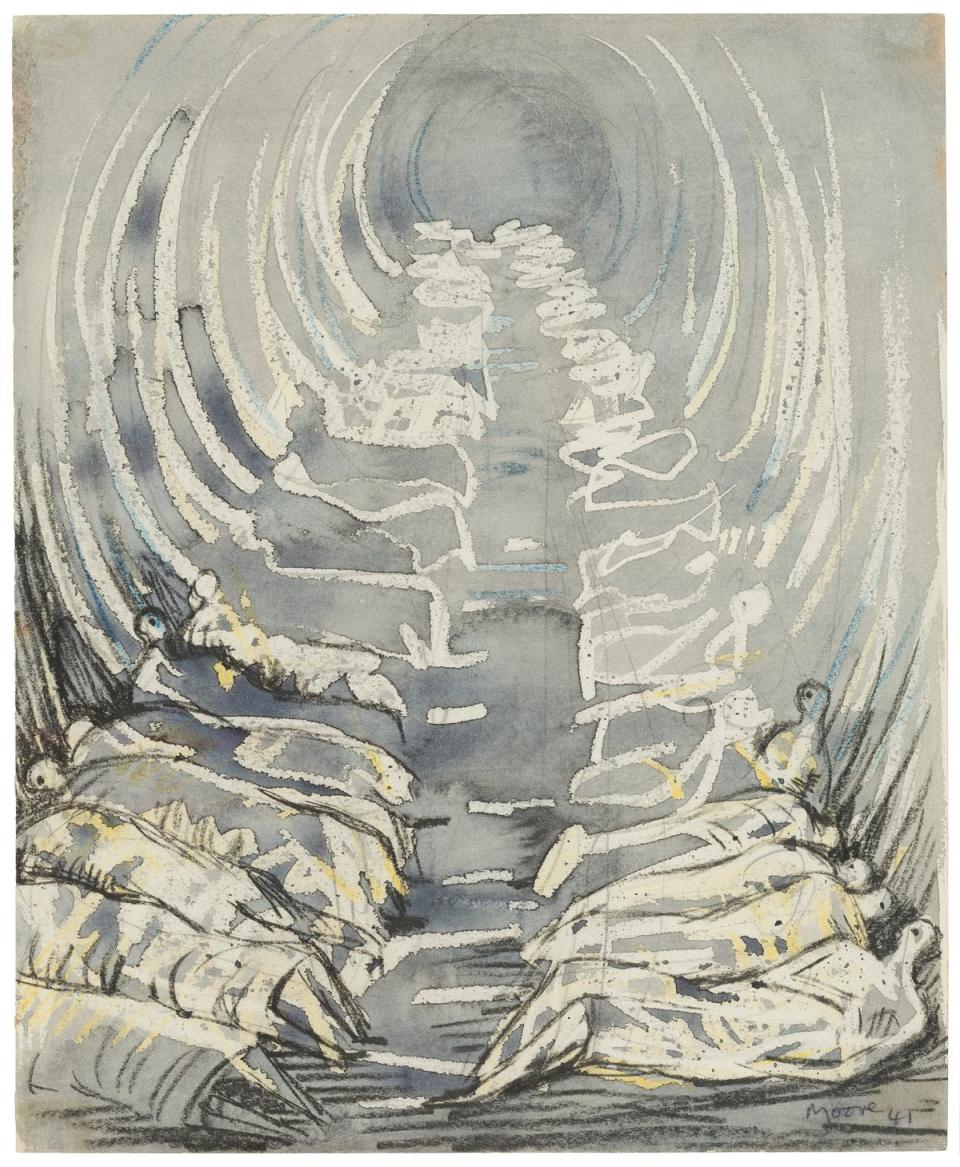

This is true even when he’s drawing people in a particular time and place: in the tunnels of the Underground during the Blitz, in the coalmines of Wales in the war from which Moore made hundreds of sketches from 1940 to 1941. These form the basis of the exhibition.

In one picture, there’s a woman in a hat resting her head wearily against a wall; she could be a 15th century pilgrim – her dress is of no time and place. The individual is undefined but there’s a sense of a ravaged face, a ravaged life, against a ravaged brick wall.

People are sleeping under sheets next to each other; they look like figures on a medieval tomb, awaiting the last Trump (not that one). People lying in rows in the tunnel look like so many little Henry Moore statues, all undifferentiated and immobile but curiously moving.

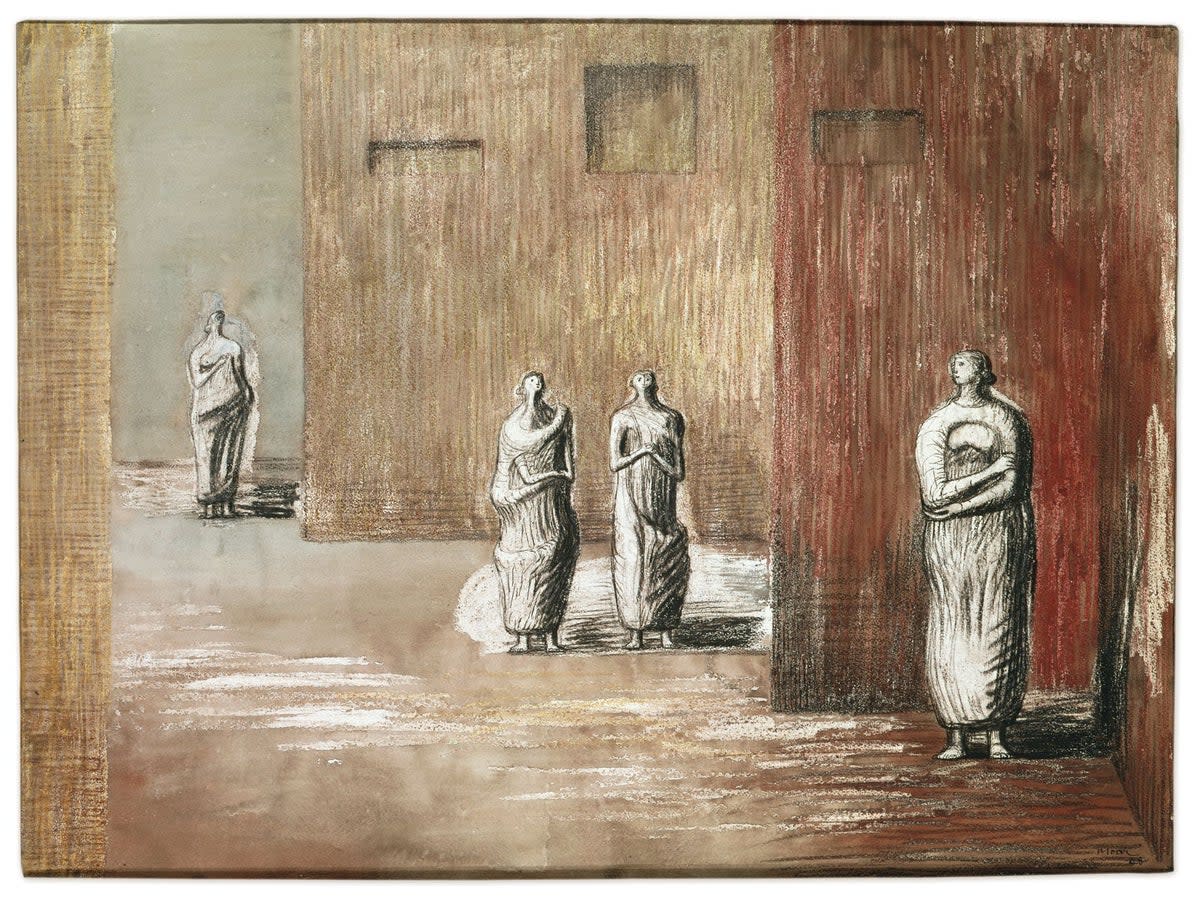

This brilliant little exhibition is called Shadows on a Wall and the title is taken from a play based loosely on the return of Odysseus written for BBC radio by Edward Sackville West with a score by Benjamin Britten (why don’t we have stuff like that now; play it again!) and Moore illustrated the published edition.

You didn’t think he did illustrations, did you? There is a shadow on a wall, drawn by Penelope, that of Odysseus: here ghostly, like a cave painting. The common theme is exactly that – figures and walls, whether tunnels or brick walls, and the exhibition traces how the subterranean work Moore did during the war influenced his work after it. There is an outlier; an interesting commission he did for a Dutch brick factory, which required him to work in brick, an unusual medium. Walls again.

The Blitz tunnel pictures inevitably invite comparisons with, say, Edward Ardizzone, who did the same subject with more human interest. But Moore’s detachment from time and place – though there are details like the bay numbers painted above the shelters at Tilbury which ground it – mean the drawings become as timeless as those of Odysseus.

Courteously, he refrained from drawing people directly in the tunnels, but he made detailed notes and tiny sketches, some of which are reproduced here, and worked them up afterwards. The destruction of his workshop in the Blitz meant less sculpture anyway. Kenneth Clark had deployed him to do the pictures of the Welsh coalmines, where Moore’s father had worked, for a brilliant war artists scheme.

The other artist who comes inexorably to mind with the illustrations and the format is William Blake, but where clarity of line is everything in Blake, Moore’s figures have bulk and depth and repeated lines.

This is a splendid (and free) show which makes us think again about Moore the sculptor.

Also at the Courtauld is a display of work by Vanessa Bell from the gallery’s own fine collection. The centrepiece is A Conversation, her funny, engaging, very female depiction of three women, one of them passing on ripe gossip, the others listening intently, their faces brought up close at the centre of the canvas and much of the rest given over to their coats.

There are also a couple of fine still lifes – an urn against a window, a vase of lilies on a chair, which show just how good she was at this underrated genre. A fine woodcut of A Nude is way more striking than the corresponding painting, reproduced here. And we see her receptivity to contemporary influence in a design of Adam and Eve for a folding screen; Matisse, in this case.

There are some very good designs for rugs from the Omega Workshop, which, as intended by Roger Fry, subsumed the identity of the artist in that of the workshop itself, so we can assume that the pieces are by Vanessa rather than Ducan Grant, but it doesn’t matter.

They demonstrate Fry’s point, which is that the divide between the fine and the applied arts is often pointless. A canvas for a rug is as much a base for design as paper or canvas for paint, and here the limitations of the medium - wool tufts or needlework – is exploited with bold blocks of colour. (Francis Bacon started off designing rugs too.) Vanessa Bell was a versatile artist and some of the fun of her work as well as its originality emerges in this little show.

Henry Moore: Shadows on the Wall is at the Courtauld Gallery, to September 22; courtauld.ac.uk

Vanessa Bell: A Pioneer of Modern Art is at the Courtauld’s Project Space to October 6; courtauld.ac.uk