House’s Covid committee investigation struggles to overcome polarizing politics

The partisan politics that have surrounded the federal and local responses to the Covid-19 pandemic continue to overshadow the committee aimed at examining – and learning from – the government’s response to the disease since the investigation’s start last year.

Rep. Brad Wenstrup, a doctor who chairs the committee looking into the Covid response, told CNN he wants his probe to be nonpartisan, but the Ohio Republican struggles against the polarizing political climate.

Lawmakers on the small panel – the House Oversight Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic – have found glimmers of bipartisanship agreement and even uncovered new insights behind some of the early health guidance, but with hearings devolving into traded barbs, lawmakers are wondering whether apolitical aspirations are possible.

At issue is a fundamental disagreement over how to approach the investigation, which has become a microcosm of the divisive scars left by the deadly pandemic.

Republicans, led by Wenstrup, argue their focus should remain on the origins of Covid-19 and public health officials’ initial guidance – and want to leave former President Donald Trump out of the equation when it comes to finger-pointing.

“I don’t want to get into that,” Wenstrup said when asked by CNN whether the former president played a part in undermining trust in public health officials during the pandemic.

Democrats, guided by Rep. Raul Ruiz of California, who is also a physician, have implored Republicans to investigate equally the possibility that Covid-19 originated from a lab leak or an animal origin and prioritize future preparedness instead of searching for a conspiracy and attacking the scientists and public health officials at the forefront of the nation’s response.

The tug-of-war since the panel’s inception last year has led lawmakers through 27 hearings, 31 transcribed interviews and over 1 million pages of documents, but none of that has gotten them closer to coming together to address the most pressing matter: what can be done differently.

“We can’t allow ourselves in something like this to let politics take over,” Wenstrup, a podiatrist, told CNN during a sit-down interview. “We need to have a group of agnostic people, apolitical people.”

The stakes could not be higher. In the wake of the pandemic, American trust in public health officials has been on the decline and scientific sources have, in many cases, been swapped for echo chambers of misinformation. With rampant vaccine hesitancy, diseases such as measles are now on the rise.

“I set forth to take an objective view of how our nation handled the pandemic to really identify lessons learned for a path forward in order to better prevent and prepare for the next pandemic,” Ruiz told CNN. “It hasn’t been as constructive as it could have been.”

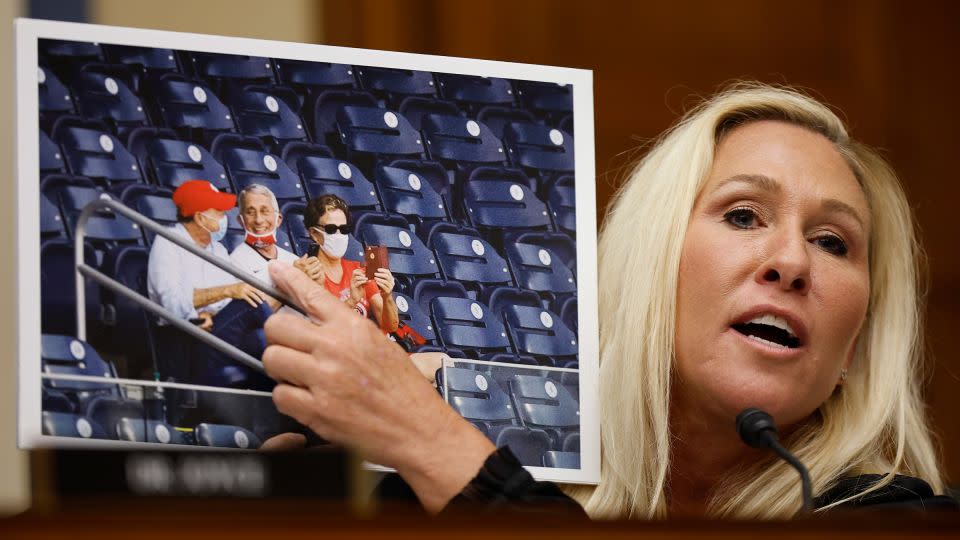

Controversial personalities on the committee have made Wenstrup’s task that much harder. GOP Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, who has espoused numerous Covid conspiracy theories, has looked to vilify several public health officials, but Dr. Anthony Fauci has been her top target. Greene recently refused to even refer to Fauci as a doctor, sending a committee hearing off the rails.

The Republican vilification of Fauci has also largely masked some of the revealing information the former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has shared about his reflections on the early days of the pandemic. In his closed-door interview in January and in public testimony this month, Fauci was candid that the 6-feet social distancing guidance from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “sort of just appeared” and acknowledged that the data on impacts of children’s learning and development due to masks was “up in the air.” But most of that got lost amid lawmaker infighting.

Wenstrup, who is quick to point out that former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries made the committee assignments, doesn’t want to talk about Greene.

“I don’t have time for that because I’m trying to conduct a professional review and do a report,” he told CNN. “And they want to carry on … and anything I have to say isn’t going to stop it. So, I just deal with it.”

But he admitted, “Members of the other side have said to me, ‘You’re doing a great job, you’ve been dealt a tough hand.’ That’s a quote. And one said to me, ‘I wouldn’t want your job.’”

The Trump factor

Republicans insist Trump is not part of the equation when it comes to crafting, as Wenstrup calls it, an “after-action review, lessons learned” of the pandemic.

Wenstrup says he does not want to be drawn into politics and plans to release his final report without political references.

“No matter who said what, Donald Trump, Joe Biden, we can go through a list and point out, ‘Oh, he said this, he said that,’” Wenstrup said. “The point is I want to stay medical and scientific.”

GOP Rep. Marc Molinaro, who led the public health department in his New York county in 2020 and helped the committee prepare for its recent interview with former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, acknowledged that the federal government’s response in the early days of the pandemic was “disorganized” without naming Trump specifically.

But he argued that criticism misses the point.

Molinaro said he doesn’t know whether those who say Trump deserves more blame “understand emergency response in this country.”

“We don’t respond to emergencies, no matter how big they are, starting with the federal government and then go into local governments,” he said. “We start at the local and move our way up.”

Republicans claim Democrats’ focus on Trump’s handling of the pandemic is meant to ignore other components of the response that need addressing.

“We have a tendency to say, ‘Pay no attention to all the crisis, all of the problem, all of the undermining that occurred in states like New York and around the country, look over there, Donald Trump said something we don’t like,’” Molinaro said.

GOP Rep. Ronny Jackson of Texas, who served as Trump’s doctor in his administration and is on the committee, said Democrats don’t acknowledge that the former president launched the operation to rapidly develop and deploy Covid vaccines and instead focus only on his statements they don’t like.

“Democrats aren’t bringing that up,” he said.

But to Democrats, the former president, who made a litany of dubious or inaccurate coronavirus-related medical claims during the pandemic, including at one point dangerously suggesting that ingesting disinfectant could possibly be used to treat the virus, cannot be separated from the committee’s work.

“They do not mention President Trump on their own accord,” Ruiz said.

Moments of bipartisanship

The partisan backdrop hanging over the committee has often clouded breakout moments and glimmers of bipartisanship.

Cuomo told lawmakers behind closed doors this month that it did not matter the way deaths in New York were counted during the pandemic – an astonishing admission from a former official whose career has been defined by his handling of the public health crisis in his state.

“Your obsession on the difference between 6,500 and 9,000 is bizarre because it makes no difference for any purpose,” Cuomo said, according to a portion of the transcript shared with CNN.

“Let’s say there is a 3,000 differential, 2,500. Who cares? What difference does it make in any dimension to anyone about anything?” Cuomo later said, according to the excerpt shared.

The behind-the-scenes testimony about how deaths in New York were categorized, which has not been previously reported, left lawmakers in bipartisan agreement that more investigating needed to be done.

A spokesperson for Cuomo defended the former governor’s testimony, and pointed to his opening statement of the interview.

“The point was there was no discrepancy as all categories were contained in the overall death number, which was never in dispute, but what the Republicans couldn’t explain was why 1.2 million Americans died during this pandemic – more than any other country and any other war – under the lack of leadership from Trump and the Republicans that continues to this day as they put a podiatrist in charge of the COVID committee,” Cuomo spokesperson Rich Azzopardi said in a statement to CNN.

Cuomo has been investigated by the Department of Justice, Manhattan district attorney, New York attorney general and the New York State Assembly, none of which brought charges for his handling of the pandemic.

Arguably the most bipartisan moment from the committee was its probe into a New York-based virus research organization tied to controversy about the origins of the virus that causes Covid-19. The federal government suspended EcoHealth Alliance’s funding in May, as Democrats and Republicans on the committee criticized the behavior of individuals at the organization.

“That’s one of the small, bright, shining moments that this committee had,” Democratic Rep. Deborah Ross of North Carolina, a committee member, told CNN.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have also condemned evidence they uncovered that a former National Institute of Health official deleted emails and tried to get around requirements to disclose information through public records laws — something Fauci called “an aberrancy.”

Why lawmakers think Covid has gotten so political

Lawmakers by and large can pinpoint the need to remove politics from the subject of the pandemic – they just can’t seem to overcome the obstacles.

Wenstrup, an Army Reserve officer and Iraq war veteran, believes politics should be left out of the Covid response equation, like it is with the military.

“I’m military, when I’m in that uniform, politics were out,” Wenstrup said. “That’s what we got to have for this type of thing. And science is science.”

He says his final report will advise that doctors, not politicians, should be the messengers when it comes to public health and that the guidance should be tailored to local communities instead of broad mandates from the federal government.

“Americans don’t do well with ‘Because I told you so,’” Wenstrup said of mask and vaccine mandates.

Ruiz, similarly, believes politics should remain out of the reckoning and has implored his Republican colleagues to stop making extreme accusations, telling CNN, “This should not be about personalities, it should be about pandemic preparedness.”

The question becomes where the disconnect is between identifying the problem and solving it, and that hurdle has huge ramifications.

Wenstrup argued that the pandemic occurring in a presidential year impacted how it was perceived.

“It was a presidential year, and it got so political,” Wenstrup said of 2020. “What should have brought us together like 9/11 became this political football. Since when is a virus a Republican or Democrat? I mean, come on, people.”

Others say politicians not being willing to admit they were wrong in some of their rushed life-or-death decisions has heightened the polarization and public distrust.

“I think it’s really hard for proud, powerful people to acknowledge that they made mistakes. It’s almost as if they have never been married,” Molinaro told CNN.

Ultimately, these dynamics have left the two sides of the committee unable to come together, doing little to restore trust in the public health system.

“I think this committee has lost an enormous opportunity to do bipartisan work to prevent future pandemics and restore public trust in public health,” Ross said. “And that makes me tremendously sad.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com