Idles on missing Gordon Brown, and sobering up: ‘Our old lyrics were not the words of a healthy man’

Outside the taxi window, Paris zooms past. Balconies with their baskets full of hydrangeas; a beige blur of boulangerie windows lined with flakey pastries; the Eiffel Tower. But before long we’ve left this postcard vision for an industrial city of concrete and metal. It’s a fitting change of scene for Idles, who as a band, don’t exactly scream escargot and macarons.

Since releasing their debut Brutalism in 2017, Idles have been on the front line of British rock. That record combined thrumming basslines and punk licks with candid lyrics on topics like austerity, toxic masculinity, mental health, and white privilege. Its blunt force rage at the state of the nation cut through the noise of complaints that rock music is dead. They’ve since earned a spot on the Mercury Prize shortlist, a Brit nomination, two No 1s, several top fives, packed-out Glastonbury sets, and many a sold-out tour, including this current one – hence Paris. “Passion is always our strongest feeling,” says Mark Bowen, the Irish guitarist and soft-spoken foil to frontman Joe Talbot. “I think that’s why we’re often confused with being angry – we’re getting out our internal rage and any kind of masculine bulls***.”

We’re backstage in a wood-panelled room where Bowen and Talbot, the band’s two primary songwriters, have sequestered themselves on a sofa an hour before they’re due on stage. The other Idles, Adam Devonshire (bass), Lee Kiernan (guitar) and Jon Beavis (drums), are downstairs cracking jokes between second servings of roast chicken and mouthfuls of rice pudding. It’s the first time Idles have had catering on tour and the excitement is palpable.

Anger in itself has never been Idles’ modus operandi – nowhere less so than on their latest Tangk, their fifth, which nabbed the band their second No 1, and will likely earn them another Mercury nod later this year. (With any luck, it’ll be their first win.) Tangk siphons that passion into something else equally worthwhile: love. Waltzing pianos and pizzicato strings percolate behind their usual prowling synths and garage rock sound. On songs unironically titled “Gratitude” and “Grace”, Talbot positively croons. The city of love, then, isn’t so incongruous a setting as one might think.

During the making of Tangk, both Talbot and Bowen became dads – a fact that goes a long way to explain their softer sound and perhaps their moods, too – both are on top form, easygoing and open. “Fatherhood has taught me that you can have the same kind of passion in other facets of your being,” Bowen says. “There’s passion in gratitude, passion in tender moments.” Both he and Talbot are determined to do the dad thing “really f***ing well”.

Talbot, who is Welsh and born in Newport, met Devonshire at school in Exeter. It was when the pair moved to Bristol for university that they found Bowen, fresh out of Belfast, on the city’s DJ circuit. Their first EP Welcome, released in 2012, favoured a clean post-punk sound by way of Interpol and Radio 4: a portrait of a very different band to the one I’m speaking with today.

But soon came Brutalism, a breakthrough in the truest sense of the word. People sat up and took notice. It was impossible not to, the album’s humanitarian politics hammered into your skull with all the force of its punishing percussion. It was released in post-Brexit 2017 and never has a band sounded so emblematic of the times; Idles were disillusioned and fed up. Over time, this post-punk quintet have become inseparable from politics. Their music is an urgent plea for something better, or an example of empty posturing – depending on who you ask.

For a band with such strong views, they bristle at being called a quote-unquote political band. “If you allow people to say you’re a political band, they can throw you in the bin,” Bowen says. “They can write you off. Coming at things as a ‘political band’ and smashing that into people’s faces isn’t of interest to us because it wears people down too quickly. It makes them too defensive, especially if they’re of a different opinion to you. Our idea is to shake that person’s hand and say, let’s talk and have a conversation.”

All the same, Tangk still retains plenty of that original Idles aggression – mostly aimed at the current government. “What would you like me to say about them?” Talbot says gamely, broad grin spreading across his face. “Evil bastards. Evil, evil bastards. You won’t print this – but f*** the Tories.” He throws his hands up, exasperated by it all. “I miss Gordon Brown so much, so f***ing much.” If it was up to him, Talbot says, the headline for this piece would be: “I LOVE YOU GORDON BROWN.” I tell him I’ll consider it.

He can’t quite believe the “circus” we’ve found ourselves in. “It’s all there in front of us in black and white,” he says, incredulous. “We had a prime minister who was racist in black and white. The government completely ruined our country… in black and white. It’s all there for us to see.”

What does he think of Keir Starmer? “It’s irrelevant how I feel about him. I don’t think that’s a relevant conversation to be had in modern day politics. We need to be talking about the policies and how to fix the insane circus that has been happening for the last 13 years. It’s not about this person-centred crap. Keir Starmer is the leader. He’s the best person for the job right now.” He scoffs. “Better than Jeremy Corbyn.” Quickly, it’s clear any new fuzzy feelings Talbot has around love and fatherhood have not blunted his political scythe.

Talbot’s candour, though, is never more striking than when it is turned inward. Written following the death of his mother, whom he had cared for during a long illness, Brutalism laid bare his pain. It also disinterred 18 years of on-off substance abuse, a recurring theme in Idles’ discography. His addiction came to a head, however, when he nearly died in a car accident after rounding a corner at 60 miles per hour, getting cut off and smashing into a lamp post. He was high at the time. “If someone else was in the car, they’d be dead 100 per cent,” he says now, matter-of-factly. Trapped in the driver’s seat, Talbot could feel the passenger door crumpled against his side, flimsy like tin foil.

The worst thing about recovery is the meritocracy that comes with it

Joe Talbot

By all accounts, the event should’ve changed his life – or at least got him sober. “You’d think so, wouldn’t you?” Talbot grins. “It wasn’t as steep a learning curve as that, I’m afraid. Not a Hollywood moment like that. There’s a plethora of times where the average person with a weaker stomach would’ve stopped everything that I was doing but unfortunately it took me longer to take accountability. That’s not the only time I’ve almost died and it’s definitely not the only time I’ve nearly ruined my life and other people’s.”

In reality, his brush with death was just one of several junctures on the way to recovery – and not even the most important one at that. “Having a child was way more impactful,” Talbot says (he and his partner previously lost an earlier daughter, Agatha, who died during childbirth). “And the patience and the goodwill of everyone around me. I’m very f***ing grateful they stuck with me, carried me for so long.”

Addiction, he clarifies, was only “one component of my debauchery”. Violence, crime, drugs, alcohol – he is very grateful to be done with all of it now. He catches my eye as it darts across the table, strewn with several green glass bottles. “Those are zero alcohol beers so stop judging me!” he laughs. He has been sober for eight months. “Or nine months, something like that,” he shrugs. “I stopped counting; the worst thing about recovery is the meritocracy that comes with it. It’s good for some people to count, I guess, but I’m not not going to have a glass of wine ever again.”

Accountability is a word that crops up a lot in our conversation, and a big reason why Talbot is where he is today: steady and sober. “I’ve met famous people who are mentally ill because of fame,” Talbot says. “And that’s because they don’t have people around them holding them accountable.”

He pauses, considering for a second whether to forge on. “F*** it,” he mutters and ventures forth. “Kanye West is a good example of this.” In recent years, the rapper has regularly spouted hate speech, making a string of antisemitic remarks on his social media and in podcasts. “To me, I see a boy trapped in a man’s body who misses his mother. I see myself in him sometimes. I see that guy. I was that f***ing ill, I was that f***ing alone, and I was that scared, and I was doing s*** that was toxic – and seemingly insane. It happens when you don’t have strong people around to hold you accountable with grace and with kindness.” He gestures to Bowen, “You’ve done it very well with me, and so has my dad. He doesn’t let me get away with slipping; he lets me know with love.”

Is he nervous himself about fatherhood? In particular about raising kids in the current climate, amid the raging dumpster fire that he and Bowen rail against in their music? “No,” says Talbot. “I’m not scared of what’s to come. I mean, f*** me, my mum didn’t get it right and my dad didn’t get it right, but I always knew that I was safe and loved – and at the end of the day, I hope I haven’t made the world a worse place so what else is there to be afraid of?”

Lyrics mostly come easy to Talbot. As they should, he shrugs: “I’m talking to you now and I know exactly what I’m going to say because I mean it.” Most of Tangk was devised at the mic, cobbled together from whatever came to Talbot in the moment. “F*** the king,” for example, is one such lyric that was front of mind.

There was a time, though, when that wasn’t the case. “I got to a place about two albums in where I was becoming too self-aware,” he says of the band’s 2020 album Ultra Mono. “I became detached.” That record cranked the Idles mentality to 11: they were accused of posturing and placard politics. Pitchfork wrote that Ultra Mono “felt like the work of someone who’d spent a little too much time reading their own press”. Ironically, it was also their most successful record to date.

That car crash is not the only time I’ve almost died

Joe Talbot

“You can hear it in the words,” says Talbot of his state of mind when writing the record. “I’ve always found violence to be a beautiful thing in art – but write those words down and you can see they are not the words of a healthy man. I was scared and lost and angry.” At least it was honest, Bowen interjects. “That’s true,” says Talbot. “I never lie – well apart from ‘Great’ on [the 2018 album] Joy As An Act of Resistance. That song is like a bad haircut, which is why we don’t play it. It’s not me.”

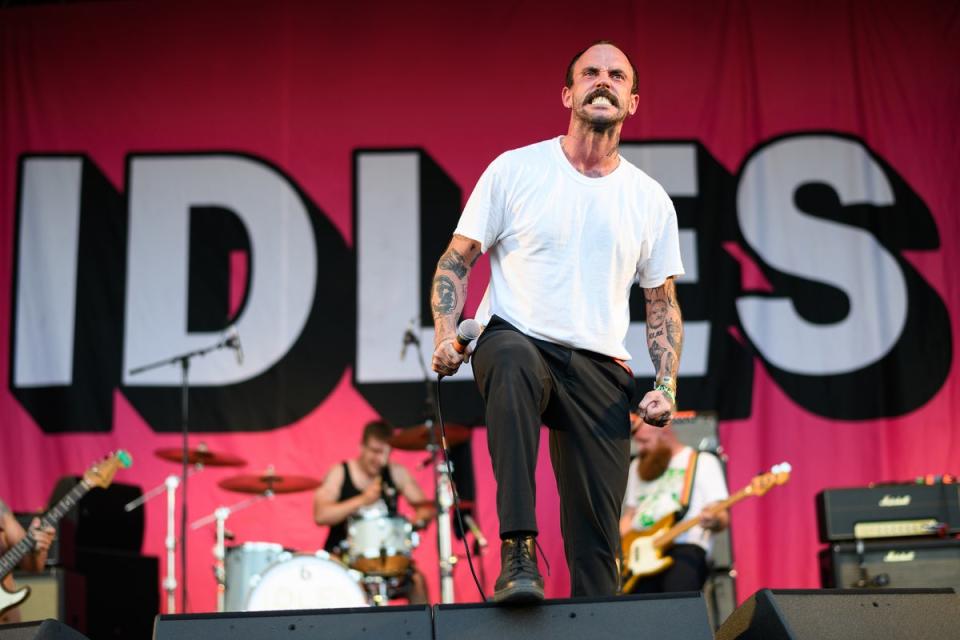

Bowen sees Idles functioning as a “trojan horse” of sorts. “We’re quite a macho, masculine looking band on stage,” he says. It’s true; they are all hairy, sweaty, and inked up. “But we’re trying to subvert concepts of modern masculinity. It’s always about subverting expectations.” In their early song “Samaritans”, he gender-swaps Katy Perry’s “I Kissed a Girl”; during live shows, this lyric is often followed by a big ol’ snog with Bowen on stage.

While they’ve been heralded by some – and ridiculed by others – for their progressive messaging, Idles see themselves as a work in progress. “We’re just processing openly and hopefully that brings people in,” says Bowen. “If you are vulnerable then that often evokes vulnerability.” Talbot adds, “I don’t think we have a ‘responsibility’ other than the responsibility to ourselves.”

He credits their platform with “keeping us aware of things”. The band was recently criticised by fans for their silence about Israel’s ongoing military campaign in Gaza. Tonight, during a hulking, memorable set in Paris, Talbot will scream “Viva Palestina” at the top of his lungs a dozen or so times. “And we should do that because we have a platform and it’s a beautiful feeling to be part of the conversation on the right side,” he says now. “Does it mean we’re going to change the world? No, but I’ve changed my world. And Bowen has changed his.”

You can watch the new video for ‘Pop Pop Pop’ here taken from the album ‘Tangk’ which is out now