Improving migrant workers' conditions must involve every segment of society: experts

SINGAPORE — While the government should take the lead in introducing structural changes, the effort to improve the conditions for migrant workers in Singapore must involve every segment of society here – from direct stakeholders to the everyday Singaporean, said experts.

“All of us have some individual and collective responsibility to do something about it – we can’t just say it’s a government or an evil employer problem,” Associate Professor Walter Theseira, an economist at the Singapore University of Social Sciences, said at an online forum organised by the Institute of Policy Studies on Wednesday (6 May).

The 1.5 hour-long forum touched on the issue of migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, as mass coronavirus outbreaks in their dormitories exposed inadequate living conditions.

“There needs to be that popular will (for the government to embark on change) and a rejection of the ‘trickle-up’ economic model we have where we expect lowly-paid masses to serve us…or else we are not going to get substantial change,” added Prof Theseira, who is also a Nominated Member of Parliament.

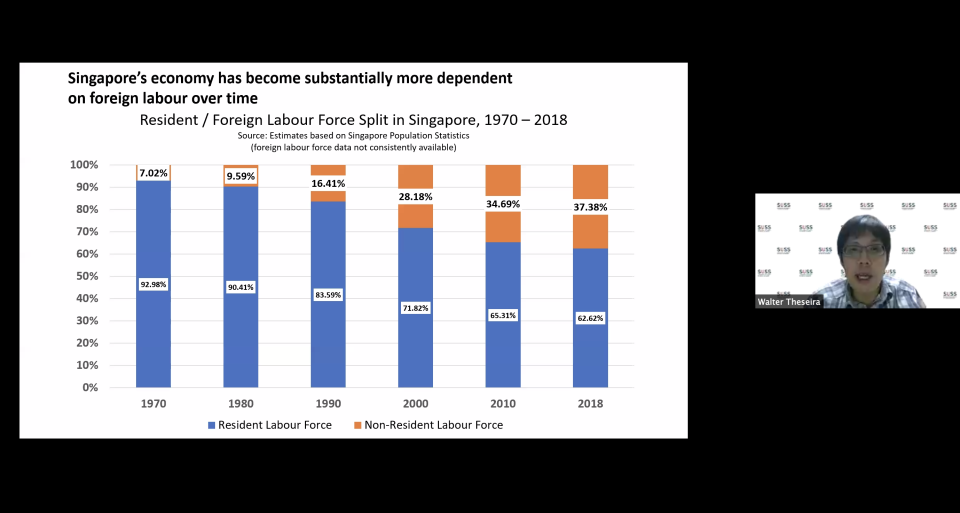

Reliance on migrant workers grown significantly

In his opening remarks, he noted that Singapore’s reliance on such workers had grown significantly over the last 50 years, from comprising around seven per cent of Singapore’s total workforce in the 1970s to some 38 per cent today.

It is “easier to buy rather than make” labour – compounding that, foreign workers here have little bargaining power, with dozens back home willing to replace them, said Prof Theseira.

But if authorities consider implementing higher minimum wages and living conditions, certain migrant labour industries may not be economically viable in Singapore, and that would have “some effects” for Singaporeans as well, he added.

Agreeing, Leonard Lim, country director at political consultancy Vriens & Partners, pointed out that multinational corporations remain attracted to incentives availed to them here if the status quo is kept – such as low business costs – despite their consensus that something must be done for migrant workers.

He added that if Singapore switches to relying less on foreign labour, there will be socio-economic consequences – for instance, public infrastructure like transport and Housing Board flats will take longer time to build.

Associate Professor Jeremy Lim, co-director of global health at the National University of Singapore’s Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, called it “unrealistic” to expect the private sector to do more, given that its primary concern is revenue optimisation, unless they face substantial public pressure.

“I do suspect the migrant worker is so far removed from the end-buyer, and the issues are so complex,” he said. “I do think this is one instance where the government has to show moral leadership and, essentially either directly or through government-linked companies, lead the way.”

Thorough changes unlikely despite strong calls

Because such changes inadvertently have a negative impact on the average Singaporean’s self-interest, the strong call for improvements for migrant workers post-crisis typically does not result in thorough changes, said Prof Theseira.

“That’s the unfortunate reality of it,” he said. “In some way, you can’t expect the average Singaporean to do something against their economic self-interest in this area, any more than you would expect a white American before the civil war to voluntarily abolish slavery.”

Noting that while the comparison is “vastly overblown”, the point remains that there is a large group in Singapore who benefits from such “low-cost labour”, regardless of whether it is of their own volition or not, he added.

“They might not be taking part at all in the bad treatment of migrant workers but by the existence of a society that benefits from low-cost labour, you are benefiting to some extent.”

Prof Lim called the government’s choice to see it as two separate COVID-19 outbreaks here – one in the community and the other in the dormitories – a “defensible” one, from a public health point of view.

But while this served to highlight the different strategies for each group and signal that circuit breaker measures for the “community” have been successful, it “inadvertently further marginalised an already marginalised and vulnerable population”, he noted.

To date, Singapore has 20,939 cases of COVID-19, of which 18,483 are foreign workers living in dorms.

Agreeing, Singapore Management University's (SMU) Associate Professor of Law Eugene Tan called the “constant references” to two different outbreaks worrying, as it perpetuates the mindset that “as long as the Singaporean community is safe, it doesn’t really matter what happens in the dorms”.

“We are addicted to cheap and transient labour,” he said. “As a society, we are not prepared to bear the costs...we are in effect paying the price for the neglect taking place.”

Prof Tan added that the government too has an “important signalling role” to play in shifting the mindset away from focusing on the “economic value” of such foreign workers.

“Looking at the parliament debate on Monday, I was rather concerned that, again, economic value – whether employees are prepared to pay more for dorm accommodation – was really the driving message from the government,” he said.

‘Not in my backyard’ mentality remains

Paulin Straughan, dean of students at SMU’s School of Social Sciences, said that while Singaporeans are “acutely aware” of the difficult living conditions of foreign workers here, they express concerns for their security when these workers move into the same neighbourhood.

For instance, she pointed out that such pronounced fears were left on Member of Parliament Holland-Bukit Timah GRC Christopher de Souza’s Facebook page after he announced that workers from dorms will be shifting into the former Nexus International School at 201 Ulu Pandan Road.

Bernard Menon, executive director of the Migrant Workers’ Centre, termed it “not in my backyard” mentality and described Singaporeans as occasionally “being a little fickle and self-serving” in how they approach the situation.

“We need to depart from that kind of thinking to create a situation where migrant workers don’t need a proxy to assert their rights and entitlements,” he added.

He also noted that public discourse often surged after key crises – such as the SMRT bus drivers strike in 2012 and the Little India riots a year later – but had failed to persist.

“In every crisis, it’s always been my hope that these conversations continue and they persist...but it has lagged behind my expectations,” Menon said.

“We need a platform where we can bring everyone – dorm operators, government officials, employers, activists, and ordinary members of the public – to honestly and openly examine our consciousnesses.”

Hope of rethink on reliance on migrant workers

Nonetheless, there is “some hope” for change as the pandemic may cause authorities to rethink Singapore's reliance on large numbers of migrant workers, said Prof Theseira.

For one, dense cities with high populations are less resilient to diseases and secondly, the propagation of remote working that comes along with the current situation.

Prof Lim also pointed out that the pre-COVID-19 healthcare model for migrant workers – where their employers are responsible for their healthcare – can no longer have a place in crises of such scale and complexity.

“In theory, migrant workers have it very good from a health care point of view. Employers are supposed to fully fund health care, and every migrant worker, every work permit holder is required by law to have some modicum of insurance that covers for hospitalisation,” he said.

In practice, however, the reality on the ground is quite different because of the power dynamics, financial constraints, and the workers’ personal priorities.

“And of course, if we apply the mental model that the migrant workers’ healthcare issues are the responsibility of the employers, then as we transition into COVID-19, it is very clear that the Ministry of Manpower’s responses (as a policy unit issuing directives) have been entirely consistent,” Prof Lim said.

However, he noted that employers and dorm operators have had difficulties simply sticking to the existing regulatory framework, much less with the “overwhelming” additional measures required for COVID-19.

Manpower Minister Josephine Teo had said in Parliament on Monday that almost half of the 43 purpose-built dorms here – where some 200,000 foreign workers live – here breach licensing conditions each year.

To the government’s credit, it quickly “pivoted away” from the model and took over the COVID-19 situation with the military, and the police subsequently roped in, added Prof Lim.

“The policy responses have been guided by the mental model...that we have traditionally taken, is that the migrant workers are part of the community – but they're separate. And we accept that there should be different standards.”

Prof Lim posited, “But the question we then have to pose is if these were not migrant workers and if they were all Singaporeans, would we have no doubt the same plan?”

Stay in the know on-the-go: Join Yahoo Singapore's Telegram channel at http://t.me/YahooSingapore

Related stories:

COVID-19: More Singapore workplaces allowed to re-open gradually, safes measures needed

COVID-19 safeguards in foreign worker dorms 'not sufficient', says Lawrence Wong: report

COVID-19: 2nd reusable mask distribution at end of circuit breaker period – Chan Chun Sing