Inside the Legal Battle Raging Over a Rockefeller Retreat in the Caribbean

Earlier this spring, the scene at the busy beach club at Lovango—the fashionable, three-year-old private island resort in the U.S. Virgin Islands—could have come straight out of a Slim Aarons monograph. There were the glamorously bejeweled guests swirling about in their sand-skimming caftans, taking breaks for the occasional dip in the 70-foot infinity pool. Epic sailing yachts bobbed in the harbor, with skiffs on standby to ferry passengers to shore, where an open-air restaurant beckoned with chilled champagne, ice-cold local beer, lobster guacamole, and $125 tureens of Caribbean bouillabaisse. And everywhere you looked there was Lovango's staff, nimbly attending to all, while simultaneously preparing for a visit the next day by the islands' governor.

Once upon a time—or rather, until September 2017, when category 5 hurricanes Ivan and Maria dealt a one-two punch to the islands—the only place in the USVI to immerse yourself in a scene like this was at Caneel Bay, Laurance Rockefeller’s storied St. John playground for the rich, famous, and social. But for the past seven years, that long-standing resort has languished in hurricane-ravaged ruins, its land inaccessible, its staff laid off, and its future tied up in legal battles between the U.S. government and a real estate investment and management company called CBI Acquisitions.

The dispute is technically over who inherits the right to redevelop the resort, but it’s equally about who gets to inherit Rockefeller’s legacy—one that’s as synonymous with environmental stewardship as it is with luxury hospitality.

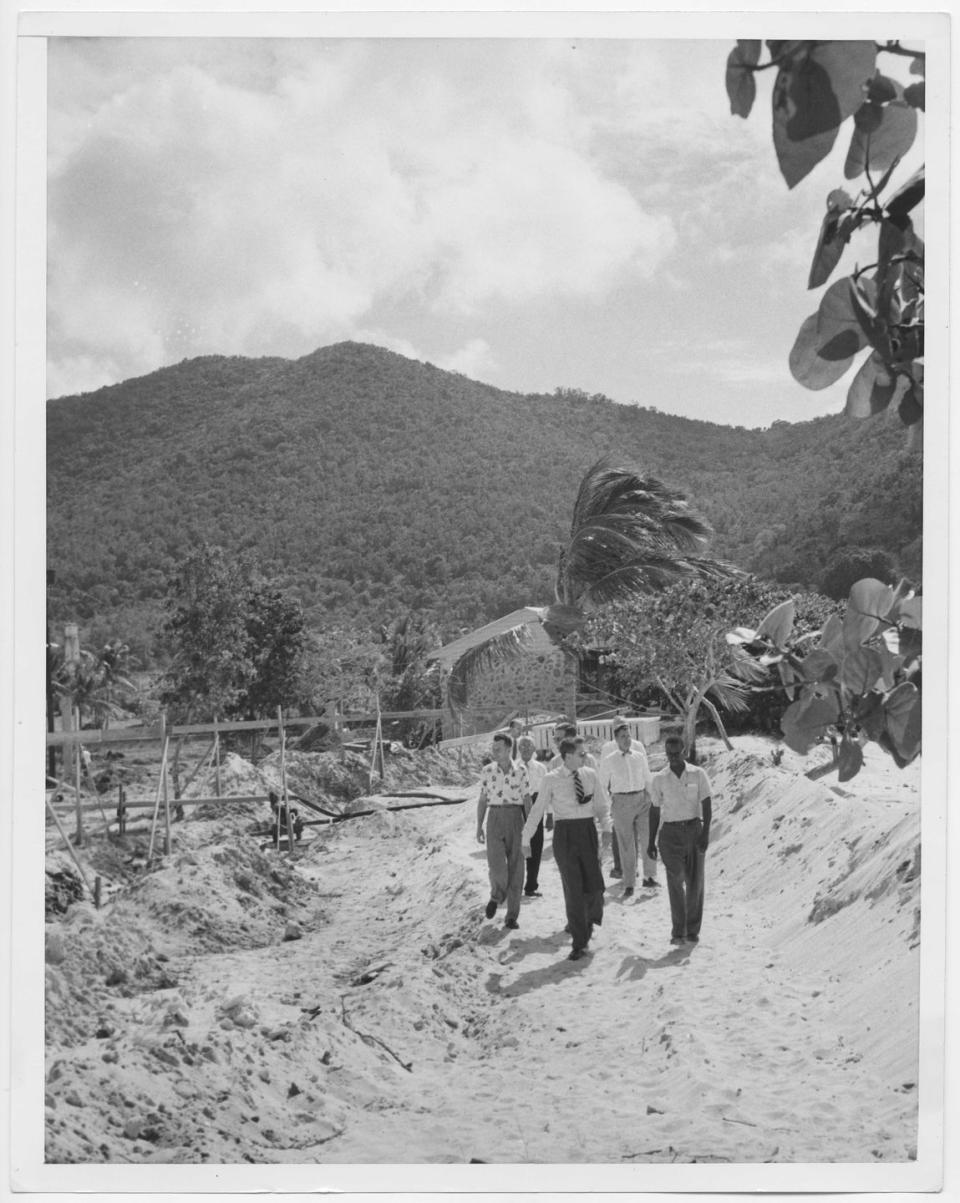

Rockefeller founded Caneel Bay in the mid-1950s, a gem in the midst of the 5,000 acres of pristine land he had bought up on St. John and donated to the U.S. government. That gift gave rise to Virgin Islands National Park, which today comprises 60 percent of the entire island. Rockefeller kept 150 acres for his resort, and in 1983, that parcel became destined for the park’s purview, too, when a 40-year land-use agreement was put in place with the government. In other words, Caneel was to become public property in September 2023.

In its prime, Rockefeller's hotel welcomed a bevy of barefoot-chic regulars paying upwards of $2,000 a night for the privilege of staying in one of its 166 rooms and suites. As recently as March 2017, six months before the hurricanes destroyed it, T&C celebrated Caneel for what author Julia Shingler called its primitive charms. “It's only accessible by ferry or boat,” she wrote, “and as you step onto the dock, you suddenly feel like you're traveling back in time—just as guests like Princess Margaret and Antony Armstrong-Jones did many years before.”

But the resort proved a draw beyond its social cachet, too. “Without realizing it,” Shingler observed, “Rockefeller had become a pioneer of eco-tourism, a concept that was beyond the grasp of many at the time.” People came for the scene, to be sure, but also for the scenery.

“We stayed at Caneel and really loved the naturalness,” recalls Lovango’s Boston-based owner Gwenn Snider, who created her resort, just off the coast of St. John, with her husband, Mark. “It was iconic, and it was in people’s DNA. Guests would return again and again.” That allegiance—plus Caneel’s success as a hotel designed for a well-heeled clientele with an adventurous green streak—convinced the Sniders there was a market for their own eco-chic Lovango.

Today, as Lovango seems to be flourishing, the future of Caneel remains in limbo. In April, a federal judge handed down a decision that finally gave the resort over to the National Parks Service (NPS). EHI, the parent company of CBI Acquisitions, has said it plans to appeal, which could lead to years of further litigation. (EHI and the NPS declined to comment for this article.)

In the meantime, Caneel finds itself at the center of a broader debate over what environmentally conscious and socially responsible hospitality development should look like, especially in beautiful but fragile destinations where tourism supports the economy. “Caneel is a good representation of just how complicated the questions of sustainable tourism are in the 21st century,” says Tonia Lovejoy, executive director of the St. John nonprofit Friends of Virgin Islands National Park, noting the island is home to several species of endangered flora and fauna. “It’s part and parcel of the National Parks System to be in that paradox—preserving and protecting but also allowing safe and responsible enjoyment of these natural resources.”

Of course the larger a resort, the larger its environmental impact—but also the larger the workforce. Caneel was once St. John’s biggest employer. And while a smaller and more exclusive resort means a lighter burden on the land, exclusivity, by definition, limits access. Caneel’s transformation into national parkland would make it accessible to anyone, without the restrictions imposed by corporate gatekeepers, luxury hotel rates, or the price of that Caribbean bouillabaisse.

These paradoxes weighed on the Sniders too. They had been searching for a warm-weather winter destination to complement their two existing hotels—on Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket—when they came upon Lovango in 2019. By then it was a failed real estate project that had sat undeveloped for decades. They immediately fell in love. The hilly, jungled isle had its own coral reef and was just a short boat ride from St. Thomas and St. John. Plus, there was a natural sandy beach that faced an uninhabited bird sanctuary just across a turquoise-blue channel. To the Sniders, it was like a tropical Eden. While crafting Lovango, they made a point to listen to locals, to really understand the community. There was a visceral reaction from everyone they spoke with: Don’t destroy this natural place. The Sniders took that to heart.

Today, 70 percent of off-the-grid Lovango’s electricity comes from solar power, and its 19 accommodations—safari tents, treehouses, and bungalows built with local stone—are tucked into existing foliage to preserve precious plant life. Partnerships with the University of the Virgin Islands have led to hospitality students joining resort staff and to an ongoing reef restoration project. Lovango’s beach club and restaurants, meanwhile, welcome day visitors, increasing access by decreasing financial barriers.

And if you hike up to the top of Lovango, you can just make out the ruins of Rockfeller’s hotel across the water, a bit over a mile away. Since the April ruling, the NPS has begun clean-up at Caneel. While the organization's aim is to balance conservation and access with hospitality development, local sentiment about the proposal, and the community-engagement process surrounding it, remains mixed.

"The National Park didn’t do the due diligence to get residents involved," says one vocal activist, Lorelei Monsanto, a member of the St. John Historical Society’s board. "I am disappointed with where we are."

As for the experiment in high-end, environmentally conscious hospitality that is Lovango, it continues to develop—slowly but surely expanding, figuring out best practices along the way, and trying to find equilibrium between the luxurious and the ecologically and socially responsible. Like the eco-retreats of Costa Rica’s bio reserves and the chic tented camps of Botswana’s Okavango Delta, Lovango could come to serve as an object lesson in what light(er)-on-the-land luxe resort development can look like in the world’s most beautiful and fragile places—not least in the Caribbean, and especially right next door, in the tangled, litigation-challenged wilds of Rockefeller’s Caneel Bay.

“Caneel is so important to the territory as a signature experience,” Lovejoy concludes. “It could define the brand of tourism that is globally promoted and expected from the U.S. Virgin Islands for decades to come. It will set the tone, defining what we talk about when we talk about sustainable tourism here. And it could raise the bar, making us a shining star.”

You Might Also Like