Japan's alienated youth overlooked in elections

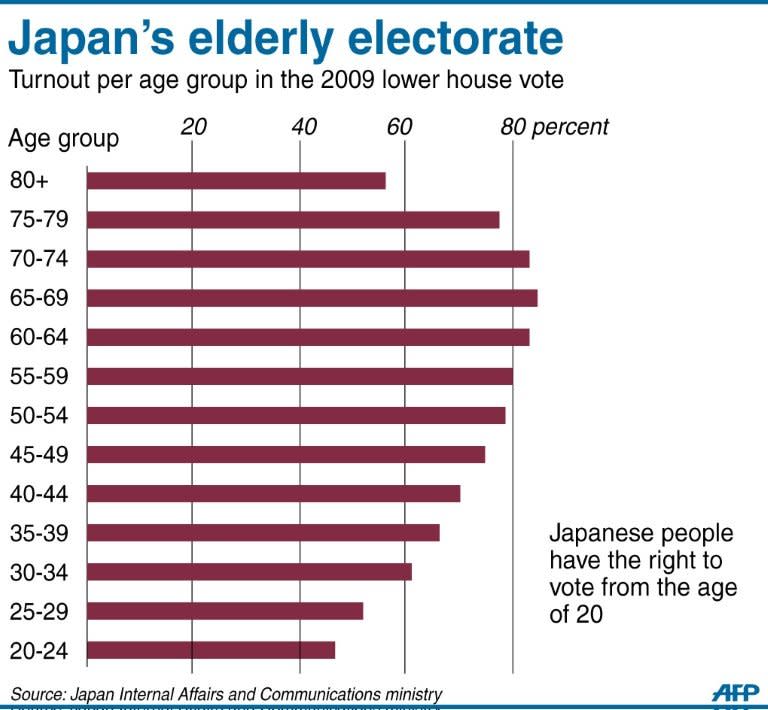

Japan's young people, alienated and outnumbered by a greying population, will barely bother to vote in weekend polls after a campaign that excluded social media and made little effort to engage them. Opinion polls published Friday show the establishment Liberal Democratic Party -- which draws its support largely from Japan's ageing countryside -- well on its way to victory in Sunday's poll. Commentators say that in a nation with one of the world's oldest populations, mainstream parties like the LDP have little incentive to cater to the young. "A single vote will not change anything. Many people think like this, that's why the number of young voters is so low," heavily-pierced 17-year-old Tsukasa Takahashi told AFP. Unlike in the United States where Barack Obama harnessed the power of social media to leapfrog traditional media and speak directly to the young, candidates for office in Japan are barred from campaigning on the platforms. "Young people don't really read newspapers. I don't either, it's a fact," said 20-year-old Shiori Kasukawa. "I think it would be good if (politicians) communicated with social networking sites." Under ballot rules, politicians who have ventured across the digital divide had to freeze their Twitter accounts when the official campaign period began, 13 days before Sunday's vote. Electoral laws treat anything appearing on a screen as akin to a leaflet, and there are limits on how many fliers any candidate can produce. Kazumasa Oguro, associate professor of economics at Hitotsubashi University, says the law is self-reinforcing: present-day parliamentarians got there without the Internet and have no interest in changing the rules. "Frankly, it would disadvantage older policymakers," he said. Calculations based on government figures show the average age of people casting ballots at the last general election was 54.2. And less than half of eligible voters in their 20s went to polling stations in 2009, compared with nearly 85 percent of electors aged in their 60s. The ageing voter profile weighs heavily on policy-making, said think-tank researcher Manabu Shimasawa. "Elderly people have greater impact on election results, so politicians just push for policies preferred by elderly people," he told the Japan Times. This plays out in social security payments, for example, where households of those in their 60s now will be net receivers over the course of their lives, while those not yet in their 20s will be net contributors. "Many systems in Japan are no longer sustainable and are virtually collapsing, but they are not changing," said Ryohey Takahashi, 36, a member of Wakamono (Youth) Manifesto, a lobby group. "What sits behind this is the 'silver democracy', where the voices of the elderly are mostly represented in politics." Before Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda -- a sprightly 54 -- dissolved the lower chamber last month, about a third of its 480 members were over 60. Government figures show this is generous representation for a population where around 23 percent are over 65, a number expected to rise to 40 percent over the next four decades. Wakamono Manifesto argues that money spent on keeping the elderly happy -- such as tax breaks on retirement cash -- should be switched to support workers of child-rearing age. It also urges the government to reform the electoral system to reduce the age of majority to 16 from the present 20, which he hopes would boost participation. "I hope more politicians in their 30s and 40s will have a stronger say in parliament," said 20-year-old Toyo University student Kohei Hirota. "We have very old, slow-speaking lawmakers, who make me wonder if they are really alright." In Tokyo's fashionable Shibuya district, 21-year-old student Michiyo said politicians were unintelligible to people of her generation. "One main reason why we don't vote is that we don't have any information. We don't know what they say at their meetings," she said. "And when they do tell us, we don't really grasp the meaning of what they say."