Judge Orders Kids Removed From Louisiana's Former Death Row

Louisiana has incarcerated dozens of youths in a former death row unit of its infamous Louisiana State Penitentiary, better known as Angola.

UPDATE: Sept. 15 — Louisiana’s Office of Juvenile Justice said in a statement that it transferred all children out of the juvenile facility at the state penitentiary, despite an appellate court temporarily pausing Judge Shelly Dick’s order.

PREVIOUSLY:

A federal judge ordered Louisiana officials to remove incarcerated children from a former death row unit in the infamous Louisiana State Penitentiary by Sept. 15.

Chief District Judge Shelly Dick’s Friday decision followed a seven-day hearing as part of an ongoing lawsuit filed by teens in the custody of Louisiana’s Office of Juvenile Justice. Dick found that the conditions of confinement at the prison — a former slave plantation better known as Angola — amount to cruel and unusual punishment and violate the 14th Amendment, as well as a federal law protecting children with disabilities.

“This is a case of promises made and promises broken,” Dick wrote in her ruling, which enumerated six broken promises relating to the length of time the Angola facility would be in use, the number of kids sent there, and how they would be treated. “Regrettably, the Court bought what the Office of Juvenile Justice was selling.”

“The youth at Angola are being victimized, traumatized, and seriously and irreparably harmed,” Dick continued.

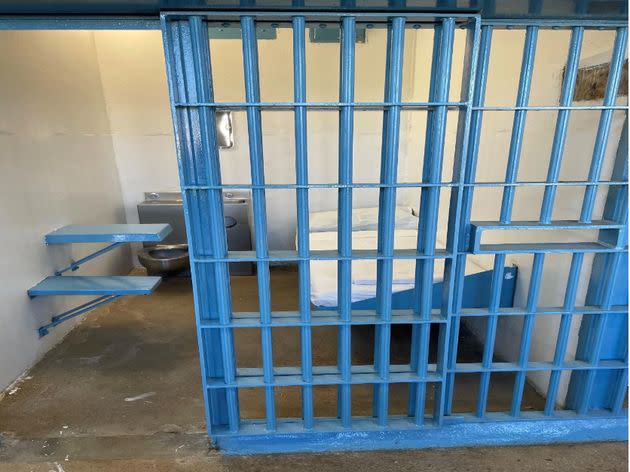

Of the estimated 70 to 80 children who have been incarcerated at the Angola unit, known as Bridge City Center for Youth at West Feliciana or BCCY-WF, the overwhelming majority are Black. The state had previously assured the judge that conditions at BCCY-WF would be comparable to other juvenile facilities in the state, only in a more secure building. However, the children imprisoned at Angola report spending days in solitary confinement in windowless cells, losing access to education and disability accommodations, having limited phone calls and visits with their families, and being physically abused by guards.

“For almost 10 months, children — nearly all Black boys — have been held in abusive conditions of confinement at the former death row of Angola – the nation’s largest adult maximum security prison,” lead counsel David Utter said in a statement. “We are grateful to our clients and their families for their bravery in speaking out and standing up against this cruelty.”

During a hearing last month, Henry Patterson IV, a guard at BCCY-WF, admitted that the kids are kept in “cell restriction” for as long as five or six days. Cell restriction is used at intake, as well as to punish everything from assault to throwing food, graffiti, and destroying clothing, according to evidence presented at the hearing. State law prohibits keeping juveniles in solitary confinement for more than eight hours.

The hearing also exposed a shocking incident in which a guard pepper-sprayed a teen who was locked in his cell and left the boy there for about 14 minutes before removing him from the toxic gas. Guard supervisor Daja McKinley testified that the boy had thrown liquid from his toilet at a guard, who responded by unloading pepper spray into the cell.

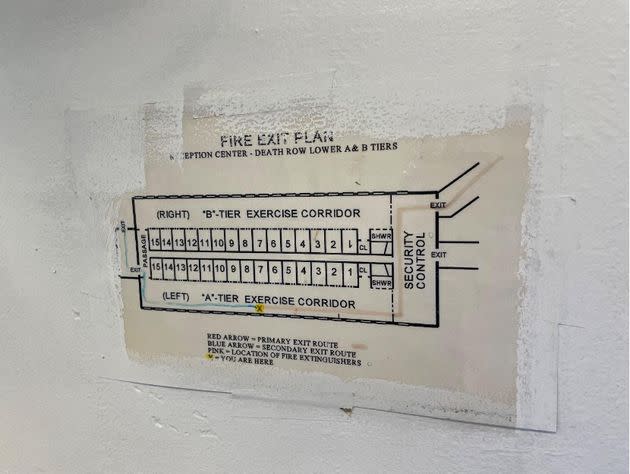

In July 2022, Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards announced a plan to move about 25 kids from OJJ facilities into a building that, until 2006, had imprisoned men on the state’s death row. The governor cited several recent escapes from juvenile facilities as evidence of the need for a more secure facility. Officials claimed that children would only be at Angola temporarily until renovations on a juvenile facility were complete and that they would retain access to rehabilitative and educational services.

Death row signage was removed from the unit shortly before kids started arriving last year.

The proposed transfers faced immediate backlash. Elizabeth Ryan, administrator for the Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, warned OJJ leadership on July 25, 2022, that “the state will potentially be in danger of violating federal laws” and “could potentially face costly litigation.”

Unlike the adult prison system, the juvenile justice system’s explicit purpose is rehabilitation rather than punishment. Juvenile delinquency adjudications are civil findings, not criminal. According to OJJ, youth in their secure custody facilities are housed in dormitories or housing units rather than cells, with an emphasis on treatment and family involvement.

“Every single one of these young people will be released by their 21st birthday at the very latest, and it is Louisiana’s job to ensure that, by that time, they have been educated, treated, and supported in a way that enables them to live healthy lives without posing a risk to the community,” a group of current and former youth correctional administrators wrote in a letter to the governor last year. “Sending them to Angola will do the opposite.”

“Angola is perhaps the most infamous prison in the country, and exists in our national conscience as a quintessential harsh, merciless, and dangerous place for adults who may never be free again,” the group of youth correctional administrators continued. “This lore is not lost on the children that Louisiana is now planning to send there. The stigma and trauma of a move to Angola would be devastating for the mental health and future prospects of these young people and, consequently, the safety of the citizens of Louisiana when these young people return to their communities.”

The Louisiana State Penitentiary, the state’s only maximum-security prison, sits on 18,000 acres of farmland that used to be a plantation called Angola. When the plantation became a prison, the prisoners, rather than the slaves, tended to the fields. Most of the state’s prisoners who are facing life sentences — who are disproportionately Black — are incarcerated at Angola, where jobs include working the fields for pennies an hour.

Weeks after Ryan’s warning, a group of children in OJJ custody sued Edwards and other state officials and asked Judge Dick to block the transfers from proceeding. The children are represented by the ACLU, the Claiborne Firm and Fair Fight Initiative, the Southern Poverty Law Center and the lawyers Chris Murell and David Shanies.

“I am terrified of being moved to Angola,” a 17-year-old plaintiff identified by the alias Alex A. wrote in a declaration last year. “Ever since I learned we were going to be moved, my sleeping troubles have gotten worse. I would lay awake at night and start pulling on my hair until it came out.”

Alex A., who has a disability, expressed fears that he would lose access to schooling, counseling and calls with his mom — “the part of the day I look forward to the most,” he wrote.

Last September, Dick allowed the transfers to proceed while the underlying case moved forward. She acknowledged that being in Angola would “likely cause psychological trauma and harm” to the children but expressed confidence in OJJ’s assurances that the facility at Angola would be comparable to other juvenile facilities.

“Plaintiff’s argument that special education services and mental health services will be unavailable or deficient at [Angola] went unproven,” Dick wrote ahead of the transfers.

I am close to getting my HISET (high school diploma) – and it makes me sad I can’t earn it. They keep promising that they’ll give me education, but don’t.a plaintiff identified by the alias Charles C.

The first group of youth were transferred to Angola in October 2022. Their experiences were everything they feared.

“This is much worse than the other facilities,” a 15-year-old plaintiff identified by the alias Daniel D. wrote in a declaration filed in January.

Daniel D. reported seeing mold in the tap of the sink his drinking water came out of and losing power when it rained. His substance abuse counseling ceased when he got to Angola, he wrote, and he was typically locked in his cell alone overnight from 5 p.m. until 6:45 a.m. Sometimes the children would be locked in their cells for days at a time, allowed out only to shower.

The United Nations’ Mandela Rules, outlining the “standard minimum” of humane treatment for prisoners, state that solitary confinement, defined as isolated confinement for 22 hours or more a day, should only be used “as a last resort, for as short a time as possible and subject to independent review.”

Although the children at Angola are in OJJ custody, guards from Louisiana’s Department of Corrections work at the facility, too. “When DOC guards arrive, all OJJ staff say the situation is out of their hands and whatever DOC says goes,” Daniel D. wrote.

One time, Daniel D. wrote, staff — it’s unclear whether OJJ or DOC — allegedly maced a group of kids after one boy struck a guard. Staff put the boy on the ground and punched him while he was being maced, Daniel D. wrote.

In June, during his third stint at Angola, Daniel D. wrote that there was no air conditioner on his block and that when the power went out, they couldn’t even use fans. That month, temperatures reached 99 degrees at Angola.

A 16-year-old plaintiff identified as Frank F. described in a declaration how he was left alone in his cell from 4 p.m. to 8 a.m each day, losing his disability accommodation, losing group therapy, having inconsistent access to hot water, limited access to the phone to call his family and not being allowed outside for recreation on the weekends.

“This is the worst OJJ facility I have been in,” he wrote.

Several of the plaintiffs reported having one teacher for all of the kids and no library. “The last time I was provided access to ‘school’ — a computer, no teacher — was last Tuesday,” a plaintiff identified as Charles C. wrote the following Tuesday, on July 11. “I am close to getting my HISET (high school diploma) ― and it makes me sad I can’t earn it. They keep promising that they’ll give me education, but don’t.”

In that same declaration, Charles C. alleged frequent abuse by staff. The previous week, he wrote, a staff member threw him against a wall, causing the skin on his back to break, possibly from glass. The next day, staff maced a youth in the neighboring cell while the child was handcuffed and shackled, Charles C. wrote. The mace spread into Charles C.’s cell, burning his open wound.

Despite the state’s claims that the Angola facility was not intended to be punitive, several kids said staff threatened to send them to Angola if they misbehaved.

In response to a detailed list of questions, OJJ spokesperson Nicolette Gordon described “a spread of misinformation” and referred HuffPost to an FAQ published on its website. In the FAQ, OJJ claims that the juvenile facility at Angola is fully air-conditioned, that youth have access to “clean and safe drinking water” and that they are “never placed in solitary confinement.”

The FAQ also notes that “there are windows along the full length of each wing where youths’ rooms are located.” Asked if the actual cells are windowless, as the plaintiffs allege, Gordon did not respond.

Pressed about the plaintiffs’ allegations of physical abuse, Gordon said that OJJ does not comment on specific allegations related to pending litigation.

In July, the group of teens in OJJ custody filed a motion asking the court to order the state to remove the kids from Angola.

“The state’s treatment of kids in Angola has been a series of broken promises,” Utter said at the time.

“The state promised the Angola facility would close in the spring. The state promised the kids wouldn’t be held in solitary. The state promised the kids would receive their education and treatment,” Utter said. “None of this has come to pass.”