Kunsthalle Praha chronicles pioneering Bauhaus photographer Lucia Moholy's lost legacy

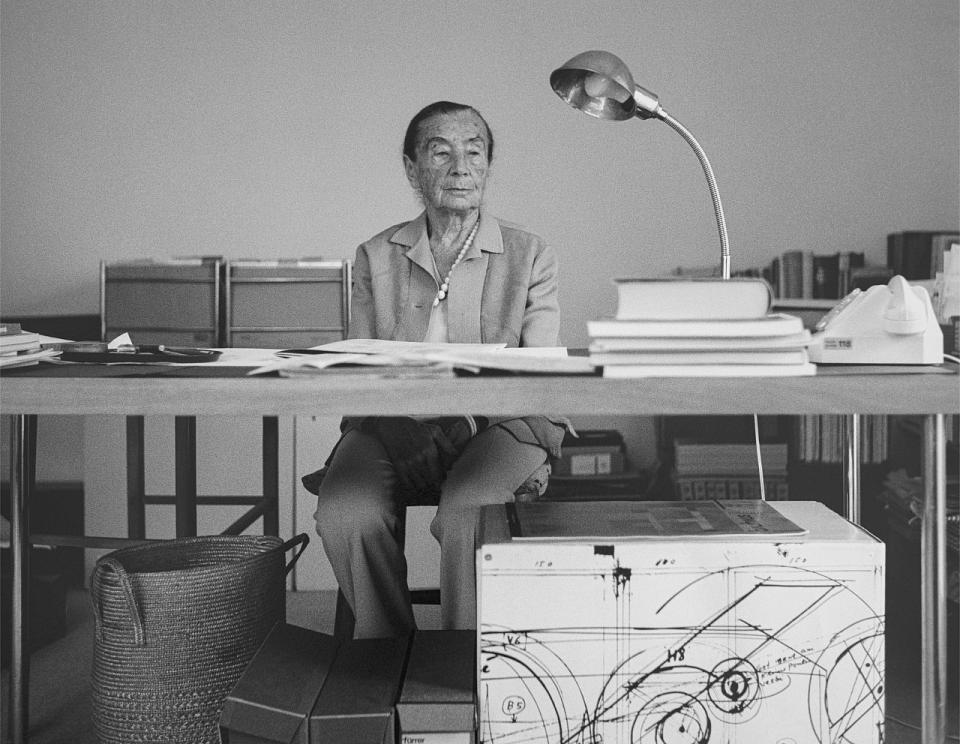

Despite being a pioneering force in photography and visual documentation in the early 20th century, and with her images still seen around the world today, the name Lucia Moholy remains unfamiliar to most.

Perhaps it was because she, like many of her female contemporaries, was constantly overshadowed by the men around her, including her then-husband, László Moholy-Nagy. Or it might be because she was forced to leave behind her invaluable glass negatives of the influential Bauhaus institution when she fled Nazi Germany in 1933. Or because many of her images were reproduced and published without due credit.

But now, her life and legacy are finally receiving the recognition they deserve. The Kunsthalle Praha museum is hosting the first major retrospective of her life, spanning her entire career from the 1910s to the 1970s.

Bringing together years of rigorous academic research and creative effort, 'Lucia Moholy: Exposures' presents more than 600 photographs, microfilms, letters, articles, books, and audio interviews, many previously unseen.

It covers all facets of her work and life, revealing an extraordinary story of a woman who shaped contemporary visual culture against the backdrop of some of the most turbulent times in modern history.

The Bauhaus years

Born in Prague as Lucie Schulz in 1894, Moholy grew up in a Czech-German-Jewish household. She moved to Germany during World War I, where she met pioneering Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy, whom she would marry in 1921.

From 1923 to 1928, Moholy documented the architecture and products of the Bauhaus, one of the most influential art schools of the 20th century that helped shape modern design and architecture.

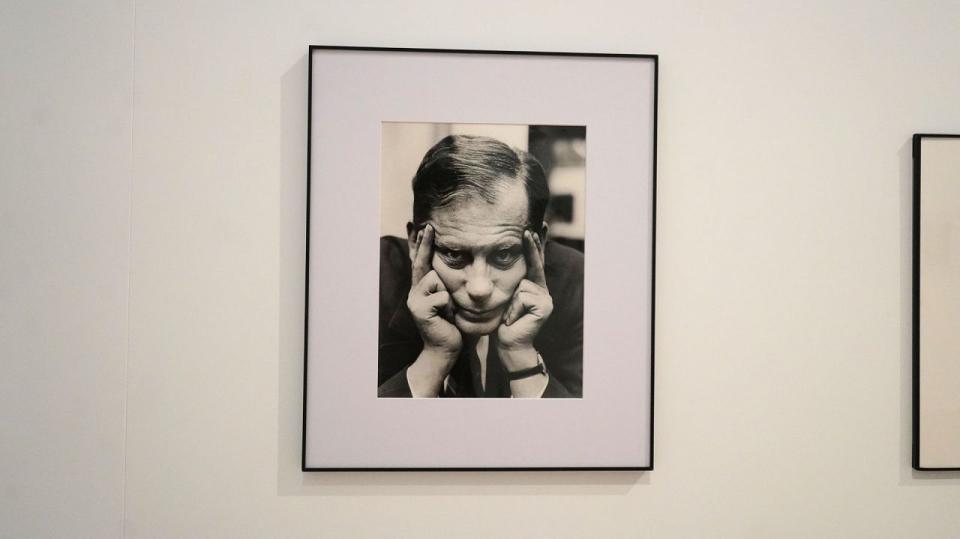

She photographed its buildings, design objects and notable figures, including its founder Walter Gropius, surrealist Florence Henri, textile artist Otti Berger, and her husband, many of which are on display at the exhibition.

Thanks in part to Moholy's meticulous documentation, Bauhaus became renowned for its design philosophy, which sought to integrate individual artistic vision with the principles of mass production and a focus on functionality.

However, despite her vital contributions, Moholy received little recognition for her work throughout her life. Many of her photographs were lost, and numerous others were published without proper credit.

Reflecting on Moholy's lost negatives

Addressing the missing works in Moholy’s oeuvre, 'Lucia Moholy: Exposures' incorporates installations by contemporary Czech artist Jan Tichy, who also helped curate the show.

“Though belonging to different generations, Tichy and Moholy share many characteristics: both grew up in Prague; both experience a life divided between several countries; both experimentally approach the photographic medium,’ says Christelle Havranek, chief curator at Kunsthalle Praha.

One of Tichy’s most poignant works on display is titled Installation no. 30 (Lucia), which he created in Berlin, in 2016. It consists of a video projection on 330 glass plates arranged on the floor, creating an evocative interplay of reflections and shapes.

Since Moholy was of Jewish descent and, after separating from László in 1929, had been married to a communist member of the Reichstag and later a resistance fighter, she fled Germany in 1933, shortly after Adolf Hitler's rise to power.

In doing so, she was forced to leave her entire collection of negatives - fragile and heavy glass plates - behind. Initially, they remained in the care of her ex-husband, who passed them on to Walter Gropius when he fled Germany. Moholy's efforts to retrieve her negatives in England were unsuccessful, and she believed her work from before 1933 was lost forever.

After the war, many of her pictures began to be circulated without attribution, including in prominent publications such as an exhibition catalogue published by The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Only many years later did she recover some of her negatives after lengthy legal negotiations, which she described as a "shattering experience". To this day, approximately 330 of her glass plate negatives remain lost.

Tichy explains: “As I was thinking and contemplating about this story, outside on the street in 2016 there were over a million migrants coming from North Africa, the Middle East. And so for me, Lucia was a way to acknowledge what’s happening in Europe at the moment,” explains Tichy.

Moholy's travel around the world

While Moholy is mainly known within small circles for her work in Germany, Havranek emphasises, "she did much more than being part of the Bauhaus. She had a life before, a life after, and it’s this extraordinary life, full of curiosity about different topics and technologies, that we wanted to present."

Beyond her contributions to Bauhaus, the exhibition highlights Moholy’s extensive travels and achievements. She lived in Paris and London, where she opened a portrait studio and photographed members of the Bloomsbury Group and other prominent artists. She also wrote the first mass-market cultural history of photography, A Hundred Years of Photography 1839-1939, published in 1939.

After her studio was destroyed during the bombing of London in 1940, Moholy pivoted her focus to the emerging field of microfilm technology. Working from the V&A Museum as the director of the Aslib Microfilm Service, she copied smuggled German scientific publications for Britain's strategic use in the war and also devised a method for projecting text for bedridden soldiers to read, an innovation represented in the exhibition by another of Tichy’s installations.

“She was as active in avant-garde circles as she was in the field of information science, advancing an expansive understanding of visual representation,” states the exhibition's catalogue.

Moholy’s journey continued after World War II, as UNESCO appointed her to document the cultural heritage of the Near and Middle East.

Her story is one of resilience, creativity, and a relentless pursuit of artistic freedom. Reflecting on Moholy's life, Havranek says: “This story is about resilience, about not accepting rejection because of your gender or assumptions that you’re not allowed to do certain things, like being in charge of technologies. She always tried to do what she wanted; in a way, it’s about freedom too."

'Lucia Moholy: Exposures' runs at the Kunsthalle Praha until 28 October 2024.