Litman: Trump's fraud trial strategy may be politically effective. But it's legally disastrous

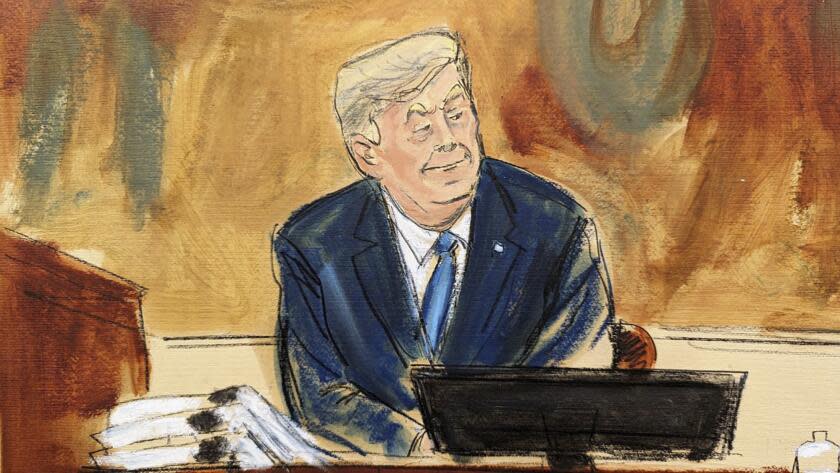

Exasperated by Donald Trump’s nonresponsive monologues during testimony in his New York fraud trial this week, state Supreme Court Justice Arthur Engoron finally told the former president’s lawyer to rein him in. “This is not a political rally,” the judge said. “This is a courtroom.”

Engoron, however, was mistaken. It was a courtroom and a political rally.

Trump turned his time on the stand into a tub-thumping recitation of the themes he hopes will carry him into a second term: that the deep state is persecuting him for his popularity and his election would constitute retribution for him and his supporters.

Trump’s testimony was first and foremost a high-stakes legal showdown in a civil case that threatens to impoverish his family and decimate their brand. And from a legal vantage point, he was routed.

Read more: Litman: Here's Trump's outlandish and dangerous plan to beat the classified documents case

The judge has already found in favor of New York Atty. Gen. Letitia James that Trump and his company committed fraud. The fight now centers on the extent of the Trumps’ liability for a series of comically inflated valuations of their properties, chiefly to secure loans.

Trump’s testimony included a series of damaging admissions within a dust cloud of attacks on the judge, the attorney general and the entire process. It scored many important legal points for James and none for Trump.

Wednesday’s appearance by his daughter Ivanka was by contrast largely polite and professional. She did help set up James' claim that her father misrepresented his personal wealth to secure lower interest rates, but her testimony might have seemed uneventful to someone wandering into the courtroom.

Read more: Litman: What makes the Georgia indictment of Donald Trump so different from all the others

Not so the elder Trump. In response to questioning by state attorney Kevin Wallace earlier this week, he acknowledged more than once that he had reduced the valuation of assets such as his Westchester County, N.Y., estate that he considered “too high.” He also conceded that he tended to look at valuations more broadly: “I would see them, and I would maybe on occasion have some suggestions.”

And he copped to inaccuracies in the statements, for example the ridiculous valuation of his Trump Tower apartment, which was based on square footage nearly three times its actual size.

Trump also acknowledged understanding that the financial valuations he signed were meant to secure loans.

You can bet that Engoron will highlight these admissions as demonstrating that Trump knew the valuations he signed were false.

Trump did interject a few homegrown supposed defenses, either unaware of or indifferent to their legal irrelevance.

He insisted, for example, that because the Trump Organization repaid the loans, “there was no victim.” That’s a nonstarter as a defense because the charge of knowingly submitting false valuations doesn’t require the banks to have lost money. The important point is that the false statements enabled Trump to get better terms.

Expert testimony earlier in the trial suggested the company’s lies saved it $168 million in interest. Look for Engoron to order Trump’s company to disgorge that and more.

Trump’s second ace, or so he thought, was a fine-print disclaimer that banks should not rely on the company’s estimates. Trump even had a copy of the clause in his vest pocket that he tried to pull out on the stand. But the argument misses the mark for the same reason: It’s not relevant to the charge of knowingly submitting false valuations.

The judge sharply dismissed it: “No, no, no. We are not going to hear about the disclaimer clause. If you want to know about the disclaimer clause, read my opinion again — or for the first time, perhaps.”

“Well, you are wrong on the opinion,” Trump replied with characteristic arrogance. It was one of a series of insults of a judge who is authorized to make determinations about Trump’s credibility. That makes the former president’s puerile attacks on Engoron a kamikaze mission.

Legally, Trump began in a hole and proceed to dig straight downward. Almost every observer of the trial anticipates a verdict that will be devastating to Trump and very possibly eviscerate what remains of his business empire.

And yet there’s no getting around the sense that not only did Trump bring this legal harm on himself, he did so on purpose.

Consider the bitter diatribes he spewed at various targets at spontaneous intervals. He told Wallace, the state attorney, that he should be ashamed of himself; he pointed to James and screamed, “The fraud is her!”; he proclaimed, “This is a very unfair trial. Very, very.”

He ranted and raved in a way that would have landed many other witnesses in handcuffs. But Engoron by and large let it go, cautious not to take the bait and create an issue on appeal. And Wallace was content to let Trump rail away for the nuggets of damning testimony embedded in his raging.

I am not one of those who believe in Trump’s secret strategic genius, and I don’t see his unhinged fulminations as a calculated political masterstroke. But the whole spectacle was the clearest illustration to date of the most bizarre feature of Trump’s legal troubles: Every motion, every testimony, every legal theory is wholly political — a political rally in a courtroom.

Trump is a one-trick pony whose approach to every situation is the same toxic brew of grievance, vanity and hate. His legal strategy is identical to his political strategy.

We can expect him to have even worse legal days as he confronts ever more serious threats to his fortune and liberty. We can count on him to continue to respond in ways that harm his legal prospects but delight his followers as he seeks to make a joke of the legal system. We can only hope that the system has the last laugh.

Harry Litman is the host of the “Talking Feds” podcast. @harrylitman

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.