‘Masters of the Air’ Artisans on Building B-17s Bombers to Flight Uniforms to Bring Authenticity to World War II Drama

Oscar-winning costume designer Colleen Atwood had to make between 200 and 300 leather bomber jackets for AppleTV+’s World War II series “Masters of the Air.”

Despite having more than 80 credits to her name, Atwood had never done a WWII drama and was delighted to finally be tackling the era. She dove deep into researching the period, collecting photos of the young men on the military bases so she could create individual styles for the actors and their characters. She even got samples of the original uniforms.

More from Variety

Don't Forget About: 'Masters of the Air' Stars Nate Mann and Anthony Boyle This Emmys Season

From 'We Were the Lucky Ones' to 'Masters of the Air,' Inside the Rise of World War II TV Shows

Her biggest challenge, however, was recreating aviator jackets of the era. It took her six months to complete the task, which ended up becoming a global undertaking.

Leather specialist Gary Eastman provided Atwood with the material, but she needed period-specific zippers, which she had shipped in from Japan. The sheepskin for the shearling linings came from

Scotland and England.

“We had to shave the inside of the jacket, so it wasn’t as thick. Otherwise, they’d look like the Michelin man,” Atwood explains. To make sure the jackets looked appropriately worn, “We put them in a cement mixer with a vat of rocks to beat up the leather.”

The large ensemble cast features Austin Butler as Maj. Gale “Buck” Cleven, Callum Turner as Maj.

John “Bucky” Egan, Anthony Boyle as Lt. Harry Crosby and Barry Keoghan as Lt. Curtis Biddick as U.S. bomber pilots based in the U.K. who fly dangerous missions targeting key positions in German-occupied Europe.

Atwood gave each character a different jumpsuit to reflect their styles. She based Butler’s character’s style on the real-life Cleven. “Cleven wore a scarf a lot. He was a little bit more flamboyant and very pulled together,” she says.

“We used an original flight suit, and he had a beautiful chocolate brown suit and handmade ties and his lightweight leather jacket,” she says. “That was his signature look with the scarf. He had a specific watch and glasses.”

In some cases, Atwood was able to source genuine material from the era. “Those are original masks, but I had to repurpose them and refit them,” she points out. “I kept finding ways to make them smaller so you could see the actors’ faces.”

Atwood also had to make lots of insignia patches and medals for on-screen talent, manufacturing

them from metal because “I needed them in such huge quantities.” On some days, there were more than 300 extras.

While “Masters of the Air” leaned into male characters, Atwood had to create designs for female characters who worked on the base or interacted with the crew, whether in London clubs or rural

villages behind enemy lines. Bel Powley’s character, Sandra Westgate, is a spy. In one scene, she’s an art dealer whose Paris store is a front for espionage

Director Dee Rees wanted Powley to pop in the environment, so Atwood came back with a blue

coat. Her fuchsia dress is an homage to Atwood’s grandmother’s wedding dress since she married at that time.

“The shoes are a reproduction. We couldn’t use things all the time in those ways because of the size of people now compared to then,” she says. “But we tried to be as honest and honor the period as much as we could.”

Historical correctness was also key for production designer Chris Seagers.

It began with the B-17 planes. While there are still B-17s being flown at air shows, using them would not be safe or practical in the production.

Seagers realized very quickly he would have to build planes to use. “But what did we build?” he says, noting that recreating actual planes “would cost millions, and did we have time?” he asks. He ended up constructing two that would come apart at the nose, the cockpit and the bomb bay for filming. “We made it so those would slide off the gimbal, and you could take any piece you wanted to film with the tiniest of cameras,” says Seagers. “Those two planes ended up representing 50 planes in the end.”

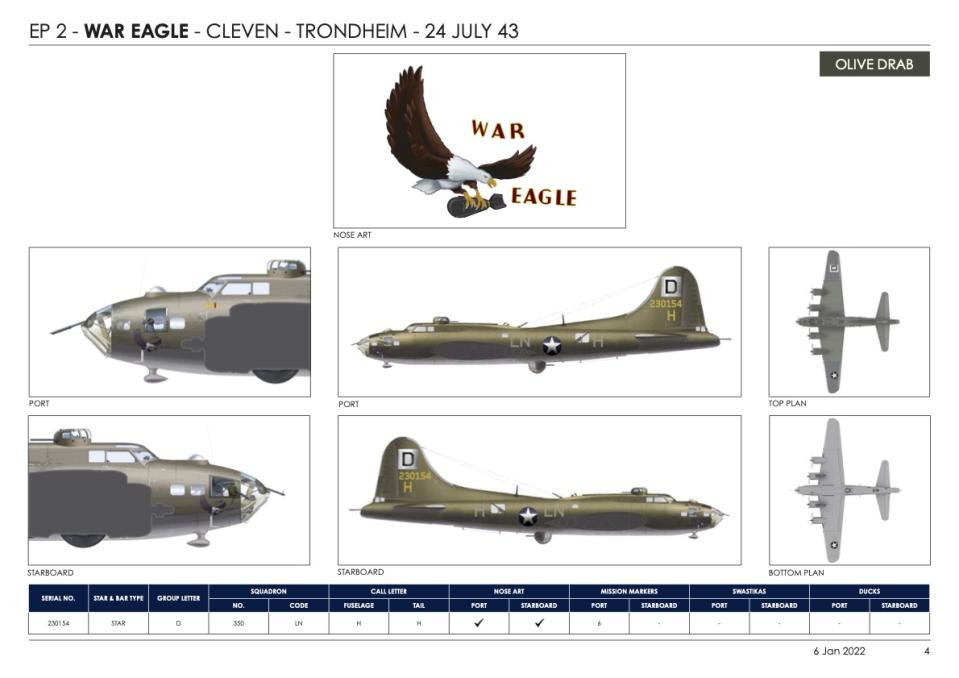

He kept a plane bible to track which ones went on missions and got destroyed but tailored each

one to a specific pilot and mission.

Numerous barracks around the U.K., such as RAF Abingdon in Oxfordshire, were used for ancillary

shots. Originally, producers intended to shoot the series around Europe, but COVID changed that plan. “We used the old runway there, and that’s where we did the control tower,” says Seagers. “We built the admin base, barracks and mess hall — the service side was all built at Newland Park. We found an old runway at the RAF Abingdon station in Oxfordshire for the taxiing shots and to stage the control tower.”

CGI was used to seamlessly stitch together the various locations to make it appear as one.

Not being able to go on location also posed a problem for Seagers for the prison camp scenes,

which are featured in numerous episodes. All the while, he needed to keep them looking real. “They were an expensive thing to build, so we ended up building one camp and we kept turning it around using different treatments on them to make them look different,” he says.

His biggest challenge was figuring out which actor was which and being able to distinguish them when they were in their bomber jackets and helmets. “I’d worked with Colleen before and we discussed it,” he says. “What helped was each had a different color jacket, and that helped, and yes, it was historically correct.”

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.