Milli Vanilli was tanked by an infamous lip sync scandal. Then the rules of music changed.

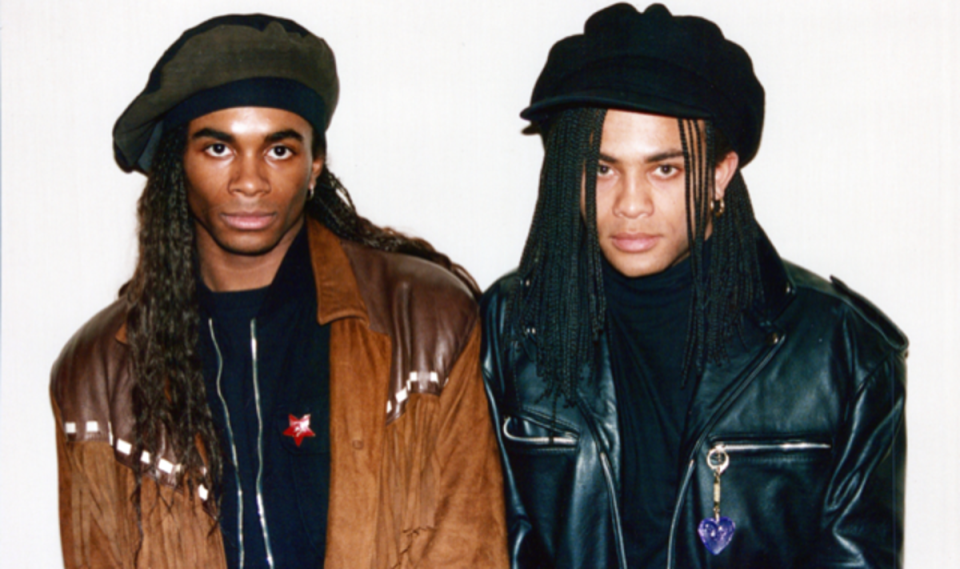

Milli Vanilli burst onto the global music stage in super-tight tights, dramatic long braids and flashy dance moves, a perfect fit for the burgeoning universe of music videos and MTV.

They became a phenomenon before becoming a punchline, the act’s best-selling songs later marred by revelations of fraud, shame and a revoked Grammy.

A new documentary on Paramount+, premiering Tuesday, examines how the world turned on Rob Pilatus and Fabrice Morvan after revelations that the vocals they loved did not match the faces they knew.

To add insult to injury, pop culture evolved to now embrace and glamorise lip syncing; through the lens of TikTok, Ru Paul’s Drag Race, and Lip Sync Battle generation, the duo’s unfortunate musical trajectory seems all the more regrettable.

“They’re being celebrated for being the best lip syncer … but we were crucified,” Morvan tells The Independent. “And it was dark – it got really dark.”

Pilatus tragically suffered with addiction after the public fallout and died at the tender age of 32.

Milli Vanilli director Luke Korem – who was a child at the time of the performers’ fall from grace – marvels at the about-face of the music industry and its fans, and said in early screenings young people couldn’t comprehend the reaction to lip syncing.

“People who were around 35-ish or under, who didn’t know the scandal, were like, ‘Why in the world was there such hate for this?’ And they’re blown away,” he says.

Even “older audiences,” Korem hopes, “will look back and be like, ‘that is so insane, the hate that these guys took, and the way people were smashing records.’ It was absurd.”

For the whippersnappers, the uninitiated or those who may have just forgotten, what happened was this: Milli Vanilli exploded in Europe, then America, with anthems like Blame It On The Rain and Girl You Know It’s True. The style and beats were peak 1980s, but there was one problem: Fab and Rob weren’t singing.

Milli Vanilli had been put together by German producer Frank Farian, the group even taking its name from his assistant and sometimes-lover Ingrid; he paired the duo’s style and moves with the vocals of uncredited singers he felt more suited to his songs.

Fans – and some music execs, if they’re to be believed – were caught unawares. Then the recorded vocal track skipped at a Connecticut concert, raising eyebrows; it wasn’t long before the jig was up completely, torpedoed by Farian himself (who did not participate in the new doc) when the performers tried to pressure him into letting them sing for real.

The world felt betrayed, Milli Vanilli gave back their 1990 Grammy for Best New Artist, and the duo’s paths diverged.

French native Morvan, 57, now lives in Amsterdam with his Dutch partner, Tessa, and their four children; Pilatus died in April 1998.

Korem’s new film shines a particularly sad spotlight on Pilatus.

He spent the first four years of his life in a German orphanage after being born to a Black American serviceman and German dancer mother; his adoptive sister, Carmen, agreed to participate in the documentary, offering heartbreaking commentary about her sibling’s desperate longing to be loved.

“She’s the one who picked him out of the litter at the orphanage, so they had a bond,” Morvan says of Carmen. “I’m so happy that she was in there, and she could speak and address all those things that he was going through.”

He says that even when he and Pilatus first met on the party scene in 1980s Germany, he sensed “a void” in his future musical partner.

“He was not held in the beginning,” Morvan says of his friend’s early years in the orphanage. “And I’m not a psychologist, but I know that, if you’re not held at the beginning of your life, this void will take place and pop music, becoming a star and being loved, was a way to just patch it.”

The men became fast friends, bonding over their shared love of style, music and dancing – as well as their pursuit of fame. They began throwing parties and attracting buzz, and eventually Farian – who’d previously engineered another successful Black-fronted European group, Boney M – offered them a contract.

Accounts within the film differ about what happened next. Morvan says a fight erupted when he and Pilatus realized Farian didn’t want them to sing, but they eventually went along with it; Farian’s old collaborator and girlfriend, Ingrid Segieth, claims the duo never had a problem with lip syncing to recorded tracks, so eager were they for fame and fortune.

Regardless of who knew or did what, Milli Vanilli took off, and even Morvan admits that the pair’s egos skyrocketed, too. The documentary outlines their diva behaviour but gets to the heart of Pilatus’ insecurities, as well – how, craving affection, he’d platonically sleep in bed with Segeith, for example.

So deep ran his need for love and acceptance, says Morvan – echoing the words of Pilatus’ sister – that it was all too much for him when it was taken away..

“When that love was disappearing – and it went in full decline, from one day to the next; we didn’t have time to adjust, it just went from hot to cold – that impacted him heavily,” Morvan tells The Independent. “And drugs and alcohol was a way to self medicate … to deal with carrying this chest on our back with a secret locked inside.”

Korem and Morvan say they felt a responsibility to Pilatus as they made the documentary, which includes audio from an interview the late singer gave from a drug rehab clinic in Germany just 60 days before his death.

“That was vital to making the film, because, yes, Fab is the only one who can go on camera and talk, but we … threaded [Pilatus’ audio] throughout the whole film,” Korem tells The Independent.

Between Pilatus’s actual voice and his sister’s interviews, Korem says, “I feel like you do feel Rob’s spirit” in the documentary.

He and Morvan concede that, in some ways, attitudes have changed towards the performance meritocracy. Milli Vanilli imploded “pre-auto-tune, pre reality TV, social media and this plethora of packaged pop stars that we just accept as pure entertainment now,” Korem says.

But when it comes to attitudes about – and concern for – the performers themselves, perhaps not so much progress has been made. In the quarter-century since Pilatus’ death, countless other pop stars have been felled by addiction, suicide and the fickle tide of public opinion.

It’s interesting to note that Milli Vanilli begins streaming on the same day as the release of the new memoir from Britney Spears – a star whose mental health, well-being and treatment by the industry has been examined perhaps more than any other celebrity within living memory.

“The industry is a machine,” Morvan tells The Independent. “And you put human beings in the machine, and they will be treated as components – and if a component in a machine is not making or doing what it’s supposed to do, they’re going to get another component and replace it. That’s not going to change.”

He hopes that, despite that, there are “more steps towards making sure that artists are taken care” given that society, as a whole, is more aware of “the signs of the spiralling down.”

But, Morvan says, “who the artist is surrounded by, it’s the difference.”