Mitch McConnell is the main reason Trump is back

Shortly after Donald Trump won in New Hampshire, Senator John Cornyn announced his support for him. Why does that matter? Because Cornyn is far from a Trumpist. In fact, the square-jawed Republican from Texas negotiated a gun bill alongside Democratic Senator Chris Murphy and then-Democratic Senator Kyrsten Sinema that Trump vehemently opposed. Cornyn’s support today shows that all Republicans — from the furthest right to the most moderate — are now falling into line behind the former president.

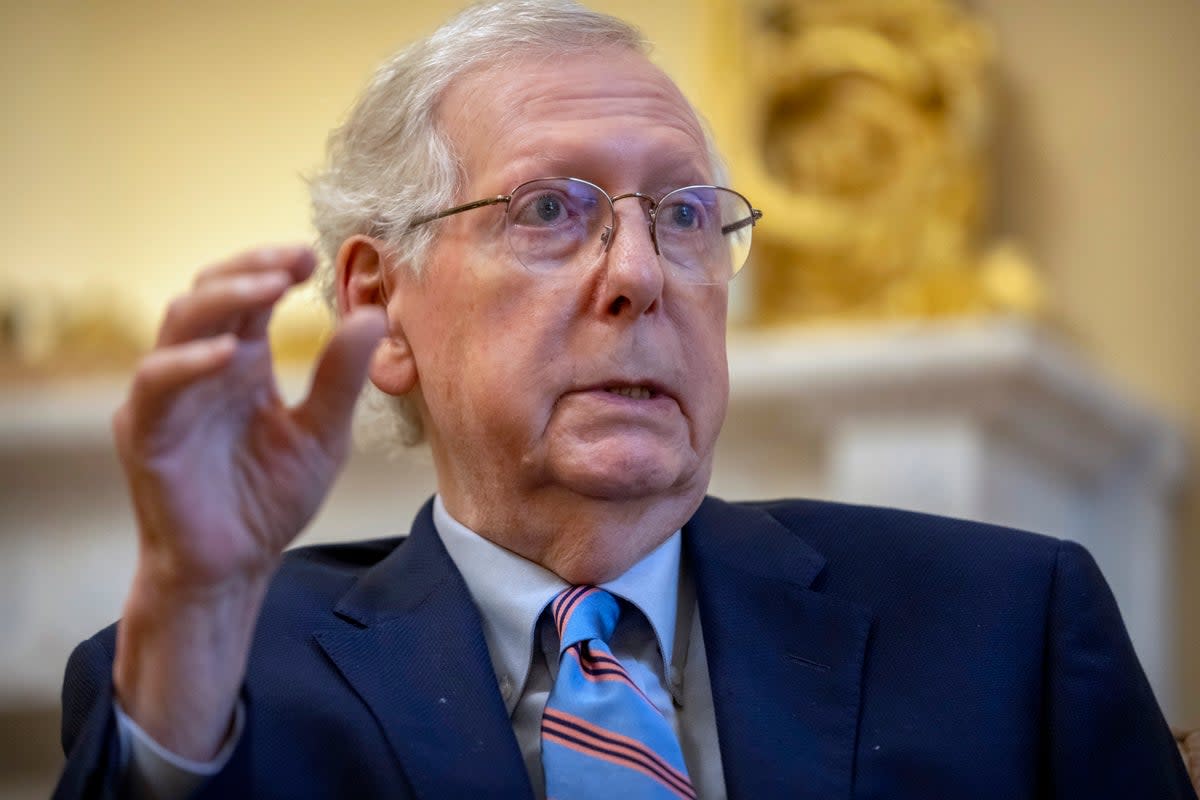

In fact, Trump continues to have Republican leaders get behind him save for one major voice: Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. Trump and McConnell’s relationship is well-documented: the two worked hand-in-glove to confirm a slew of judges, including the three Supreme Court justices who killed Roe v Wade; while they failed to repeal Obamacare, they collaborated to pass massive tax cuts.

Their relationship irrevocably broke after the January 6 insurrection. Elaine Chao, McConnell’s wife, resigned from the Trump administration as Secretary of Transportation after rioters violently attempted to breach her husband’s office.

But as much as the two many not like each other — Trump has taken to calling McConnell “Old Crow” — and as much as the two may not want to admit it, McConnell’s decision not to convict Trump likely facilitated Trump’s return to the top of the Republican Party.

That might surprise some, given that McConnell does not appear to enjoy talking about the former president. He’s not as servile to Trump as former Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, who visited the president at Mar-a-Lago during his impeachment trial. Nor, unlike Speaker Mike Johnson, did he lead legal efforts to overturn the 2020 election results, but rather voted to certify the election.

He also enjoys a far more cordial relationship with President Joe Biden, with whom he served 28 years in the Senate.

But McConnell does remain in thrall to the right wing of his party. Like many Republican elites, he lived in fear of the Tea Party movement of the 2010s that served as the Iliad to MAGA’s Odyssey. He watched Republicans nominate far-right candidates and blow winnable races in 2010 and 2012 — and therefore his chances to become Majority Leader until 2015. Indeed, he was so critical of such candidates that he was considered a “RINO” by his own colleagues for a long time.

It was only when he blocked Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court that McConnell was fully embraced by his GOP colleagues across the spectrum; they realized then that his dislike of the far right was less about ideology and more about the ballot box. Blocking Garland solidified McConnell’s reputation among Republicans and Democrats alike as a cutthroat tactician and enforcer. It also helped Trump ascend to the presidency.

Had McConnell chosen to act on his anger toward Trump after January 6, he likely could have gotten establishment Republicans like Cornyn to take the trust fall with him. We can reasonably presume he’d have been able to get the additional 10 votes needed to stop Trump from running for president again. But that still would have been a minority of Senate Republicans — and he likely would have faced a revolt in the way Liz Cheney did in the House.

In turn, he reasoned that Trump’s words just before the January 6 riot were not legally considered “incitement” and added that “former President Trump is constitutionally not eligible for conviction.”

At the same time, McConnell offered a missive about how to deal with Trump that made his personal feelings clear. “We have a criminal justice system in this country,” he said. “We have civil litigation. And former presidents are not immune from being held accountable by either one.”

McConnell sent out the express hope that district attorneys, the US Department of Justice and the court system would litigate Trump’s actions on January 6. But by handing responsibility off, he made the mistake that almost all of Trump’s opponents make: Assuming he will go away on his own.

Polling has shown that Trump’s support shot up after his first indictment in Manhattan. Similarly, he faced another coalescing effect after his first federal indictment in June.

McConnell likely hoped that by not voting to convict Trump, he could avoid a row among his conference. That, in turn, would turn allow him to focus solely on opposing Biden’s domestic agenda and hammering him during the midterm elections. His short-termist thinking allowed Trump to gather himself and return emboldened.

In recent months, as a man in his 80s, McConnell has sought to build his legacy as a statesman. He has worked with Biden on everything from infrastructure to supporting Ukraine. But none of that will matter if he’s consigned himself to a fate he probably wanted to avoid: Ushering in another Trump presidency due to his own inaction.

Trump in the White House again could mean the full-scale destruction of the Senate Republican conference that McConnell spent decades building. And it will be a legacy he largely facilitated.