As Ottawa promises a better response to natural disasters, communities say they need money now

Ottawa's emergency preparedness minister has warned that this summer could be even worse than last year's record-breaking wildfire season — while communities on the front lines say they need federal money for prevention right now.

"What bothers me is that we take this wait-and-see attitude every single year," said Don McCormick, mayor of Kimberly, a town in the B.C. interior.

"We are in a fire zone. This has been a fire area forever and we'll continue to be. We need to be doing things that are going to allow our forests to manage the fires on their own, and not put our communities in the danger that they are right now."

McCormick's town has spent millions of dollars — much of it money obtained through provincial grants — on measures that helped protect his community last summer. A nearby fire last summer was held off thanks to controlled forest burns conducted years before.

"It is proof of the science around how to provide landscape management is there," he said. "We just need to get the senior levels of government on board, who hold the purse strings."

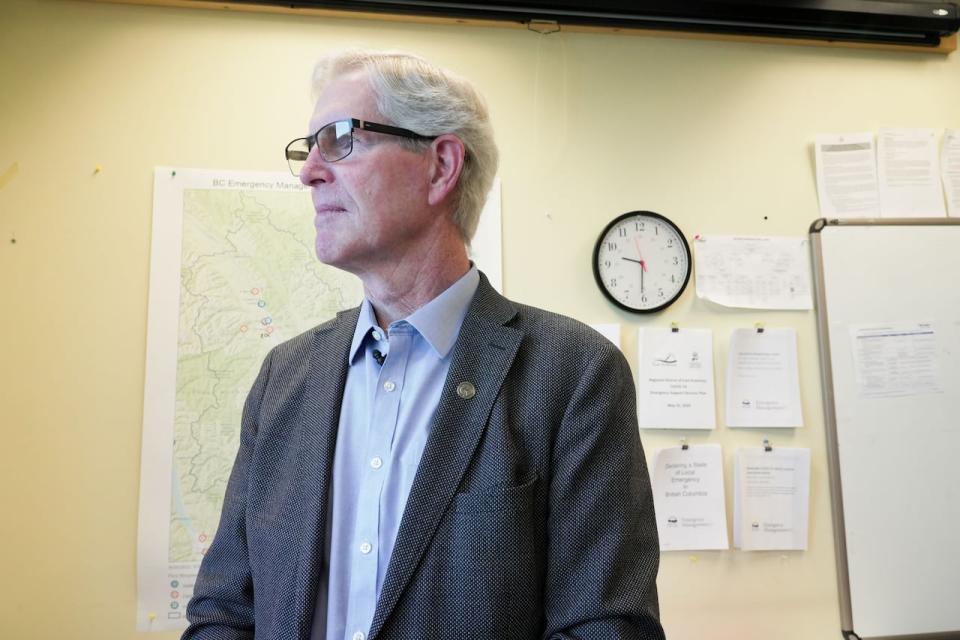

Don McCormick, the mayor of the town of Kimberley in BC's interior, stands inside an emergency operations centre in the nearby community of Cranbrook. (Corey Bullock/CBC)

A massive wildfire last summer forced a three-week mandatory evacuation of Yellowknife. Its mayor, Rebecca Alty, said her city is using its own money to prepare for the coming fire season.

The city has dipped into its own budget to update its communication systems and hire an emergency manager, she said.

Like McCormick, she said she wants more support from higher levels of government before a disaster hits.

"The biggest thing that's missing is dollars to municipalities. When it comes to our territorial funding, we receive no funding to be emergency-prepared," Alty said.

Charred remains on the side of the highway in Enterprise, Northwest Territories on August 20, 2023. (Andrej Ivanov/AFP via Getty Images)

Provincial and territorial ministers met in Ottawa last week with federal Emergency Preparedness Minister Harjit Sajjan.

After two days of discussion, Sajjan told a news conference there are plans to approach this season with a different strategy.

"It's about being co-ordinated to be more responsive," he said.

Pressed by reporters, Sajjan didn't offer details. Instead, he pointed to the need for early wildfire detection. He also spoke about what individuals can do to keep their own homes safe — things like rearranging their patio furniture.

"Actually moving patio furniture out of the way, because most of the patio furniture, when it lights up, it burns longer and it burns brighter and then the house has a potentially to catch on fire," Sajjan said.

No clear plan from Ottawa or provinces: expert

Anabela Bonada of the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation at the University of Waterloo said governments need to act now.

"I was happy to hear about fire smart practices being implemented and being advocated for, but there wasn't a very clear plan on how that's going to go forward," Bonada said.

"We need to hit the ground running. We know what needs to be done. I just keep seeing the issue as implementation."

Minister of Emergency Preparedness Harjit Sajjan hasn't explained how the federal government plans to co-ordinate efforts to prepare for the wildfire season. (Justin Tang/The Canadian Press)

Bonada said Ottawa could act now to create a centralized agency to help manage the response to various natural disasters, since fires, floods and tornados don't respect municipal or provincial borders. It should also push a coordinated effort to recruit and train more firefighters, she said.

"Not much was said on, 'Okay, what is the implementation going to be over the next few weeks?'" she said.

Ottawa also has promised to speed up its post-disaster financial relief. The federal government is in the midst of modernizing its Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements. It has promised to speed up payments and design them to help communities rebuild in ways that makes them more resistant to future natural disasters.

But those changes won't happen for over a year — not until April 2025.

"Boy, do we ever need to hit the speed button," said Craig Stewart of the Insurance Bureau of Canada.

Stewart said the current relief program can't match the scale and frequency of natural disasters the country now sees. It's been around since 1970 but nearly three-quarters of the money paid out through it has been spent in the past decade.

The process for getting money from the program can sometimes take longer than a year, he said.

"If you're a homeowner, you can't be certain of how much money you're going to get, what it's going to pay for, or even how long it's going to take," he said. "It's an unwieldy way to help people recover from disasters."

Alty said her city is still filling out the paperwork to get money from Ottawa to help with last summer's damage.

"We know that it's not a quick process," she said.