Out of the public eye: Group looks at city council transparency

A citizens' group is flagging a transparency problem with municipal councils in New Brunswick.

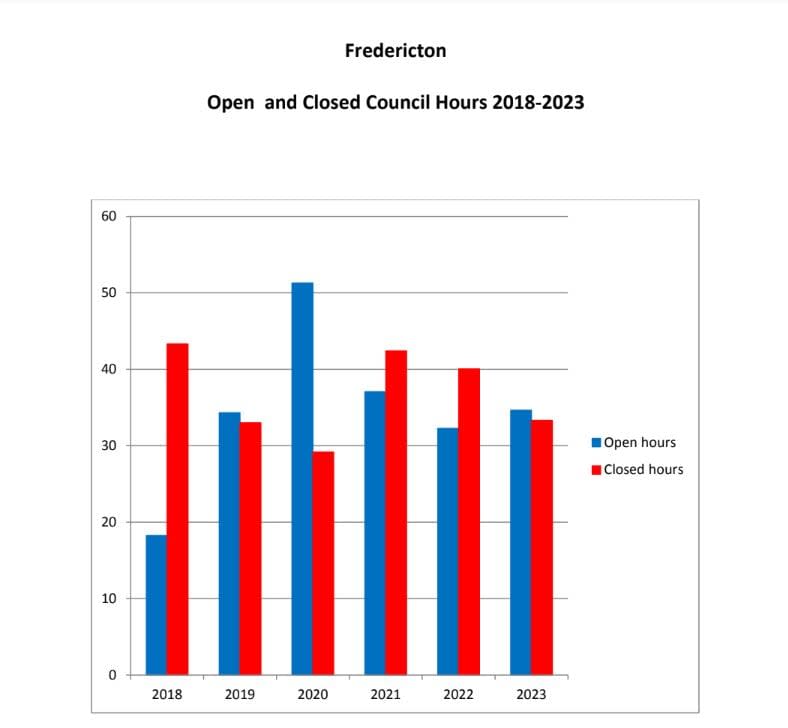

More than half of Fredericton city council meetings are taking place behind closed doors, according to data from a little-known group calling itself Good Governance New Brunswick.

"There's a large period of time where the public and the media … are excluded from what government is doing," said Sandra Bender of Fredericton, identified as a researcher on the project and a founder of the group.

"And that means that we don't know what government is doing."

Lack of transparency makes it difficult to people to hold representatives accountable and to participate in decisions and could make it easier for corruption to creep in, Bender said.

"I wouldn't feel comfortable just sending my money over and saying, 'You go behind those doors and do what you think you need to do and then come back,'" she said.

"There's a high level of frustration and the trust is eroded. And that doesn't work well for either city council or for Frederictonians. So I think transparency is helpful for everybody."

The data is based on official city records of open and closed minutes for council and council-in-committee meetings from 2018 through 2023, provided by the city clerk, said Bender.

It doesn't include committee meetings held on Thursday at noon, noted Fredericton Mayor Kate Rogers.

When those are considered the proportion of council business conducted in open session bumps up to well over two-thirds, she said.

Mayor defends council record on open meetings

Information is made available "at every opportunity" to the extent it is responsible, said Rogers.

"We stay every Monday after sometimes we will have had four or five hours of meetings. I stay afterwards to be in scrum to talk to journalists for anyone that would have any questions. I take calls, I take meetings, I go to schools and share information.

"We are trying to engage the public as much as possible in what we do with our civic governance. … If we can find more ways, we will do that. But we always have to be respectful of what is required to going to closed."

Many of the closed meetings are "council-in-committee" held twice a month prior to regular council meetings, Bender said in a release.

These meetings are meant to deal with operations of the municipality, but it's not clear what topics fall under that umbrella or why the discussions need to be kept from the public so frequently, she said.

Rogers said for some issues, council is required to meet in private.

"They're often personal information, information regarding contracts or relationships with other levels of government," said the mayor."

"It's delicate information that's being discussed and potentially could be jeopardized if we did them in open."

There are good reasons for dealing behind closed doors on occasion, Bender acknowledged — such as when discussing human resources issues, private information about employees, and matters of client-lawyer privilege or having to do with police investigations.

Eight such categories are defined in the Local Governance Act. The act requires that only a general topic and meeting date be recorded for meetings dealing with these matters.

But Bender feels that's too restrictive and said the recording of minutes should be permitted to allow for the possibility additional information may be made public after the fact.

Just because council is allowed to discuss something in private doesn't mean they always should, Bender added.

Open should be the default unless it's going to cause harm, she said.

How Ottawa manages to be more open

Bender cited Ottawa is a good example of a municipality that has put a lot of effort into being transparent.

Less than four per cent of Ottawa council meeting time over the same period was in private sessions.

One way that city keeps in camera meetings to a minimum is by having a group of senior managers and an integrity commissioner review agenda plans ahead of time, said Caitlin Salter-MacDonald, Ottawa's city clerk.

Operational staff are dedicated to making sure the only reports handled in private are those truly required to be, Salter-MacDonald wrote in an email.

When something is done in private, there's either a designated date when the information can later be released or a reason documented about why the clerk and city solicitor think there is a legal reason not to, she said.

Ottawa also makes a lot of information available on its website, Open, Transparent and Accountable Government, including a lobbyist registry, open data, conflict-of-interest registry, memos issued to council, office expenses, executed contracts and reports.

The highest number of hours Ottawa council spent in closed-door meetings for any single year of the study was 12, said Bender.

That compares to a peak of 43 hours a year in Fredericton, she said.

No data from Moncton, Saint John

Documentation was also requested from Moncton and Saint John, said Bender.Saint John didn't respond, and Moncton declined.

Asked by CBC News for an explanation and response, Saint John communications officer Erin White said: "The City is not aware of who this specific request was made to at the City, but we would be happy to provide the information if a formal request is submitted through the City's Clerks office."

Aloma Jardine, Moncton's manager of strategic communications, said staff couldn't find the request and asked for more details about who submitted it and when. Those details were not available at publication time.

Jardine noted Moncton has begun posting the dates and topics of private meetings.

Good Governance New Brunswick was founded in 2020, said Bender. Partly, it grew out of her involvement in the community since 2018, including with provincial and municipal elections.

"This included experiences of women organizing to run more female-identified candidates for council seats."

Bender was recently involved in complaints against Fredericton council over the way the cross-town trail route was decided. That's only tangentially related to the transparency research, she said, and none of the other people who have taken issue with the trail route are involved in the Good Governance group.

Good Governance's goal is to provide information and advocate for good governance, transparency, public consultation and accountability, she said.

Bender said her personal background includes being a retired federal government worker who has worked with non-governmental organizations and non-profits, been a professional educator, volunteered in political campaigns and studied journalism.

She said she is the only member of the group in Fredericton, but a fluctuating number of other people are involved in research projects.

She did not respond to a request for more information about the other members, such as the approximate number, where they are located or their fields of expertise, but Bender described the group as independent and non-partisan.

The group decided not to have a social media presence or website so they could concentrate on research and avoid online toxicity and dysfunction, she said.

Another study related to transparency is partially complete, she said, and results may be shared if the group decides that would be worthwhile.