Race to restore Myanmar's film classics for a second screening

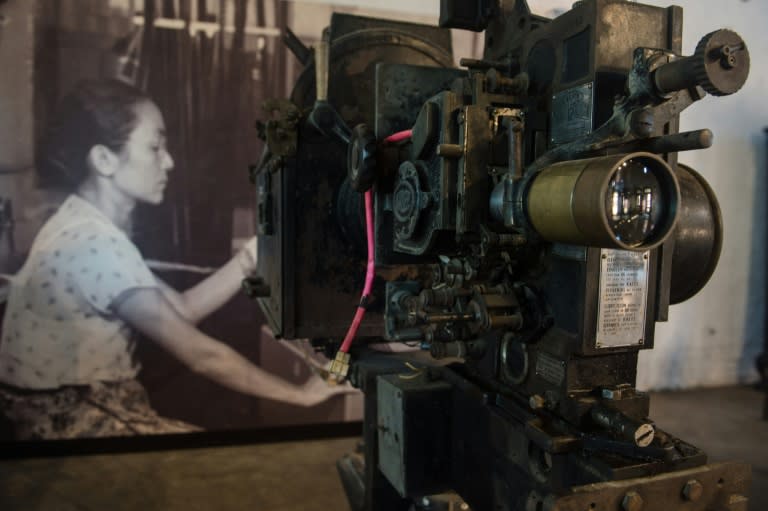

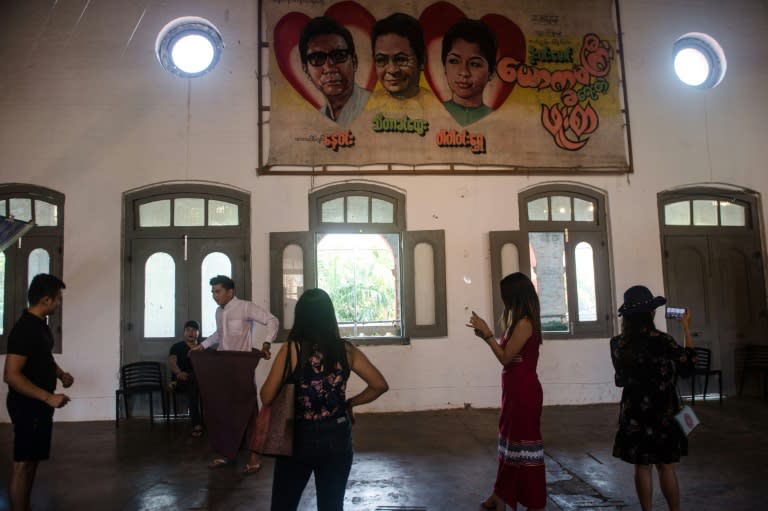

The restoration of a 1934 black-and-white action movie, famed for high-octane stunts including a hot-air balloon escape and a jungle shootout against teakwood thieves, has energised efforts to salvage more of Myanmar's decaying cinematic heritage. The survival of Myanmar's earliest film still in existence, "Mya Ga Naing" (The Emerald Jungle), and its rise to international acclaim is perhaps as unlikely a feat as its lead role's triumph over pythons and bandits with his bare hands. The Southeast Asian country's once flourishing film scene hit a major setback with the arrival of a military junta in 1962 that enforced stringent censorship and gutted the economy during a 50-year reign. As the creative climate withered, Myanmar's merciless heat, torrential rains and stifling humidity took its toll on delicate film reels in a country that had neither the resources nor know-how to store them properly. Some reels were recycled to save money and now only a dozen of the country's early black-and-white pictures remain. "Mya Ga Naing", originally a silent movie that later had music and printed title cards added, is the oldest to have been found so far. It languished in the state archives for decades before specialists in Italy spent one year painstakingly retouching the film frame-by-frame, screening the restored version in 2016. Experts spent hundreds of hours at the laboratory of L'Immagine Ritrovata (The Rediscovered Image) in Bologna removing every small scratch and spot from the film and digitising using various resources including some film found in archives in Berlin -- a testament to how far the original movie travelled. "Each time the restoration progressed, it was like a new birth for the film," said Severine Wemaere, co-founder of MEMORY! Cinema, which oversaw the restoration and raised funds from donors for the $100,000 price tag. "It was very moving because we could tell that we were in a country of cinema." - Sound or colour? - The classic has also played at festivals in Singapore, Thailand and Switzerland as well as enjoying regular screenings at home in Myanmar. A live group of musicians accompanied a recent sold-out performance in Yangon, staying true to an original soundtrack added in 1954 that mixes local traditional music with western jazz. The film gained further international acclaim this year after UNESCO awarded the film a place on its Asia-Pacific list of "documentary heritage of influence" -- a nod not just to the movie, but also to Myanmar's cinematic tradition. The country's first-ever film was screened in 1920. By the 50s, the industry was in its heyday with Myanmar filmmakers pumping out scores of features each year. But the plot turned in the latter half of the 20th century as military rulers crushed creativity and closed the country off to foreign influences and technology. While nearly all the earliest movies have been lost, the successful revival of "Mya Ga Naing" is spurring a movement to preserve what remains. The next film to be restored in 2017 was Pyo Chit Lin (My Darling), a 1950 comedy shot on such a tight budget that director Tin Myint had to choose between sound or colour. He opted for the latter -- making it the country's earliest known surviving colour film. - Every second counts - Contemporary Myanmar filmmaker Maung Okkar is playing a lead role in the effort to salvage his country's classics. Few could be better placed -- the 31-year-old has moviemaking in his blood with both his father and grandfather renowned directors. In 2012, Maung Okkar realised with horror that some of his family's original reels were damaged beyond repair while others were slowly decaying in his storeroom. "Some films could not be restored and, for me, it was as if I had lost one of my parents," he remembered. "I learned there were other old films which were not looked after properly and decided to do it myself." After receiving training in restoration and archiving techniques in Italy, he launched "Save Myanmar Film" in 2017 with a group of fellow filmmakers. Their slogan is "Every Second Counts!" and they aim to find and preserve as many old reels and other cinematic paraphernalia -- including cameras, projectors and film posters -- as possible. Some two thousand people viewed an exhibition and screenings held by the group this May in Yangon's prestigious former parliamentary building, and plans are under way to restore a third film. The clock is ticking, with all of the surviving films still piled up in metal tins in Yangon's crumbling state archive building. Round-the-clock air conditioning is an improvement from the past but the temperature, at 16 degrees Celsius (61 degrees Fahrenheit), is still far above the optimal level of four degrees Celsius. Actress Grace Swe Zin Htaik, 65, starred in many of Myanmar's biggest films in the 70s and 80s and faces the challenge of organising the upcoming 100th anniversary of the country's movie industry. "People in this country have no idea how to value the old movies," she said wistfully while tracing her finger along the ramshackle shelves that are home to the remnants of the country’s cinematic heritage. "(Through) old movies we can see our history, we can see our culture, we can see our identity and values."