Remembering the Artist June Leaf in Her Own Words

With Monday’s passing of June Leaf, the art world has lost a deep-seated original, whose life, like her body of work, extended beyond any trace of constraints.

Plans for a tribute were not immediately known Tuesday.

More from WWD

Eva Jospin Brings Dior-commissioned Embroidery Work to Versailles Palace

Design Shanghai's New Collectible Art Fair to Bow in October

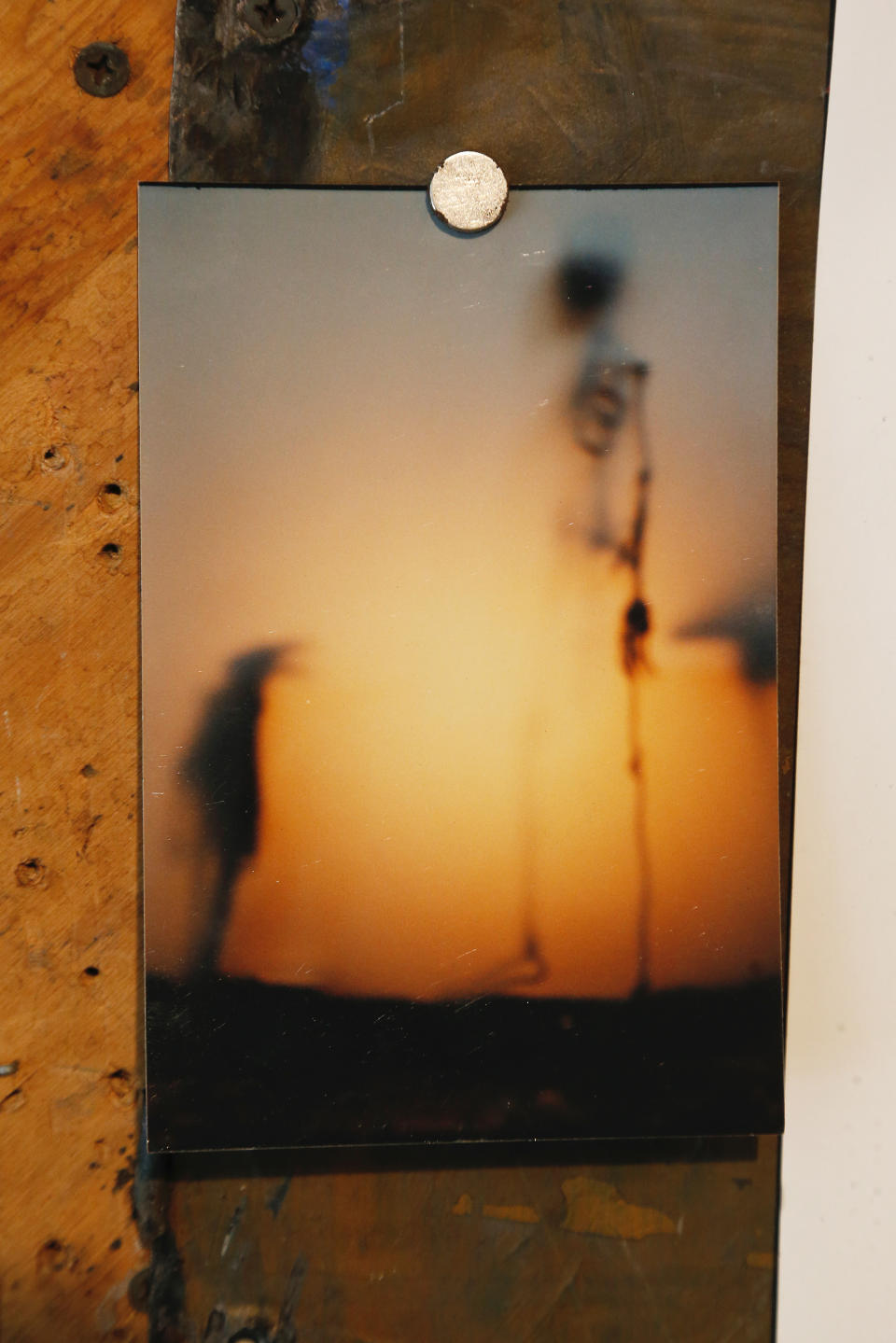

Born in Chicago in 1929, Leaf cut short her studies at the Art Institute of Chicago. Certain of her calling, she was up-and-out of the Bauhaus School after only three months, moving to Paris for a stretch of self-study, and gleaning skills from Paul Klee, Mark Tobey and other talents. She met the futurist Buckminster Fuller in her school days, took to graffiti in the 1940s and kept the forward-reaching ethos. Leaf started drawing robotics in the ’70s, including the 1975 watercolor “Computer Woman in Landscape.” When Frank was working on a film about the Rolling Stones’ 1972 American tour, “Cocksucker Blues,” she gave him a small Polaroid camera and he started writing on the photographs as she was known to do.

In an interview with WWD in 2016, Leaf attributed her steely work ethic to her mother — the family breadwinner who wasn’t above hauling cases in her father-in-law’s tavern and liquor store.

At that time, Leaf repeatedly sprang up from a wobbly wooden chair to dig up a painting, photo or widget to better illustrate her points and even lugged an antique Singer sewing machine across the room. The artist mentioned how her physical therapist thought she moved like someone who grew up on a farm. (She didn’t, but you could see why someone might think she had.) Grasping how the body moves was something Leaf took to, studying ballet as a child. Movement and flight then became recurring themes in her work, with Leaf always drawing her figures in space to ensure they could move. “So when I draw I am dancing,” Leaf explained in 2016.

Leaf’s creations are held in such museums as the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Upon the unveiling of “June Leaf: Thought Is Infinite,” Leaf left the selection to curator Carter Foster. “Many people said, ‘God, that was courageous of you not to be part of the choosing of the work.’” Leaf once said, “Then courage is part of being an artist. Isn’t it about taking chances? Where would we be if we didn’t take chances? We wouldn’t be who we are.”

Her marriage to the seminal photographer Robert Frank, who predeceased her in 2019, opened up a 44-year artistic union and a moniker. Leaf told WWD in 2016, “I thought today I should talk about it. I should announce it. I should not run away and say, ‘Oh, she’s married to Robert Frank. Yes, she’s married to Robert Frank and she’s still going.’”

Here are excerpts from Leaf’s interview about her career, marriage and ambition.

Critiquing Her Creations

J.L.: “There’s a lot that goes into my drawings and that’s what I saw. I thought, ‘Well, if all else fails this is a person who is looking for something, and it takes her a long time to get there but she gets there.’ There’s nothing decorative about it. It’s a search. You can see that I’m searching. I realize that I don’t see that often in paintings. You see it in writing. Or maybe sometimes in the choreograph in a dance where the dancers are portraying some evolution of their souls. I thought if all else fails this person is searching.”

Relinquishing Curatorial Control

J.L.: “Doesn’t that sound kind of special in the art world, which is so full of concern of what people think of you and whether you made an important painting or what moved you? I just liked that this person was touched, I left him alone, and I just kept working.”

Smartphones Sparked Renewed Appreciation of Frank’s Photography

J.L.: “When we sit outside, people walk by and practically get on their knees. And I understand. I think I understand better than anyone. We are at these crossroads in time. It’s like when they invented the printing press. All of a sudden people could read books and they didn’t have to listen to what the priests said. Everything was accessible to people. Well, photography is the same revolution. All of a sudden everybody is empowered, and they need it, in the way they needed books. And Robert is the one that elevated that creative process to the level of art.”

Living With a Marquee Talent

J.L.: “I’m up to it. I guess that’s what I want to say. He doesn’t make it less for me. He puts it right under my nose — the kind of challenge a painter is facing everyday. It’s right there. And I feel really good. I’m strong enough to be empowered by it but not threatened by that. I feel that’s fate.”

Meeting Frank Through First Wife Mary (an artist who’d asked Leaf for help finding a new gallery) at a Housewarming Event for Their Daughter Andrea

J.L.: “I looked at him and I thought, ‘Oh, there he is. He’s more raggedy than I thought he would be; he’s more arrogant than I thought he would be. He’s married, and I am so happy that he’s married because that is a very difficult man.’ That’s exactly what I thought. I just walked away from him. He tried to talk to me. I just didn’t like the way he approached me as a woman. This is kind of private. It’s nice, it’s true and it’s life.”

Life in the One-pub Town of Moab in Cape Breton

J.L.: “When I met Robert, it was like we started a new life, and we left New York. I felt like I was finally with the love of my life. I don’t know how advanced he was along those lines, but I had enough for both of us. Art was behind me. It was like, ‘Now maybe from this you make art.’ This is the right person. It’s not from art that you make art.”

Discussing Work With Frank

J.L.: “Never. It’s like, it’s not important.” The blue jays building a nest in the ailanthus tree of heaven outside of their Bleecker Street apartment, (a four-floor former flophouse they bought for $40,000,) was more their speed or the “who’s healthy, who’s not” game that inevitably comes with age.

Assessing an Early Collage From 1949

J.L.: “I was only 18 years old. It’s the Chicago Tribune and I see it as a castle.”

“A Very Good Painting” of Allen Ginsberg in the Buff

J.L.: “He wanted me to and I wanted to.”

The Legal Dispute Around the Unreleased Frank-shot Rolling Stones Documentary

J.L.: “I guess they didn’t like that drugs were shown.”

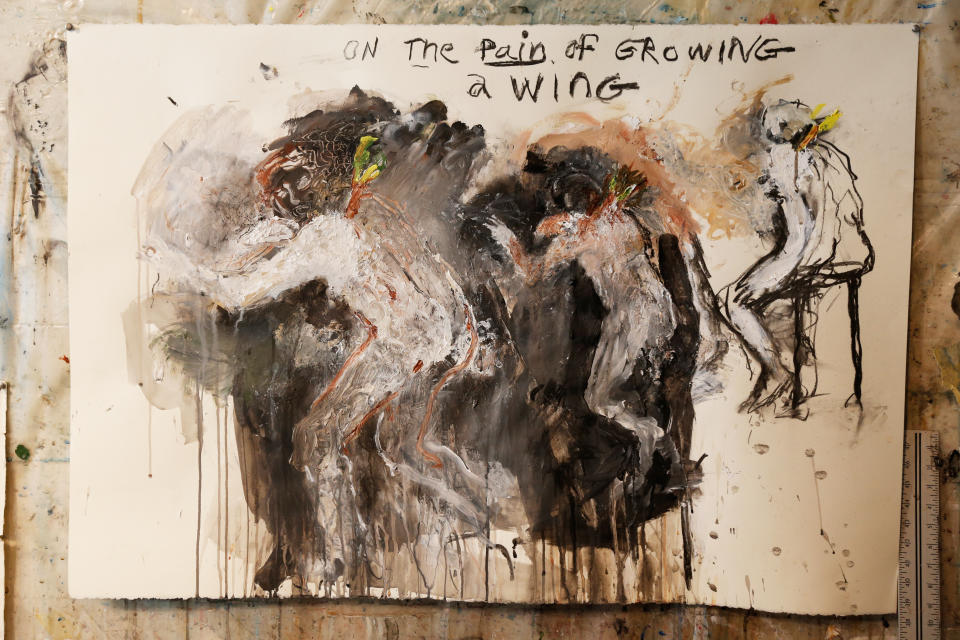

Her Own Standing in the Art World

J.L.: “Maybe I don’t want public acclaim. I want to survive with that integrity that is so precious to me. The fact that I could make that drawing [gesturing toward an easel with ‘On the Pain of Growing a Wing’] made me think ‘Oh good, you’re still a scientist who can invent something that goes with your life. I guess I just want to live right. Living right is very important — loving right. It’s not that I’m such a great humanitarian or lover, but in my world, there is a right way to live with someone. That’s all.”

Best of WWD