Republicans are desperate for attention — and it's decimating their ability to govern

If only they cared.

In the end, the only man who could unify House Republicans behind him was a relatively little-known and mild-mannered evangelical Christian from Louisiana.

But the 22 days that led up to Rep. Mike Johnson's election as speaker were anything but calm, bringing fresh convulsions and drama with each passing day as the cantankerous GOP conference forced three successive nominees to withdraw their candidacies.

With a speaker now safely in place, the House is quickly getting back to its old ways: taking up resolutions to censure and potentially even expel its members as soon as next Wednesday.

As the speaker saga wore on, it provoked questions among some House Republicans: How could it be that they had failed to elect a speaker for so long? Why wasn't winning the party's nomination enough to claim the gavel? And why did it feel like there were no consequences for stepping out of line in the first place?

Many of them laid the blame squarely on Rep. Matt Gaetz. When the Florida congressman took what felt like an unimaginable step — triggering a successful vote to boot Kevin McCarthy from the speakership — it typified the kind of attention-hungry bomb-throwing that has become routine in certain corners of Congress.

"It's disgusting," an infuriated Rep. Garrett Graves of Louisiana declared in a floor speech, brandishing a fundraising appeal from the Florida congressman on his phone.

—The Recount (@therecount) October 3, 2023

While Gaetz maintains otherwise, his angry GOP colleagues have plenty of evidence to make their case that it was an attention ploy. The Florida congressman records a podcast called "Firebrand" on a near-weekly basis, occasionally guest-hosts right-wing news shows, and shamelessly fundraises off of his hardline tactics in Congress.

The chaos that parked itself in the Speaker's chair was, for the nihilists among us, entertaining. But it also underscored an unavoidable conclusion: lawmakers have come to relish their roles as carnival barkers, building their schedules around cable news TV hits while integrating theatrics and fundraising pitches into what's supposed to be the mundane work of legislating.

"You see it every day here, right?" Sen. Thom Tillis told me. "You see it in the made-for-TV comments in committee meetings that have, oftentimes, little or nothing to do with the subject matter of the meeting."

The North Carolina Republican played a major role in last year's effort to primary Rep. Madison Cawthorn, who infamously told colleagues that he "built my staff around comms rather than legislation." Tillis fretted that attention-grabbing has "become part of a business model for people here."

Republicans in particular seem to increasingly prefer the influence that comes through online virality and media coverage over the institutional power that can take years of hard work to accrue. And it's corroding the party's ability to govern.

As crises erupted or continued overseas, and the mid-November deadline for averting a government shutdown drew ever closer, the party busied itself with defenestrating speaker nominee after speaker nominee.

"The 24-hour news cycle," Rep. Greg Murphy of North Carolina lamented on Twitter, "has destroyed Congress."

'A worthy topic of consideration'

"I'm wearing the scarlet letter," Rep. Nancy Mace recently declared after exiting a GOP conference meeting, eagerly turning toward the assembled reporters with a wide smile on her face. The bright red "A," she explained, represented her plight: "Being a woman up here, and being demonized for my vote and for my voice."

One week earlier, the South Carolina congresswoman voted to oust McCarthy, and she had received more ridicule than the other seven Republicans who did the same thing. But during her nearly three years in Congress, Mace has mastered the art of generating media coverage for herself, most often by telling reporters outside the House chamber that her party's latest major legislative initiative was too extreme, only to walk inside and vote with the party anyway. The giant red "A" emblazoned across her shirt was simply the latest stunt.

To hear her tell it, however, she never meant to make such a splash.

"I'm actually surprised it got the amount of attention it did," she told me as we walked down a basement hallway beneath the Capitol. It was a firetruck red "A," I told her. Of course it was going to draw attention.

"I know, but not — it got way more than it should have," she said. Then she was gone, rounding the corner towards the latest House Republican conference meeting, where a throng of reporters and cameras awaited.

It's part of the playbook: Deny you are doing what you are very clearly, in fact, doing. And Mace isn't the only lawmaker guilty of it.

"That sounds like a worthy topic of consideration," Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri — a frequent presence on Fox News who parlayed his infamous January 6 election objection into a gangbuster fundraising quarter — told me when I asked him how he thought about his party's relationship with the media. "I can't say I've given it much."

For decades, a celebrity industrial complex has slowly developed around the GOP. Ronald Reagan, after all, was a Hollywood actor before he became the governor of California. Though it has become somewhat trite to talk about Donald Trump's presidency as the culmination of that model of politics, the simple fact is that he demonstrated its success — at least electorally.

The revolving door — the method by which lawmakers use their political platforms to set themselves up for success after they leave office — isn't new. (Hello, Nicole Wallace and a large chunk of the Obama administration.)

But for Republicans, there's much to be gained from having one's name in the headlines, including invitations to conservative conferences where you're treated like a rock star, the chance to write books that make you a fat chunk of change, and the possibility that whenever you get bored with the hard work of governing, there may be an empty seat prepared for you in conservative media.

In other words, it provides an alternative set of benefits that encourage a retreat into the echo chamber rather than attempts to actually do the work.

'Is it good for governance? I don't know'

There's also a more immediate reason to pursue this route: raising money.

For years, the Republican Party has relied on what Sen. JD Vance of Ohio called the "traditional, old-guard fundraising base" — wealthy industry titans, corporate PACs, and other business-aligned entities. It's a system that does not require its participants to possess a massive celebrity platform, but rather a willingness to quietly advance the interests of whoever's footing the bill.

But as the party continues in its populist, Trumpian direction, those relationships have begun to fray, and Republicans are increasingly doing what Democrats have long successfully done: seeking out more modest contributions from a broader swath of ideologically driven donors.

"What's actually going on is that we live in a new media ecosystem," Vance told me. "That media ecosystem influences a very new and different fundraising environment that's more built around small-dollar donors than large-dollar donors, so there's a lot of political disruption."

Vance is saying the quiet part out loud: the theatrics and stunts that characterize much of the activity taking place within the Capitol are about fundraising.

There's evidence to suggest that the small-dollar donor economy is driving radicalization on the right. One recent study even found a negative correlation between corporate PAC contributions and election denialism — the more corporate cash they got, the less likely they were to object to the 2020 election results on January 6.

What someone like Mace is doing, then, is clumsily trying to adopt the fundraising model that made Reps. Jim Jordan and Marjorie Taylor Greene the biggest Republican fundraisers outside of party leadership during the 2022 cycle.

"You're damn right I'm fundraising off of this," Mace told Fox News during a television hit from inside the Cannon House Office Building, "because the establishment is coming after me for taking a principled stand." (The South Carolina congresswoman went on to violate House ethics rules by asking viewers to contribute to her campaign.)

"Is it good for governance? I don't know," Vance said of the new viral fundraising paradigm. "I think it's inevitable, so we have to figure out how to make it good for governance."

'Attention is not an end'

Republicans have a monopoly on neither splashy fundraising nor the pull of celebrity. Democratic senators infamously fundraised off of the 2018 confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and former Biden administration officials like Jen Psaki and Symone Sanders secured shows on MSNBC before the president's first term was even over.

The attention economy doesn't preclude an ability to govern — an effective politician might seek to harness their celebrity towards worthy ends. But it's been far more disruptive for Republicans than Democrats.

"Attention is not an end, it's a means," Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York told me. "I think what they struggle with is understanding what their ends are."

Even a single tweet from Ocasio-Cortez has the potential to generate headlines, yet she has remained a team player for Democrats, to the chagrin of some on the left. Generally speaking, the congresswoman tries to be intentional about how she wields that influence.

"Everything about this place is about choosing when you're going to fight and choosing when you're going to conserve," she told me. "For that to happen, you need to have things that really matter to you."

Republicans would, perhaps rightly, protest that they do have things that matter to them, and things that they hope to change about the country. At the same time, the only major policy change that the party was able to muster during its most recent shot at unified government was a modest set of changes to the tax code.

Perhaps it's simply a matter of identity: Republicans are dispositionally less interested in the proper functioning of the government.

Ahead of last month's potential government shutdown, Rep. Bob Good of Virginia said at a press conference that "most of what we do up here is bad anyway" and that most people "won't even miss it if the government is shut down temporarily."

And speaking recently in a Twitter Space, Gaetz said that the protracted nature of the quest to find a new speaker — which had stalled any movement of legislation through the House — had a "silver lining" in that it prevented more Ukraine aid from getting approved.

'How to be more relevant'

As I made my way around the Hill, chasing after lawmakers to ask them whether members of their party had become too camera-hungry, it often felt like there was a breaking-the-fourth-wall dynamic at play. Many Republican lawmakers immediately flipped my questions back toward me, arguing that the media itself is the problem.

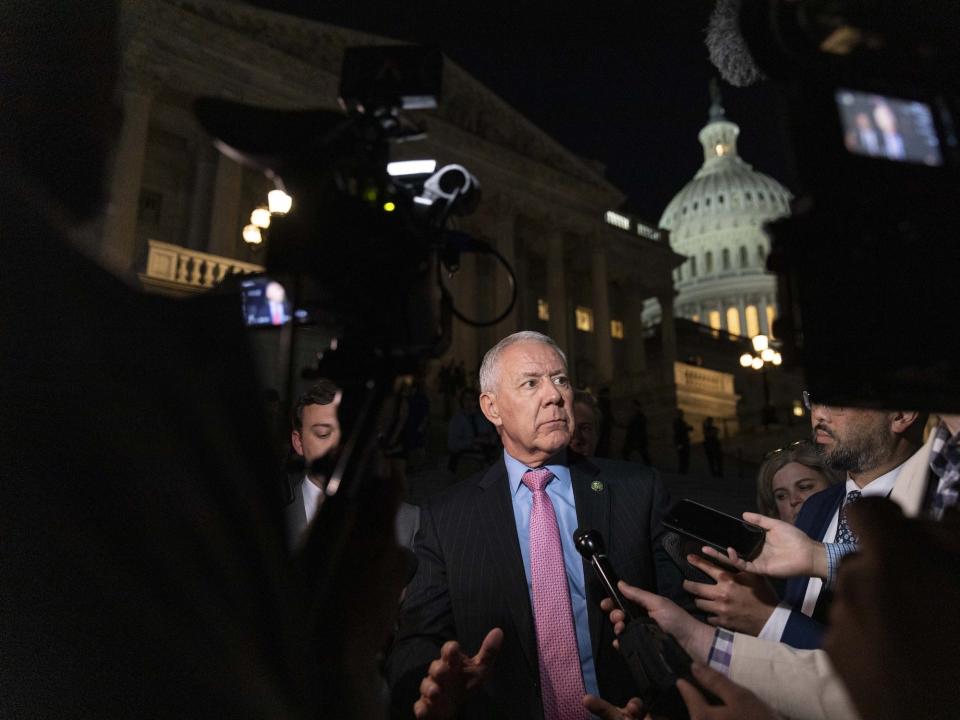

"I guess I shouldn't be talking to you, then," Rep. Ken Buck of Colorado quipped, while Hawley deadpanned that "you guys are generally a very negative influence."

"If you guys continue to give airtime and platform to folks like that, don't be shocked then that that's what people do," Rep. Mike Lawler of New York said.

Yet Republicans have agency in all of this, and what has happened over time is not simply a story of well-meaning people responding to perverse incentives, but of Republicans seeing those incentives and consciously deciding to take advantage of them.

"They're doing it for the purposes of exposure and money," Tillis said. "If there is a long-term goal in mind, boy, I'd like them to reveal it at some point, because I've been here for eight and a half years, and I've seen people like them come and go."

Some have adapted to the terrain better than others. Take Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas, for example — a failed presidential candidate who created an entire media ecosystem and brand around himself, the crown jewel of which is a thrice-weekly podcast called "Verdict" that Cruz once told me is a "critical part of the job."

"I think we have a responsibility to engage in the arena of ideas," said Cruz. "That being said, simply being in the media for publicity's sake is not a worthwhile goal." (Unfortunately, Cruz didn't name names.)

Buck, one of the eight Republicans who voted to oust McCarthy, raised eyebrows last month after the New York Post reported that he was eyeing a gig as a CNN contributor. The Colorado congressman had become an outspoken opponent of the impeachment inquiry into President Joe Biden, and ditching Capitol Hill for cable news seemed to fit with the narrative that he's becoming the next Liz Cheney.

Buck denied the framing of that story, telling me that he simply wanted to know how to get booked on TV "if I've got an important point I want to make."

"I talked to executives, producers, others about how to get on TV more, and how to be more relevant," he said. "And then I also said, at some point, I'm gonna be leaving Congress. And you know, what does that look like?"

Read the original article on Business Insider