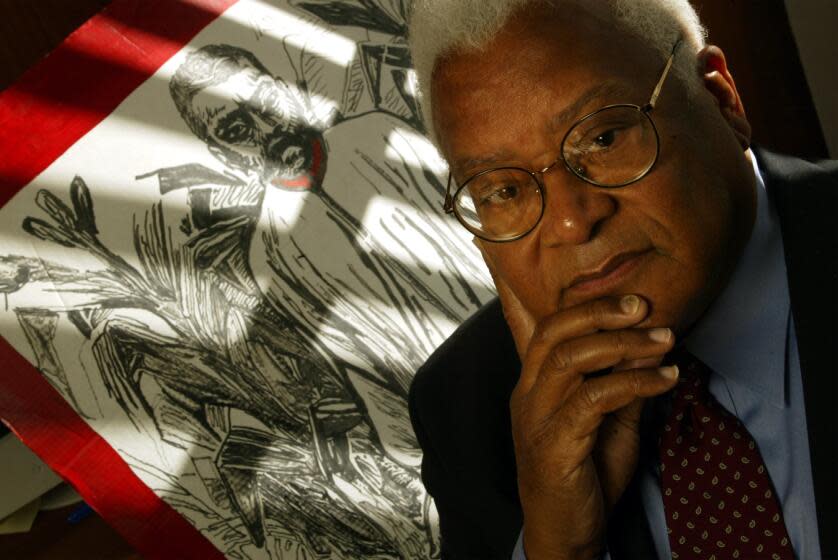

Rev. James Lawson, civil rights leader who led Nashville lunch counter sit-ins and Freedom Rides, dies at 95

James M. Lawson Jr., a Methodist minister who became the teacher of the civil rights movement, training hundreds of youthful protesters in nonviolent tactics that made the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins a model for fighting racial inequality in the 1960s, has died. He was 95.

Lawson, who for decades worked as a pastor, labor movement organizer and university professor, died Sunday of cardiac arrest en route to a Los Angeles hospital, his son J. Morris Lawson III told the Washington Post.

Recruited by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Lawson organized and led weekly workshops on nonviolent action in Nashville and other hot spots of the movement. The workshops trained many future leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, including Rep. John Lewis.

“I truly felt … that he was God-sent,” Lewis once wrote of Lawson. “There was something of a mystic about him, something holy, so gathered, about his manner…. The man was a born teacher, in the truest sense of the word.”

Called “the leading nonviolence theorist” by King, Lawson had studied Gandhi’s philosophy in India before joining the struggle in the South. He led seminars throughout the region and became a roving troubleshooter for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

In 1968, he invited King to speak to striking sanitation workers in Memphis, where the charismatic preacher, who had anticipated his own death, was assassinated.

Lawson worked with various civil rights groups in the South until 1974, when he moved to L.A. to become pastor of Holman United Methodist Church. He led the church for 25 years. He retired in 1999 but remained an activist for peace and social justice.

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, in a statement Monday, said, “Reverend James Lawson Jr.'s life and legacy reverberates in the continuing movement to advance social and economic justice in Los Angeles and beyond. He dedicated his life to equality and justice and helped train a generation of national leaders. ... These teachings changed the course of history.

“Here in Los Angeles, Reverend Lawson taught many activists and organizers and helped shape the civil rights and labor movement locally just as he did nationally. ... Reverend Lawson was also an invaluable mentor to me — I continued seeking his counsel throughout my time as an organizer, an activist and as an elected official. He was there for me as I know he was there for countless civic and faith leaders here in Los Angeles who were guided and influenced by his teachings."

James M. Lawson Jr., the son of a proud Black preacher, did not always practice nonviolence. As a young boy in Ohio in the 1930s, he smacked a white child for shouting a racial slur at him.

Luckily for Lawson, there were no repercussions — until he got home.

“Jimmy,” his mother said when he told her what he had done, “what good did that do? There must be a better way.”

Busy in the kitchen, she did not look at him when she delivered her reprimand, but her words resonated. Lawson felt his world “just sort of stopped,” he later recalled. “And somewhere way in the deep of me I heard myself saying, ‘I will find that better way.’”

His search led him to India, where he studied Mohandas K. Gandhi’s ideas about nonviolent resistance. After returning to the United States, he applied what he had learned to the civil rights movement, blending Gandhi’s principles with biblical insights to forge his philosophy of nonviolence.

Lawson was a pivotal figure in some of the most important campaigns of the movement, including the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins, the first Freedom Ride and the social justice battles he led as pastor of Holman United Methodist Church in L.A.

The Montgomery bus boycott King launched in 1955 had proved the potency of nonviolent protest. But it was Lawson who brought disciplined instruction to the youthful protesters who would take the civil rights movement to the next stage. He taught them not only the lofty principles of passive resistance but also fundamental tactics, including how to withstand taunts and physical attacks, avoid breaking loitering laws, “even how to dress” for a sit-in, historian Taylor Branch wrote, which meant “stockings and heels for the women, coats and ties for the fellows.”

His nonviolence workshops nurtured many of the leaders who would propel the movement in the 1960s, including Lewis, who was one of the organizers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, known as SNCC.

“I couldn’t have found a better teacher than Jim Lawson,” Lewis wrote in his 1999 memoir. “It is not hard to find forgiveness. And this, Jim Lawson taught us, is at the essence of the nonviolent way of life.”

Read more: John Lewis, civil rights icon and longtime congressman, dies

Born Sept. 22, 1928, in Uniontown, Pa., Lawson grew up in Massillon, Ohio, the son of a Jamaican-born seamstress and an itinerant Methodist minister who packed a gun when he traveled in the South. His father “believed that I should fight to defend myself,” Lawson, the sixth of nine children, recalled in a 2000 interview with National Public Radio.

He was in high school in the 1940s when he staged his first sit-in, targeting a Massillon restaurant that refused to serve Black people. The owner served him but told him never to come back.

After high school, he attended Baldwin-Wallace College, a Methodist college in Berea, Ohio, and joined the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation. When he was called to military duty during the Korean War, he refused the draft and was sent to prison for 14 months.

In 1953, Lawson joined a Methodist mission to India and devoted himself to studying Gandhian nonviolence. He was still in India in late 1955 when he read a newspaper story about the Montgomery bus boycott. “I saw that as an answer to a prayer,” Lawson, in a 1984 Times interview, said of the protest that was led by King. “My reaction was to start shouting for joy.”

He returned to the U.S. in 1956 and enrolled in the Graduate School of Theology at Oberlin College, where he met King in 1957. King, who had come to Oberlin to speak, urged Lawson to join the movement.

In 1958, Lawson moved to Nashville and enrolled in Vanderbilt University’s divinity program. He also joined the Nashville Christian Leadership Council and began holding workshops on nonviolence.

Lawson relied heavily on role-playing, and often asked students to taunt others with racial insults to help them learn self-restraint. He showed the students how to run an orderly sit-in by filling lunch counter seats in shifts. He also showed them ways to minimize injuries by maintaining eye contact with their assailants and using their bodies to help distribute the blows that were sure to come.

In November 1959, Lawson’s students staged three practice sit-ins. “We just did it quietly,” without press coverage, he told The Times in 2014. “We called them part of our discovery process.”

He cut short the training period after students in Greensboro, N.C., received national media attention with a series of impromptu sit-ins that began on Feb. 1, 1960. A few weeks later, the Nashville students — a “nonviolent army” about 500 strong, drawn from Fisk University and other local colleges — leaped into action, occupying three downtown Nashville lunch counters. Over the next three months, more establishments were targeted, including bus terminals and major department stores.

“It was clear we had a very disciplined movement … with students as our primary energy,” Lawson said.

When 81 students were attacked by a group of whites and subsequently arrested, Lawson was expelled from Vanderbilt. Faculty members resigned in protest, generating headlines across the country.

The turning point came when the home of an attorney for the jailed protesters was bombed, triggering a mass march to Nashville City Hall and a boycott of white-owned businesses. In May 1960, three weeks after the mayor appealed to white citizens to end discrimination, Nashville lunch counters began to serve Black people and sit-in campaigns soon spread to dozens of other Southern cities.

Lawson believed that sit-ins were more effective than lawsuits, which he criticized in a 1960 speech at Shaw University in North Carolina as “middle-class conventional, halfway efforts” to deal with grave social injustice.

Longtime activist Julian Bond recalled in “Voices of Freedom,” an oral history of the movement, that Lawson sounded “like the bad younger brother pushing King to do more, to be more militant” and had “a much more ambitious idea of what nonviolence could do.”

The day following Lawson’s speech, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was founded with a statement of purpose drafted by Lawson. Initially led by Marion Barry, the future mayor of Washington, SNCC helped drive major civil rights campaigns, including voter registration projects and the 1961 Freedom Rides.

When the first Freedom Ride was derailed by mob violence, a small group of Nashville students trained by Lawson completed the dangerous bus trip from Montgomery, Ala., to Jackson, Miss. Lawson accompanied them and was arrested along with other Freedom Riders in Mississippi after some of the protesters entered the whites-only restrooms at the Jackson terminal. At Lawson’s urging, they refused bail, which impelled hundreds of other students to join the crusade against segregated interstate travel.

In 1962, Lawson became pastor of Centenary United Methodist Church in Memphis. He left for L.A. in 1974 when he was hired to lead Holman United Methodist Church.

Over the next 25 years, until his retirement in 1999, he remained a prominent activist. He was co-chair of the Gathering, a group of 200 South Los Angeles clergymen who protested the Los Angeles police shooting of Eula Love in 1979, and headed the Los Angeles chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He was arrested several times at protests, including a rally against U.S. military aid to El Salvador in the late 1980s. In 2000 he risked a church trial for blessing a lesbian wedding.

After Lewis died in 2020, Lawson, at the age of 91, paid tribute to the congressman alongside three former U.S. presidents at a memorial service at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. In an eloquent eulogy bookended by the poetry of Czeslaw Milosz and Langston Hughes, he exhorted Americans to “practice the politics of the preamble to the Constitution” as the “only way” to honor Lewis’ life.

He said he had no regrets about the fateful invitation he extended to King to address striking sanitation workers in Memphis in 1968. King was assassinated there a day after giving his famous “Mountaintop" speech, in which he spoke of his dream of equality and added, “I may not get there with you.”

“Martin expected his death,” Lawson told The Times in 2004. “I don't know if he specifically expected it on that day, but he had known since Montgomery that he could be shot down ... any time.”

Wondering what kind of person would commit such a crime, Lawson began visiting the convicted killer, James Earl Ray, in prison. He came to believe, as did members of the King family, that Ray was innocent and pushed unsuccessfully for a new trial. When Ray decided to marry a sketch artist who had covered his arraignment, he asked Lawson to conduct the prison ceremony.

“It was not just that I doubted his guilt; it went far beyond that,” Lawson told historian John Egerton years later. “I knew that if Martin were alive and in my position, he would have married them even if he knew Ray was guilty. As one of my sons said to me, ‘If you believe all that stuff you’ve been preaching, you’ll do it.’

“He was right, of course.”

Lawson is survived by his wife, Dorothy Wood, and two sons, J. Morris Lawson III and John Lawson; a brother, Phillip; and three grandchildren. His son C. Seth Lawson died in 2019.

Woo is a former Times staff writer.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.