The road to Ward 17: A journalist's battle with PTSD

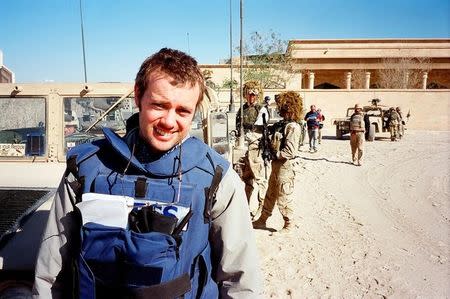

By Dean Yates EVANDALE, Australia (Reuters) - When the psychiatrist diagnosed me with post-traumatic stress disorder at the end of our first session early this March, I finally had to accept I was unwell. The flashbacks, the anxiety, my emotional numbness and poor sleep had long worried my wife, Mary. I had played down the symptoms, denied I had a problem. Five months later I’d be in a psychiatric ward. I covered some big stories as a Reuters journalist. The Bali nightclub bombings in 2002, the Boxing Day tsunami in Indonesia’s Aceh province in 2004, three stints in Iraq from 2003 to 2004 and then a posting to Baghdad as bureau chief from 2007 to 2008. From 2010 to 2012, based in Singapore, I oversaw coverage of the top stories across Asia each day. Then, after 20 years working in Asia and the Middle East, it was time to settle down. I moved my family in early 2013 to the Tasmanian village of Evandale, population 1,000, to edit stories for Reuters from home. Rather than relaxing in Tasmania, the beautiful Australian island where my wife was born, I unravelled. In a letter that was painful for her to write, Mary, a former journalist, outlined her concerns to the psychiatrist ahead of that first session: “When we came home to Tasmania three years ago it was a real ‘tree change’ for Dean and he spent much more time with the family. Very soon I began to notice changes – a loud-noise sensitivity, a quick temper, irritability, impatience, and an atmosphere of what seemed like misery that sat like a pall over the household,” Mary wrote. “I began to wonder if he had PTSD. He does say there are certain images that will remain with him for the rest of his life.” Dozens of sights, sounds and smells are indeed seared into my memory. The severed hand I nearly trod on in the wreckage of the Sari nightclub in Bali. The more than 150 bloated bodies I counted in a mosque in Banda Aceh after the tsunami. The wailing that pierced the Baghdad office on the morning of July 12, 2007, when word reached our Iraqi staff that photographer Namir Noor-Eldeen, 22, and driver Saeed Chmagh, 40, had been killed in an attack by a U.S. Apache helicopter. CALM, RATIONAL, DECISIVE PTSD results from exposure to a single traumatic event or an accumulation of traumatic experiences. The term is relatively new. It first appeared in the benchmark of modern psychiatry, the U.S. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, in 1980. That came after years of lobbying by the Vietnam Veterans Against the War organization and by psychiatrists who had treated soldiers with problems stemming from their service in Vietnam. Psychological trauma has been around far longer, of course. The term shell shock was used to describe soldiers who broke down during the trench warfare of World War One. PTSD doesn’t just affect soldiers. Police and rescue workers are at risk. So are civilians caught in war zones or natural disasters, as well as victims of sexual assault and car crashes. Most journalists are resilient despite repeated exposure to work-related traumatic events, according to research on the website of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, a project of the Columbia Journalism School in New York. But a significant minority are at risk of long-term psychological problems, including PTSD, depression and substance abuse, it adds. I never thought I’d get PTSD. I was calm, rational and decisive. I enjoyed being in charge of large editorial teams. I felt I could detach myself from tough situations when needed. But occasionally last year I couldn’t get out of bed. I’d sit at my desk in my study trying to work, barely able to lift my head. When I got stressed, I was flung back in time to our office in Baghdad, as if I had never left. I would bang my fists on the desk, scream at the walls. I was so sensitive to noise that my teenage children would freeze if they dropped something. Mary wouldn’t vacuum if I was in the room. On several occasions last year, after having read about PTSD and spoken to an expert on the condition, she told me I needed help. But when I gave in and saw a psychologist in mid-2015, he ruled out PTSD, saying I was suffering from an identity crisis because I no longer had a high-profile job and had moved to a quiet country area where no one knew me. I didn’t have PTSD, I insisted to Mary. Months later my irritability, numbness and simmering anger reached a stage where, with my marriage at breaking point this March, I finally agreed to see the psychiatrist who diagnosed me with PTSD. BUSHWALKING AND ANTI-DEPRESSANTS Without hesitation, my editors gave me three months off. I started taking anti-depressants. In the weeks after the diagnosis, I was often fatigued. In early May, I postponed my return to work to July. I did an eight-week mindfulness course through May and June, hoping meditation would help me cope with stress and anxiety. The best therapy, or so I thought, was bushwalking. In Tasmania’s rainforest I found what I was looking for – peace. I loved walking trails where I could touch ancient trees, sit by swift rivers or stare at misty mountains. I’d leave my troubled mind behind and just breathe the rainforest. I began devouring books on Tasmania’s wilderness and the history of its wild West Coast. In line with risk-taking behaviour associated with PTSD, I began planning multi-day hikes alone, in the middle of winter. Worried, my father-in-law, an experienced bushwalker, gave me his pocket-sized personal locator beacon. In the end, I took his advice and stuck to less dangerous hikes. When I wasn’t bushwalking, I was agitated, anxious and often craving solitude. In early June, when Mary said she and the children were walking on eggshells at home because of my state of mind, I raged at her, pacing around like a caged animal. Mary left the room, thinking I’d hit her if she challenged me. On June 27, I wrote in my journal: “I’m one brain snap away from a 'ledakan.'" I used the Indonesian word for “explosion,” worried that if Mary saw it in my journal, she’d freak out. The next day, I sent my editors an email saying I could not resume editing stories because it would be too stressful. My psychiatrist agreed. In July, I deteriorated. I was severely depressed. I felt like I was living in a mental fog. My nightmares worsened. In the most frightening dreams, I ran through the streets of Baghdad pursued by insurgents. On most nights, Mary said my feet were moving in my sleep, as if I was running. To get to sleep I took paracetamol and codeine tablets. I started drinking heavily. Some days I just stayed in bed. In the week before the ninth anniversary of the deaths of Namir and Saeed, I began thinking deeply about them and my actions as bureau chief at the time. I scrutinised emails I had kept from that period, asking myself if I did enough to investigate their deaths. In particular, I dwelt on the classified U.S. military video released by WikiLeaks in 2010, three years after the attack, that showed helicopter gunsight footage of them being killed along with around 10 other people. The attack came on the morning of July 12, 2007. I was sitting in the bureau “slot position” – responsible for writing the lead story of the day and manning the main phone line to regional headquarters in London. All of a sudden, a loud wailing broke out near the entrance to the two-storey house that served as our office. I knew instantly something horrific had happened. I still remember the anguished face of the colleague who burst through the door to break the news. Another colleague translated for me: Namir and Saeed had been killed. They had gone to east Baghdad after hearing of a U.S. airstrike on a building around dawn that day. As they walked down a street, they found themselves among a half dozen or so people, the WikiLeaks footage later showed, some of whom appeared to be armed. A U.S. Apache helicopter opened fire with 30 mm cannon, apparently mistaking Namir and Saeed for combatants. Namir was killed in the first wave, the footage showed; Saeed was gunned down in a second attack. The banter between the chopper pilots was shocking. “Oh, yeah, look at those dead bastards,” a pilot is heard saying. “Nice,” a comrade replies. Outwardly, I kept calm and focused on trying to find out what led to the attack, dealing with the U.S. military and consoling our staff. Compounding the bureau’s grief, an Iraqi translator working for Reuters was shot dead in Baghdad by gunmen the day before Namir and Saeed were killed. We only found out a couple of days later, when he didn’t show up for work. (The translator’s parents asked that we not reveal his name.) Inside, I was falling apart. A few days after Namir and Saeed died, I nearly had a nervous breakdown in my office. As I wept, I thought the best thing to do was resign. The stress was too much. Someone stronger needed to take over. But I pressed on. I was on holiday in Tasmania when the WikiLeaks video was released on April 5, 2010, but I felt cowardly because I had left it to others in Reuters to respond to what was a major global story, even though I felt I knew the situation better than anyone. The video, titled “Collateral Murder,” was viewed millions of times. With all this consuming me more than six years on, I reached out to colleagues I’d worked with in Baghdad, both Iraqis and foreigners, to ask what they thought. All said I had done what I could. But the guilt and shame remained. In late July, I told Mary I was desperate to find peace, any way I could. She told me I needed treatment in a psychiatric hospital, and quickly. “You’ve reached rock bottom,” she said. IN WARD 17 Two weeks later I stood outside the glass door of Ward 17, the in-patient PTSD unit at the Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital in Melbourne. I felt crippled with anxiety. I was about to cross a line, be admitted to a psych ward. “Will I emerge healthier?” I had written before boarding the flight that morning to Melbourne. “Wiser? More in control? I HAVE to for the sake of my family.” The admissions office was next to the dining room. Grizzled men covered in tattoos were finishing lunch. All had bags under their eyes. A nurse showed me to my room and asked to check my bags for alcohol. She confiscated my medication and said staff sometimes conducted random breath tests. No more rum and Cokes, I thought. Ward 17 has 20 patient rooms built around a couple of courtyards. It has a long history of treating Australian soldiers. During my five weeks there, my fellow patients included veterans of the wars in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan and the conflict in East Timor. There were male and female police officers and prison guards along with civilians who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. While not a locked facility, patients needed to sign out to go anywhere for a short time. Weekend leave was permitted. The next day I spent two hours with the psychiatrist assigned to me. What troubled me most, I said, was guilt over the deaths of Namir and Saeed. As bureau chief in Iraq, I was responsible for their safety, I said. And shame that I hadn’t stepped in to guide our coverage of the WikiLeaks video. Toward the end of the session, the psychiatrist said I was intellectualising my trauma too much and not expressing enough emotion. She said I had recounted these events as if I was describing someone else. Earlier traumas, such as covering the Bali bombings and the tsunami, had softened me up, she said. She confirmed the PTSD diagnosis, saying I was suffering cumulative trauma and also had depression. The psychiatrist changed my anti-depressants and put me on Prazosin, a medication used to reduce nightmares. She prescribed Valium for my anxiety and sleeping tablets. Back in my room, I thought, how do I deal with this emotionally? Do I just try to cry? During my stay, a social worker saw me regularly, focusing on my emotional numbness and how it had hurt my marriage and my relationship with my children. One of the goals I wrote down on the admission documents was to “find that old husband and father I used to be.” REFLEXOLOGY AND “JASON BOURNE” Group sessions covered the basics of PTSD, managing depression, anxiety and anger, and coping with sensory overload. There were classes on spirituality, mindfulness, reflexology, art therapy, even cooking. I learnt a lot from the other patients, some of whom had been to Ward 17 several times. Barriers came down fast, even though I was a journalist. What mattered was that I was a fellow sufferer of PTSD. It was validating to hear others say they had symptoms like mine, that they hated noise and crowds and had relationship problems. There were also lighter moments. During my first weekend, I thought I’d watch the movie “Jason Bourne” at a nearby cinema. Halfway there I turned and walked back to the hospital, somehow having forgotten the movie theater would be too crowded. When I later told a young nurse, he looked at me and said: “I thought you’d watch something a bit more highbrow than that.” Journalists watch Hollywood action movies too, I replied. From the first day in Ward 17, I read voraciously about PTSD or war and its impact on soldiers, reporters or civilians. I also wrote every day in my journal. As the weeks went by, I felt I was making progress. On Aug. 28, I wrote a note for my treating team: “I was cowardly when WikiLeaks released that video. I was stunned. I was shocked but I wanted someone else to deal with it. It was someone else’s problem but I should have made it my problem. That is what I have to live with.” In early September, the week before my discharge, my psychiatrist asked me to write down what I’d achieved in Ward 17. On my list: a breakthrough in honesty with Mary; starting to come to acceptance of my actions in relation to the deaths of Namir and Saeed; learning techniques to control my anxiety and stress. My goals on discharge were to have realistic expectations of the initial days and weeks after getting home, monitoring my stress levels, getting back to work gradually and staying off alcohol. I would start weekly psychotherapy sessions as well. Going home on Sept. 16 was wonderful. I was determined to reconnect with my family. Tasmania was so quiet compared to Melbourne. ONE STEP BACK Before leaving Ward 17, my treating team said recovery would be two steps forward, one step back. Sept. 23 was a “step back” day. I was in the nearby town of Launceston waiting for Mary to pick me up when a loud alarm close to the public library sounded. “Emergency, evacuate”, said a recorded voice. You’ve got to be kidding, I thought. I didn’t have my headphones. It lasted 10 minutes. Stay calm. Breathe. When I got home about mid-morning, I went back to bed. I finished reading “Dispatches,” the memoir by Michael Herr, who covered some of the major events of the Vietnam War. What those reporters in Vietnam did made me think about my time in Iraq. I was a wimp compared to them. I dragged myself out of bed to pick my daughter up from a school excursion at about 2 pm. After returning, I found that our dog had left a pile of foul-smelling diarrhoea on the floor. I started to feel myself teetering. It was another good excuse to go back to bed. Then a gardener arrived to mow our lawn. It hadn’t been cut in six weeks, so the grass was long. Instead of using a lawn mower, he took out a large whipper-snipper with a three-pronged metal blade. The noise reminded me of the little Kiowa armed reconnaissance helicopters that flitted over the Baghdad rooftops. It gave me a headache. It had been a week since I had left Ward 17. Was the honeymoon over, I asked myself? I knew I was starting to isolate myself again. I told Mary I’m having a “one step back” day but it felt deeper than that. I sensed she was worried. The next day, still feeling miserable, I went to a Buddhist temple to meditate. After sitting in the lotus position for probably 45 minutes, I got up, amazed to find my energy had returned. I then plunged into writing this story. Writing has been cathartic. In my early weeks in Ward 17, my legs would tap non-stop on the floor during therapy, a reflection of my anxiety. When I wrote, they were still. (Edited by Michael Williams)