Sheryl Crow: ‘I’m still saying exactly the same thing about guns, 30 years later’

Sheryl Crow recently took a guided magic mushroom trip with the Johns Hopkins University in Maryland. Only one thing spoiled it: the trip employed a carefully selected “playlist” designed to enhance the hallucinogenic experience. Crow’s musician’s ears took her to an analytical space instead. “The playlist robbed me of my ability to go on a mushroom journey,” she reflects sadly, in her soft Southern tones. “I thought, oh, they’re playing ‘Here Comes the Sun’, so I’m supposed to be seeing bright colours? If you don’t understand much about music, I think you can enjoy it more...”

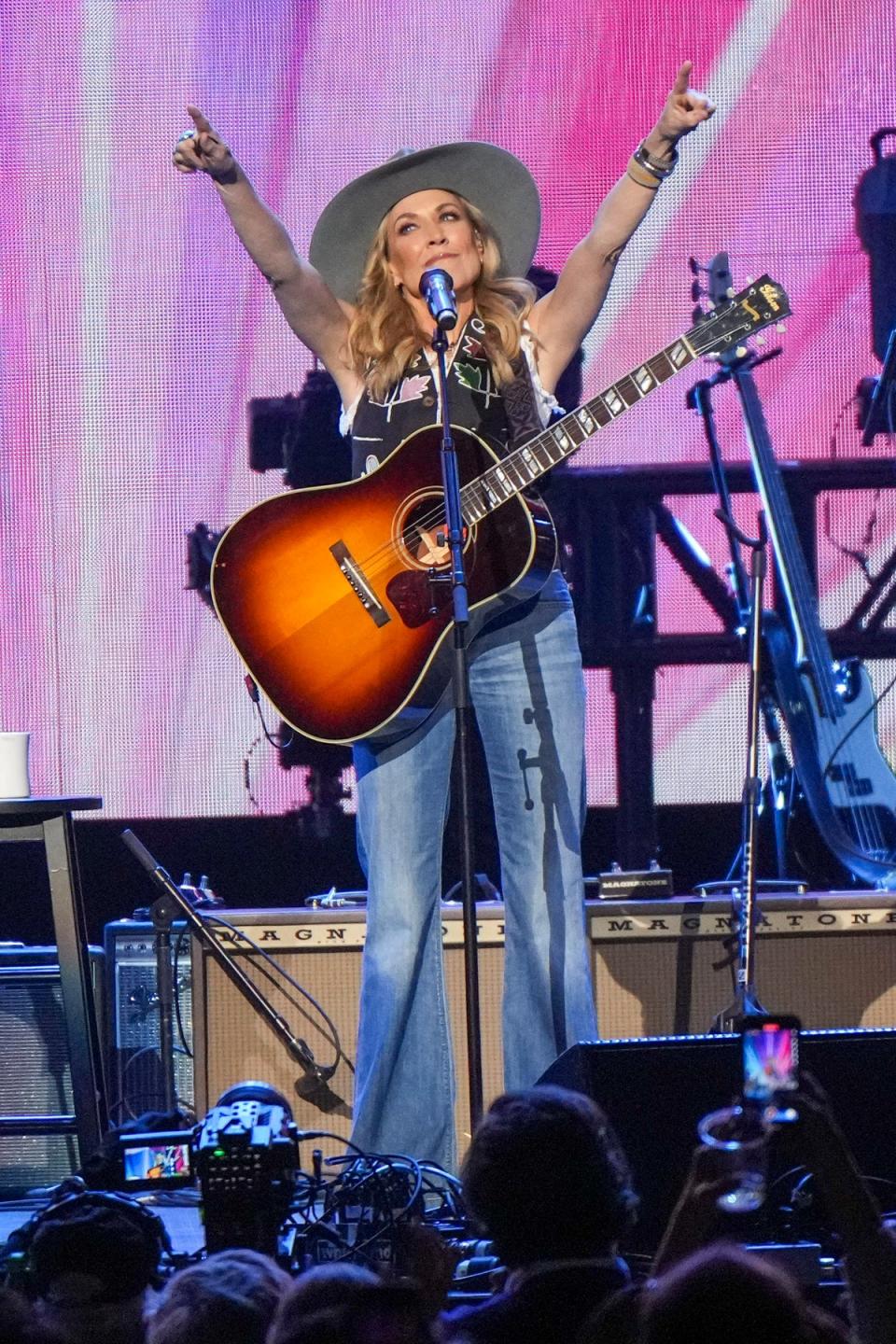

Crow, 62 (she really is 62), looks young and bright in her Nashville studio, sitting in front of four beautiful drum skins made in the 1930s that are painted with scenes of rural Tennessee life. She has many “oddities” in the ranch she shares with her two adopted sons Wyatt and Levi, whom she has raised as a single mum. She has also – she says proudly – “absolutely zero connection to the country music market as it is now”, the very industry of the town she has made her home. Her studio is above a stable (she has 10 horses), but, because it’s soundproofed, there is no snuffling or neighing to be heard on her new record, Evolution.

Actually, there shouldn’t be a new record at all. In 2019, Crow said that the star-studded Threads, which featured duets with Neil Young and Stevie Nicks, would be her last album – an eerie announcement, though she was in rude health again after a diagnosis of breast cancer in 2006 and a benign brain tumour in 2011. “I didn’t mean to make a record,” she says: she just couldn’t help it. She didn’t produce it this time: “That felt too much like going to work.” She was a music teacher in the 1980s, and still has vivid dreams that she is back in the classroom showing kindergarten children how to read notes or match pitch.

The future of music has one terrifying element right now for Crow, who has always had a social conscience. AI is coming. There’s a lot on her new record about it. She will make herself miserable reading about the stuff in the morning when her kids leave for school: “Brushing up against what artificial intelligence is going to mean in the artistic community. As an older mom, it really did jar me to think that we’re going to have to start protecting our souls’ inspiration – the difference between us and AI is that we have a soul. We have empathy, we have compassion.”

She recently spoke to a young songwriter who explained that she and her peers were using ChatGPT in their work: “You say, I want to write a song that sounds like Sheryl Crow that uses these four metaphors, then it spits it back to you. Her argument was, you wouldn’t use everything, but there’s always a good few lines in there. I thought, no, no, no, no...”

Has she heard an AI version of her own voice? “No, but you can go on any of these sites and snag somebody’s voice these days. For me it’s a broader thing,” she says. “AI is without conscience at a moment where algorithms already fortify what we feel is the truth. It’s just gonna feed us more non-truths. The album is not a bummer record, though...”

Crow’s career was launched by the 1994 slacker anthem “All I Wanna Do”, with its picaresque visions of daytime drinking and its disdain for the lunchtime carwash. There is a wonderful mirror of that song on her new record – it could, in fact, have been written by AI – complete with a Gen-X refrain, “All I know/ is wherever I go/ there I am.” Crow thinks it is melancholy. But it evokes a certain ease at one’s place in the world.

She has perhaps the perfect level of fame: four or five hits to her name, which is a lot. All the rock gods – Don Henley, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton (whom she dated) – wanted to work with her in the day, and she even wrote a Bond song, for the Pierce Brosnan era: “Tomorrow Never Dies”.

“But at my age, I can write anything I want to write because it is most likely not going to be heard,” she says. “I mean, that sounds defeatist! But there is liberation in it. You think less about who you offend. I’m not vying for spots on the radio. Being able to write about the things I see is a relief.”

Growing up in rural Missouri as the daughter of a conservative father and a liberal mother, Crow enjoyed passionate debate around the dinner table, and, as an adult, she tends to speak her mind. Never exactly cool, she complained about the violence in Pulp Fiction and Reservoir Dogs when they were the only films anyone was talking about (“I’m still saying exactly the same thing about guns, 30 years later”).

There was a dispute with Walmart when the track “Love Is a Good Thing” claimed that they sold firearms to teenagers; there was another with Michael Jackson’s camp when she accused his manager Frank DiLeo of sexual harassment in two songs on her first album (Crow spent two years as Jackson’s backing singer – the tabloids even claimed she’d been approached to have his baby).

“The interesting thing was that, back then, I would do it [speak her mind] and then I would have a thousand people saying ‘You can’t do that!’” she says. She was less angry than Alanis Morissette, less explicit than Liz Phair, less wistful than Aimee Mann; but she was a Nineties woman writing the truth of female experience long before a hashtag turned it into a movement.

“The music industry is run by men, and the reality was there was no space for anyone to talk about it, so you masked it in music,” she says. “Fiona Apple talked about it as well. Back then it was genuinely terrifying: ‘I may never get to work again if this person actually does silence me.’ Thank God we are inching along.”

Is she proud she spoke out? “I wouldn’t say proud. I guess I’ve always been true to my convictions.”

In 2020, Crow appealed to the conscience of Donald Trump in her song “In the End”, but these days, she’s given up and spreads her attention “more broadly than this one, antichrist-like person. Anyone we choose to be our leader holds aspects of what exists in all of us, and that is what terrifies me. I’ve been around long enough to know what it was like to have good leaders. But I do have hope.”

She’s been reading Neil Howe’s The Fourth Turning Is Here, about America’s cycles of rebellion, uprising and spiritual renewal. And she bemoans the lack of political writing in pop songs. “I do look to the artists I grew up listening to, Marvin Gaye and Edwin Starr and Buffalo Springfield. Songs that were actually on the radio, addressing what was happening in the world. We see it obviously in rap music now. But I find that most of what’s on the radio that I hear these days is about sex. Sex is great. I’m not saying it’s not...”

I had a moment of reckoning when I realised the stories I’d been telling myself

Crow was a born-again Christian early in life, and moved to St Louis with a fellow convert to whom she was engaged at 21. They met in an Eighties pop covers band. “God love him, he was born again but he also partied,” she recalls. “There was a cycle of drink, smoke weed, repent and repeat.” One day he told her: “If you’re not going to sing for the Lord, maybe you shouldn’t sing at all?” She chose her Huey Lewis covers instead, broke off the first of many engagements, and moved to LA, where she blagged her way into the life-changing gig with Jackson. Crow claims she knew Jackson no better at the end of two years than at the start. As her career flourished, she held on to abstract ideas of marriage and children while failing, she says, to appreciate the real-life story she was writing.

“I had a moment of reckoning when I realised the stories I’d been telling myself,” she says. “You fall in love with somebody wonderful, you get married, you have children. I don’t know what I was thinking. I wasn’t taking into account that, well, you did go to Japan and Israel and Russia all because of one song. What did you think your life was gonna look like?”

After she recovered from breast cancer in 2006, she had a life-changing conversation with her mother. “She said, ‘Be a mom. Go to a sperm bank. Adopt a baby. We’re with you.’ I realised the one person I was measuring myself against was saying, ‘Don’t do it the way I did it.’ It was like her giving me permission. But I think it was an angelic moment, because it was very not like my mom just to say, ‘Go have a baby.’ Everything got set on a course when I looked at my life and went: ‘What now?’”

It is poignant to think that a 44-year-old rock star with nine Grammy awards might still have their life changed by a mother’s blessing. Crow has built a little chapel across the driveway from her studio – she gestures over her shoulder. It contains more oddities: Spanish saints, and the taxidermy head of a deer shot long ago by a Missouri grandfather. Her own brand of spirituality has been a journey, she says: “Lots of meditation. Maybe it’s a cop-out, but it’s where I can find peace.” She loves the idea of enlightened beings, and she’s “a bit of a pantheist”. “But there are a lot of Eastern religions that preach non-attachment, and I find that next to impossible,” she says with a big, white grin. “I’m attached. I’m attached to what I see. And I worry.”

‘Evolution’ is released on 29 March. Sheryl Crow headlines Black Deer festival on Saturday 15 June