Special Report: The political battle behind the dismantling of a worker safety rule

By Julia Harte and Peter Eisler

NEWPORT NEWS, Va. (Reuters) - When Wardell Davis landed work with a Norfolk, Virginia, shipbuilding contractor in the fall of 2007, he felt lucky.

Then 24 years old, with no high school diploma, Davis had for years bounced between part-time jobs. The contractor, he says, promised better pay for grueling labor: blasting the hulls of U.S. Navy ships with coarsely ground coal particles to remove rust and paint. He recalls the fog of dust created as workers fired the crushed coal – a residue from coal-fired power plants – against the ship bottoms from high-powered hoses, moving through the tented blasting area in respirators and protective suits.

A year later, Davis found a better job with a plumbing and heating company. He became a father, but still found time to hit the YMCA most days for a swim, a lifelong passion. Then, in 2011, he began struggling to hold his breath under water; soon, he couldn’t hold it at all. He was dogged by a persistent cough, sweats and nausea.

In 2014, doctors at Norfolk’s Sentara Hospital found a “black foreign material” in his lungs. Davis successfully filed a disability claim for “pneumoconiosis/silicosis and/or interstitial fibrotic disease caused by exposure to abrasive blasting dust.” Four years and three biopsies later, Davis survives on a single lung.

Unable to work, he lives on disability payments, and has brought suit against abrasives manufacturers and safety equipment providers he alleges failed to protect him. They deny responsibility for his failing health.

“If I ever would have thought that this would have happened to me, I would’ve never ever worked there,” he told Reuters, his words punctuated by coughs. “Ever.”

Davis was one of an estimated 11,500 shipyard and construction workers who U.S. regulators say are exposed each year to beryllium: a toxic, carcinogenic element laced through the coal waste often used in abrasive blasting grits. These workers lie at the heart of a little-known regulatory drama unfolding behind the Trump administration’s push to relax safety rules it deems burdensome to U.S. businesses.

Just after the election, the Trump administration and its congressional allies began moving to unravel key provisions of a federal rule, issued in the last days of the Obama presidency, that sharply limited workplace exposure to beryllium and required certain industries to carefully monitor health risks.

Beryllium inhalation has long been known to cause lung cancer and berylliosis, a debilitating, potentially fatal respiratory illness. Yet efforts to set an updated workplace exposure standard had been stymied for decades by debates over what the new exposure limit should be. The Obama rule was based on a compromise developed by labor and industry stakeholders.

The Trump administration has left the new beryllium exposure limits intact. But in June 2017, it announced plans to exempt shipbuilding and construction operations from the rule’s “ancillary provisions,” which require air quality testing, new workplace hygiene measures and employee health monitoring for beryllium-related illnesses.

That decision, scheduled to take effect in June 2019, would remove the estimated 11,500 workers from the protections, a government analysis shows.

A 2016 U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration analysis found that the measures now being supplanted could have saved lives, estimating they would avert four deaths a year in the shipbuilding and construction sectors.

The protections would cost affected industries nearly $12 million a year, or about $1,000 per worker, according to the 2016 cost-benefit assessment. That analysis, a mandated component of the rule-making process, put the savings to society from averted deaths and illnesses at nearly $28 million, yielding a net economic benefit of about $16 million a year.

Without the benefits of the air testing and health monitoring requirements, the exposure limits for beryllium “are meaningless,” said David Michaels, who headed OSHA for seven years under Obama.

“If there’s no air testing or disease surveillance, there’s no way to know how much exposure workers are getting or who may be getting sick,” said Michaels, who now teaches at the George Washington University School of Public Health.

At the U.S. Department of Labor, which oversees OSHA, spokeswoman Amy Louviere said it would be “inappropriate” to comment for this article because the rule-making process is ongoing. The White House did not respond to interview requests.

The Trump administration’s plan to weaken the beryllium rule offers a case study in the renewed power businesses can wield in the regulatory process. In this case, emails and government documents reviewed by Reuters show, a small industry – the manufacturers of coal-based abrasive blasting grit – used a modest $270,000 lobbying campaign and well-placed congressional allies to unwind a rule a decade in the making.

“Never in OSHA’s history has the agency decided to roll back worker protections for a carcinogen,” Deborah Berkowitz, OSHA’s former chief of staff, wrote the agency on behalf of the National Employment Law Project, a nonprofit workers rights group.

The rule’s critics say its provisions for construction and shipyard operations are unnecessary because workers in those environments are already protected by other OSHA safety requirements. Extra costs unfairly fall on businesses, they say.

OSHA officials “have a mentality that there's no such thing as too much safety,” said Ike Brannon, president of Capital Policy Analytics, a consulting firm that advises businesses on regulatory issues. Previously a chief economist for several Republican congressional offices, Brannon says the beryllium rule’s construction and shipyard provisions reflect a broken regulatory system that tends to “discount” business impacts, “like lost jobs or greater compliance costs.”

U.S. Representative Bobby Scott, the new chairman of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, said in response to Reuters’ questions that the panel will investigate whether OSHA has “valid economic or scientific rationale” to eliminate the beryllium rule’s shipyard and construction provisions. The Virginia Democrat noted that OSHA has routinely included such provisions in other health standards, including a rule on toxic silica dust. By killing those provisions for beryllium, he said, “the Trump administration has created a double standard.”

Political push

More than a dozen lawmakers ultimately took up the fight to get the ancillary provisions stripped from the rule. All are Republicans, mostly from districts with shipbuilding or abrasives manufacturing operations.

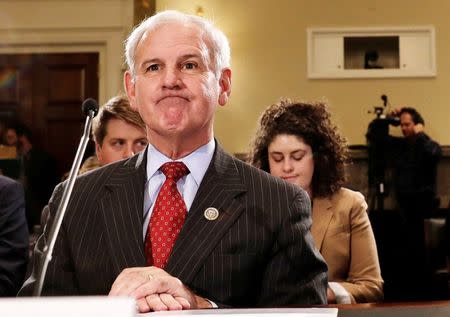

Leading the charge: U.S. Representative Bradley Byrne of Alabama, a member of the education and workforce committee who chaired its Subcommittee on Workforce Protections until the Democrats took over the House of Representatives this month.

Byrne opposed the provisions out of concern they would kill jobs at Gulf Coast abrasives manufacturing companies, spokesman Seth Morrow said. “Any additional costs could result in layoffs,” he said. In a March letter to administration officials, Byrne noted that the abrasive blasting industry employs more than 400,000 people.

The beryllium rule was the last major action OSHA took as the Obama administration wound to a close: It was published January 9, 2017, just 11 days before Trump was sworn in. Lobbying for its repeal began almost immediately.

On March 21, 2017, the new administration announced it would delay implementing the beryllium rule in light of “substantive concerns” raised about its effect on the shipyard and construction industries, said a notice published in the Federal Register and signed by then-acting OSHA Administrator Dorothy Dougherty.

Dougherty, who retired from the agency in June 2017, declined to comment. OSHA provided heavily redacted versions of her emails to Reuters, which sought them under the Freedom of Information Act. The agency has failed to respond to Reuters’ FOIA requests, filed more than nine months ago, for emails from other senior officials involved in the decision.

Dougherty’s notice referenced just one name as the source of OSHA’s concerns about the ancillary provisions: Alabama’s Byrne.

On March 13, Byrne had sent a three-page letter to the Labor Department and Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney, whose agency oversees all regulatory proposals by federal agencies, urging them to scrap the beryllium rule’s ancillary provisions for shipyard and construction operations. The letter sprang from meetings with two abrasive manufacturers in his district, spokesman Morrow said.

Both of the manufacturers – the 11-employee Mobile Abrasives Inc and 12,000-employee Harsco Minerals – were members of an industry group, the Abrasive Blasting Manufacturers Alliance, that paid lobbying firms Nixon Peabody and Squire Patton Boggs $270,000 to try to block the safety requirements.

The ABMA’s opposition centered on how the rule would affect the market for the coal-based abrasives its members produce. In comments submitted to the Federal Register by Squire Patton Boggs, the alliance said the rule would incentivize employers to switch from coal-based abrasives to alternative blasting materials, without any safety benefit. Harsco referred questions to the ABMA, which declined comment.

Byrne’s letter was submitted the same day as those comments. It included passages that were nearly identical to what the Alliance said, in some cases word for word. Other language in Byrne’s letter was nearly verbatim to an article published by a scientist employed by Harsco in an industry news publication five days earlier.

Former Patton Boggs senior partner Mark Cowan, a lobbyist who served on Trump’s Labor Department transition team, also became involved. On March 7, Cowan, who served as deputy head of OSHA under President Reagan, attended a meeting at the Labor Department, where Squire Patton Boggs lobbyists asked agency lawyers about OSHA’s plans for the beryllium rule. Cowan later wrote an essay arguing that, thanks to existing safety rules, the workers “were never threatened by beryllium exposure to begin with.” Neither Cowan nor Squire Patton Boggs replied to interview requests.

GOP opposition mobilizes

Hours after OSHA announced the beryllium rule delay on March 21, 2017, Byrne sent another letter to the agency. This one was organized with Virginia Republican Rep. Robert Wittman, then-chairman of a House subcommittee overseeing Naval programs and infrastructure, and co-signed by 14 other congressional Republicans from the House and Senate. The letter thanked OSHA for the delay but urged it to issue a new beryllium rule that did not include the ancillary safety provisions for the shipyard and construction industries.

That same day, Byrne’s re-election campaign received $5,000 in contributions from the Associated Builders & Contractors, an industry group that supports scrapping the ancillary provisions. Byrne, Wittman and others who signed the letter have drawn financial support for years from the contractors and other industry groups with a stake in the rule, including the Shipbuilders Council of America, which donated $5,000 to each lawmaker in the 2017-18 election cycle.

Morrow said the two groups had made other donations to Byrne, and that there was no correlation between the donations and beryllium rule. Asked about the donations, Shipbuilders Council of America President Matthew Paxton said worker safety is “the top priority of our industry” and that the council is part of a safety alliance with OSHA. The Associated Builders & Contractors did not respond to interview requests.

On May 15, Harsco employees and Cowan attended another meeting at the White House’s Office of Management and Budget. Seventeen days later, OSHA announced a second delay in the rule’s implementation. And on June 27, OSHA announced its proposal to revoke the safety requirements entirely.

Virginia’s Wittman joined Byrne in raising concerns because he “believed the initial rule could cause potential job loss,” his office told Reuters. OSHA, his office said, needed to reassess “the over-reaching rule.”

Mobile Abrasives Chief Financial Officer Matthew Serda told Reuters he did not fear losing jobs. Instead, he said, he sought Byrne’s help to lift the “frivolous” requirements for the shipyard and construction industries because they would disincentivize those companies from buying coal slag. That could compel manufacturers to switch to costlier abrasives such as glass and garnet.

The abrasive blasting industries are already heavily regulated, Serda said.

“Twenty years ago, when workers were wearing bandanas, yes, it may have been necessary. Nowadays they’re wearing all kinds of protective equipment,” he said. “I just have not seen anyone contracting beryllium disease from coal slag in the 20 years I’ve been working around it.”

When OSHA initially announced plans to revise the beryllium rule, it said its previous analyses had not accounted for “compliance with [personal protective equipment] and housekeeping provisions” already required at shipyards and construction sites.

That argument ran against decades of OSHA protocol, which held that if significant risk of exposure to a hazardous substance cannot be completely eliminated, “ancillary provisions” are necessary beyond existing protective equipment, said Jordan Barab, former deputy assistant secretary of OSHA under Obama.

Morrow, the spokesman for Byrne, said there are no known instances of beryllium-related illness in the shipbuilding and construction industries.

That point comes with an asterisk: No one is officially checking for such illnesses, say dozens of occupational health specialists and worker safety advocates interviewed by Reuters. The symptoms of berylliosis – shortness of breath, a persistent cough, fatigue – are similar to those of some other diseases. As a result, diagnosing the malady requires a specific blood test that just a few laboratories in the country perform, said one of the labs, the National Jewish Health Advanced Diagnostics Laboratories. They cost about $300 per person, the lab says.

The nonprofit Center for Construction Research and Training, a research arm of North America’s Building Trade Unions that has partnered with OSHA to educate construction workers about health hazards, has researched beryllium exposure. In a series of studies, it found airborne beryllium concentrations of more than 40 times the new permissible exposure limit during coal slag abrasive blasting operations. Other studies by groups including the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found beryllium-related health problems in various construction trades.

Lee Newman, a beryllium researcher at the University of Colorado, Denver, said he has treated construction trades workers who did demolition work and went on to develop berylliosis. Berylliosis “definitely” afflicts such workers, he said.

“To say otherwise is to ignore the published science on the subject,” Newman said.

Confounding illness

Shipyard and construction workers have sought treatment for lung ailments through the Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics, a network of some 60 clinics specializing in laborer illnesses and injuries.

“So many of these cases probably were beryllium disease, but nobody’s ever going to know,” said association Executive Director Kathy Kirkland. Since occupational clinics are equipped to treat common worker ailments, but not to test workers’ blood for beryllium specifically, it is impossible to know how many cases were misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis or other pulmonary diseases.

At the Newport News shipyard, a beryllium education campaign is underway, driven by local union leaders such as Allen Harville, former safety chairman of United Steelworkers Local 8888. At a recent town hall, Harville explained the berylliosis symptoms to a hall of shipyard workers.

Wardell Davis said he wishes his employer had told him about the health risks posed by coal slag and given him a chance to get his blood tested for beryllium 10 years ago. He now prepares for more tests while pushing ahead on the 2016 lawsuit he filed alleging abrasives manufacturers and safety equipment providers failed to protect him. His suit, pending in Newport News Circuit Court, seeks damages from more than a dozen companies.

Temporary laborers like Davis, who don’t belong to a union, are most likely to encounter beryllium exposure, said Chris Trahan Cain, director of safety and health at North America’s Building Trades Unions.

Large, unionized construction companies are shifting away from coal slag-based abrasives in favor of alternatives, Cain said. Smaller companies that often employ immigrant workers remain likelier to use them.

“My concern is that it’s the most vulnerable workers,” she said.

(Editing by Ronnie Greene)