The story of Shapist: how a digital game can be as tangible as a physical object

Ori Takemura is co-creator of Shapist, a puzzle game that blew our mind with its simplicity and beauty. He is also not Japanese, though his name might suggest otherwise. This is the story of how Shapist, originally a side project between Takemura and one Dmitry Kurilchenko, came to life.

28 year old Takemura comes from Moscow, Russia. He went on to study in Italy before finding himself in Singapore, where he is now happily married to a local illustrator. It was Takemura’s passion for product design that brought him to Singapore’s shores, where he ended up settling down and registering his design studio, Qixen-P Design, as a business.

But how does a design studio move into game production? Takemura says he made games back in high school, games he describes more as “student projects” than indie games. There was a gap of about a decade before he returned to his love, and that was because he realized, after many years of working for clients, that he wanted to pursue his own passions a little more. “And that was games,” he says.

The official Team Shapist photo. Ori Takemura on the left and Dmitry Kurilchenko on the right.

Shapist is not the first game Qixen-P Design has put out. The studio’s first foray into iOS game apps was Life on the Ball, which game out in 2012. It told the story of a boy who has to balance on a ball. Though it is no longer available on the App Store, Life on the Ball was a huge learning experience for Takemura and its co-creator, his wife.

They picked the wrong engine for the game, resulting in performance issues in the app. They had trouble with the difficulty curve, and with the game’s controls. They didn’t do enough play-testing, testing the game with only ten people. “But it was a good start to build upon,” Takemura says. When he began work on Shapist, he tried to address all the mistakes he had made with Life on the Ball.

While all that Takemura learnt from Life on the Ball started him off right, he was faced with different challenges. Because of the game’s nature as a puzzle, he didn’t want it to have layers.

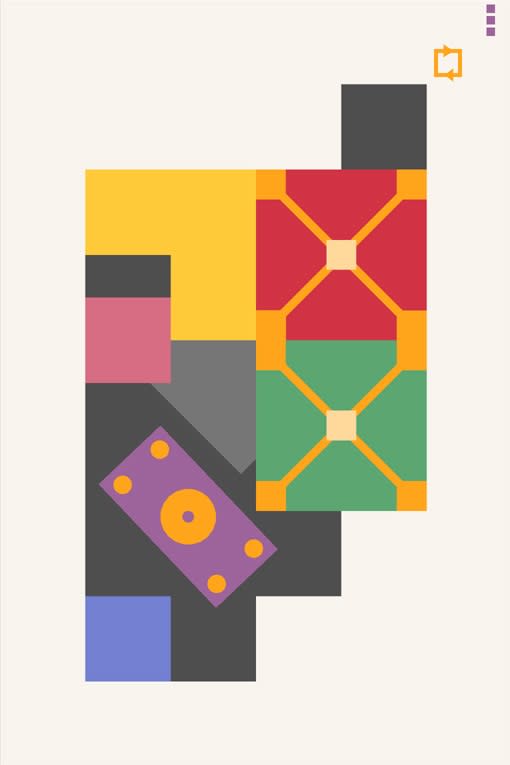

This is all you see on your screen. Shapes.

“Menus are like subtitles in a movie,” he explains. “If there are subtitles, there’s a layer in between. If you read it, there is a layer between you and the movie. In games, if there is a score bar, there’s a layer in between you and the experience.”

“For some games, you do have to have them,” he says. “But when you have a puzzle, and it’s a very physical puzzle based around sliding mechanics and moving with your fingers, I saw a real potential to completely escape this layer.”

And because there could be no layers, there could be no words or numbers or menus. Takemura was left wondering how he could educate players, or explain to them how to choose a level. “But we kept soldiering on,” he said.

The result is the $2.99 app you see today. When we first reviewed it, we didn’t think it was worth the money. “I don’t believe it warrants such a price tag,” our review said. But Takemura feels otherwise.

“It’s my passion for product design going digital,” Takemura explains, describing Shapist as a “united” experience. “No numbers, no menus,” he says. “You just play.” It is as wholesome and self-contained an experience as you can get from a puzzle game. More than that, Takemura sees it as something physical. “I want players to buy it as an object, like a Rubik’s cube,” he says.

A digital Rubik’s Cube?

Hang on, just how does this work? A digital game isn’t the same as a physical object, is it? Shapist, Takemura explains, is about a journey. “There’s a story in Shapist,” he says. During our interview he whips out his iPad, wipes off the dust that has collected on its screen, and eagerly scrolls through the levels to explain what each mean.

The third chapter, for example, has a color palette inspired by Singapore. There’s a lot of art in this game inspired by Singapore, a place Takemura has come to feel at home in. He lives in the vicinity of a heartland wet market, and the place is alive with color that can be seen in Shapist. But that’s not to say he has forgotten his roots: the summer countryside of his Russian childhood features in Shapist, too.

More important than the colors is the concept. Takemura believes that the beauty of puzzles doesn’t lie in their mechanics, but in their level design. “True puzzles don’t need physics,” he said.

There is a very simple write-up on the Shapist website. “There are no words,” it reads. “No punishment. No tutorials. No time limits and no scores…Just you and over 50 puzzles to solve.”

A Rubik’s cube had no timer. It had no scores. Neither did any physical game of fifteen puzzle. It was just you and the puzzle, and that is the sentiment Shapist conveys. Don’t believe it? Then you must try it.

Shapist is $2.99 on the App Store, and for iPad only.

The post The story of Shapist: how a digital game can be as tangible as a physical object appeared first on Games in Asia.