String of earthquakes rattles L.A.: Are they telling us something bigger?

Southern California was recently rattled by several small earthquakes. They produced minor shaking but nonetheless left psychological aftershocks in a region whose seismic vulnerabilities are matched by our willingness to put the dangers out of our minds.

For many, it all added to one question: Is this the beginning of something bigger?

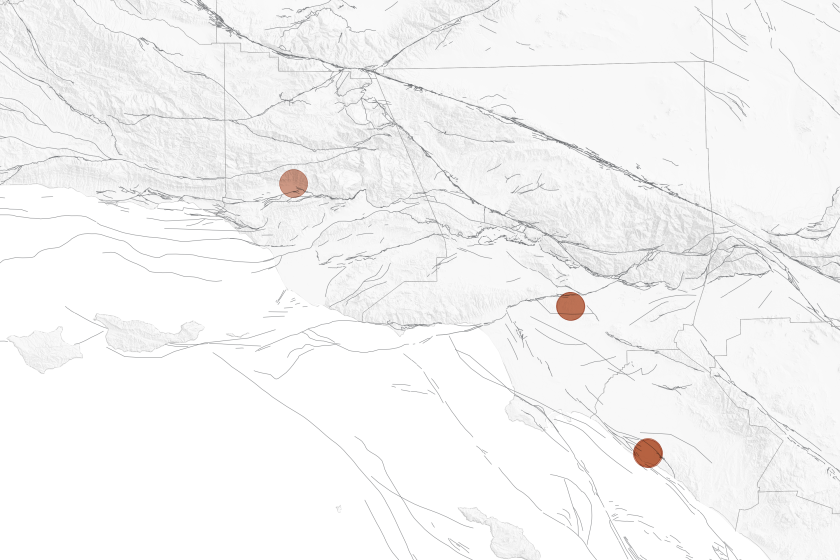

First, a magnitude 3.6 earthquake in the Ojai Valley sent weak shaking from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles on May 31. Then came two small quakes under the eastern L.A. neighborhood of El Sereno, the most powerful a 3.4. Finally, a trio of tremors hit the Costa Mesa-Newport Beach border, topping out at a magnitude 3.6 Thursday.

Having half a dozen earthquakes with a magnitude over 2.5 in a week, hitting three distinct parts of Southern California, all in highly populated areas, is not a common occurrence.

But experts say these smaller quakes have no predictive power over the next major, destructive earthquake in urban Southern California, the last of which came 30 years ago.

Read more: Faster alerts for California megaquakes: Early-warning system gets major upgrade

Generally speaking, there is a 1 in 20 chance any earthquake in California will be followed by one that's larger, said Susan Hough, a seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Those odds aren't high, and typically, the subsequent, larger quake would occur in the same area within a week. Plus, if something bigger did happen, the odds are a new temblor would be only a little bigger, Hough said.

Still, the recent quakes are a reminder that Southern California is uniquely and deeply vulnerable to earthquakes directly under us. The risk is by no means limited to the region's most famous fault, the southern San Andreas, which, apart from running under San Bernardino and Palmdale, is mostly beneath remote deserts and mountains but is capable of a magnitude 8 quake.

In contrast, last week's earthquakes highlighted nearby fault systems directly under our most populated cities and could produce even worse death tolls than a San Andreas megaquake, targeting our oldest neighborhoods with many unretrofitted buildings when they rupture.

"All three sets of these earthquakes occurred near large, potentially dangerous faults," said James Dolan, an earth sciences professor at USC. "The L.A. urban fault network has been in a seismic lull for the entire historic period, and this lull likely extends back on the order of the last 1,000 years. We know at some point this lull we’re in will end."

While some cities and government agencies have taken impressive steps to protect infrastructure, such as ordering retrofits of older buildings, many others have not, pushing off seismic vulnerabilities that eventually will come to light.

Here's a look at some of the major fault systems near the recent earthquakes that often are overshadowed by the region's more famous faults:

Puente Hills thrust fault

A three-dimensional mapping of last week's El Sereno quakes under the Earth's surface found they were just beneath the plane of the Puente Hills thrust fault, a terrifying fault that has received far less attention than the San Andreas but is capable of generating catastrophic shaking.

A magnitude 7.5 quake on the Puente Hills fault — which runs under highly populated areas of L.A. and Orange counties — could kill 3,000 to 18,000 people, according to the USGS and Southern California Earthquake Center.

That's worse than the hypothetical death toll of 1,800 people from a plausible magnitude 7.8 earthquake that begins on the southern San Andreas fault near the Mexican border and unzips all the way to the mountains of L.A. County.

"This is a very, very large fault, located in about the worst possible place you could imagine for a fault beneath L.A.," Dolan said.

The Puente Hills thrust fault was discovered only recently — in 1999 — by John Shaw of Harvard University and Peter Shearer of Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, who concluded that the 1987 Whittier Narrows quake, which killed eight people, ruptured a small portion of this fault.

The Puente Hills thrust fault is particularly worrisome when it ruptures in its entirety because of what's on top of it — downtown Los Angeles, which has many old and unretrofitted buildings, as well as broad swaths of southeast L.A. County, the San Gabriel Valley and northern Orange County.

"This thing is enormous," Dolan said.

The fault is like an angled ramp deep underground — deepest along the 210 Freeway corridor, where it is about 10 miles deep, and shallowest about a mile south of USC, where it is 2 miles under the surface.

This orientation is particularly bad if the entire fault ruptures because the shaking would commonly begin at the deepest end and move to the shallowest — meaning the shaking energy would likely move from the suburbs of the foothills toward downtown.

"Where's all that energy ... going to end up? It's going to end up at the top of the ramp," Dolan said. "That, unfortunately, is right in the core of the L.A. metropolitan region."

The shaking also will arrive at the edge of the Los Angeles Basin, a 6-mile-deep, bathtub-shaped hole in the underlying bedrock filled with weak sand and gravel eroded from the mountains and forming the flat land where millions of people live. The area stretches from Beverly Hills through southeast L.A. County and into northern Orange County.

When earthquake energy is sent into these sedimentary basins, Dolan said, it amplifies the intensity of the shaking — perhaps 10 times worse than if someone were on bedrock — and also causes shaking to resonate like a bowl of Jell-O, extending the duration.

"So the Puente Hills thrust is both, in terms of its location and its geometry, a particularly dangerous fault for Los Angeles," Dolan said.

There is one silver lining: Unlike the San Andreas fault, which generates a big earthquake on average every 100 years or so, the Puente Hills thrust fault generates big quakes only every couple of thousand years, Dolan said.

Read more: Unshaken

Compton thrust fault

Last week's Newport Beach-Costa Mesa earthquakes were close to two fault systems, one of which is the Compton thrust fault.

The discovery of this fault in 1994, by Shaw of Harvard and John Suppe, then of Princeton University, was once controversial, Dolan said, but there is now evidence not only that it exists, but that it is active.

"It's produced six earthquakes over the past 12,000 years or so," Dolan said. "These earthquakes were all in excess of magnitude 7."

A major concern when the Compton thrust fault ruptures is that the center of the L.A. Basin would be pushed up and to the southwest. That would mean the Los Angeles River, which runs from the mountains to the ocean, would start running backward around where the fault lifted the land.

"If you uplift the downstream part of the L.A. River by 5 feet in one of these Compton blind thrust earthquakes, well, the river is going to flow backward," Dolan said. So will every other plumbing system that uses gravity, from fresh water to sewer systems.

When major quakes occur on either the Puente Hills or Compton thrust faults, swaths of land will suddenly be jutted skyward, and that lift will create a trail of destruction perhaps 100 feet wide and 30 miles long. A similar zone of destruction — resulting in what is known as a "fold scarp" — was observed after the magnitude 7.7 earthquake that struck Taiwan in 1999.

"Think about what happens to every single building and every piece of infrastructure that's built across that 30-mile length, where things are going to be tilted several degrees permanently," Dolan said. "Every single building that is built across that is going to have to be torn down."

The Newport Beach-Costa Mesa quakes also occurred near the Newport-Inglewood fault, which caused the 1933 Long Beach earthquake.

Read more: Two sets of earthquake swarms have hit California. What's going on along the Mexico border?

Transverse Range thrust fault system

The May 31 Ojai Valley earthquake was in the same general area as the magnitude 5.1 quake on Aug. 20 — notable because it struck the same day Southern California was bracing for the arrival of Tropical Storm Hilary.

Both quakes occurred along the Transverse Range thrust fault system — what Dolan describes as "an extremely complex system of numerous large east-west trending faults" that built the mountains in the area. The system begins at the Cajon Pass and extends west through the San Gabriel Mountains, the Santa Monica Mountains, the Topatopa Mountains and the Santa Ynez Mountains all the way to Point Conception, west of Santa Barbara.

The Channel Islands are the tops of mountain ranges that are mostly underwater now but were built by large thrust faults across the Transverse Range system.

About 10 years ago, San Diego State professor Tom Rockwell and his colleagues made a notable discovery: Around 900 years ago, a major earthquake on the Transverse Range system uplifted the beach around Pitas Point — between Ventura and Santa Barbara — almost 30 feet. That kind of action can be explained only by "very large magnitude earthquakes, typically well in excess of magnitude 7.5 and possibly in excess of magnitude 8," Dolan said.

And it wasn't the Ventura-Pitas Point fault alone that could've done that; that fault was too small. The only way to explain such vast displacement is the linking of other faults "to generate earthquakes that would be much larger than if they ruptured just by themselves," Dolan said.

Read more: Are you oblivious to L.A. earthquakes? Here's why you might be a 'never-feeler'

L.A.'s bargain with tectonic forces

Southern California's beauty is also shaped by the same seismic forces that generate earthquakes.

The San Andreas fault, with its odd bend north of the Los Angeles area and the movement of the Pacific plate relative to the North American plate, forced the creation of numerous east-west mountain ridges, including the Santa Monica Mountains.

Earthquake faults also help explain why L.A. is where it is today — one of the largest cities in the world not centered on a navigable waterway.

In the oldest part of Los Angeles, there used to be a source of freshwater just above the old pueblo. Its location, Dolan said, was caused by the Hollywood fault, which forced groundwater otherwise hidden to flow up and over a bedrock ridge, a key perennial source of fresh water.

Quakes helped position L.A. where it is today, but they also threaten its future. And each of the three thrust fault systems near last week's earthquakes will certainly rupture again. Seismic lulls like the one we're currently enjoying tend to "end with clusters of large-magnitude quakes," Dolan said.

"We know these big faults have generated very large earthquakes in the past, and will do so again in the future," he said.

"These little earthquakes we’ve been having near these big urban faults serve as a useful reminder that we need to prepare ourselves for the inevitable future seismic storm, the likes of which hasn’t occurred in L.A. in at least a thousand years."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.