The secret deportations: how Britain betrayed the Chinese men who served the country in the war

On 19 October 1945, 13 men gathered in Whitehall for a secret meeting. It was chaired by Courtenay Denis Carew Robinson, a senior Home Office official, and he was joined by representatives of the Foreign Office, the Ministry of War Transport, and the Liverpool police and immigration inspectorate. After the meeting, the Home Office’s aliens department opened a new file, designated HO/213/926. Its contents were not to be discussed in the House of Commons or the Lords, or with the press, or acknowledged to the public. It was titled “Compulsory repatriation of undesirable Chinese seamen”.

As the vast process of post-second world war reconstruction creaked into action, this deportation programme was, for the Home Office and Clement Attlee’s new government, just one tiny component. The country was devastated – hundreds of thousands were dead, millions were homeless, unemployment and inflation were soaring. The cost of the war had been so great that the UK would not finish paying back its debt to the US until 2006. Amid the bombsites left by the Luftwaffe, poverty, desperation and resentment were rife. In Liverpool, the city council was desperate to free up housing for returning servicemen.

During the war, as many as 20,000 Chinese seamen worked in the shipping industry out of Liverpool. They kept the British merchant navy afloat, and thus kept the people of Britain fuelled and fed while the Nazis attempted to choke off the country’s supply lines. The seamen were a vital part of the allied war effort, some of the “heroes of the fourth service” in the words of one book title about the merchant navy. Working below deck in the engine rooms, they died in their thousands on the perilous Atlantic run under heavy attack from German U-boats.

Following the Whitehall meeting, in December 1945 and throughout 1946, the police and immigration inspectorate in Liverpool, working with the shipping companies, began the process of forcibly rounding up these men, putting them on boats and sending them back to China. With the war over and work scarce, many of the men would have been more than ready to go home. But for others, the story was very different.

In the preceding war years, hundreds of Chinese seamen had met and married English women, had children and settled in Liverpool. These men were deported, too. The Chinese seamen’s families were never told what was happening, never given a chance to object and never given a chance to say goodbye. Most of the Chinese seamen’s British wives would go to their graves never knowing the truth, always believing their husbands had abandoned them.

It was only decades later, with the declassification of HO/213/926, and painstaking investigations by some of the seamen’s adult children, in archives in London, Shanghai and New York, that parts of this dark chapter of British history would gradually come to light. But the children of the deported Chinese men have had no official help in this immense task – and, 75 years later, there has been no government acknowledgment, no inquiry and no apology.

“We were of little consequence,” Yvonne Foley, the daughter of Shanghai-born ship’s engineer Nan Young, told me the first time we met, over tea in a London hotel lobby in January 2019. Foley was born in February 1946, and it was not until 2002 that she began to discover what had really become of her father. “We were a blip,” she said, “no big deal in Whitehall.”

* * *

By most reckonings, Liverpool has the oldest Chinese community in Europe. At the root of this relationship was the shipping group Alfred Holt & Company, founded in Liverpool in 1866, and their major subsidiary the Blue Funnel Line, whose cargo steamships connected Shanghai, Hong Kong and Liverpool. Alfred Holt & Co quickly became one of Britain’s biggest merchant shipping companies, importing silk, cotton and tea. Over time, some of the Chinese seamen settled in Liverpool, starting businesses to serve those on shore leave. Records from the turn of the century show Chinese-run boarding houses, grocers, laundries, tailors, a chandler and, in Mr Kwok Fong, even a private detective. The 1911 census shows 400 Chinese-born residents, with many more coming and going. By the end of the first world war, the community numbered in the thousands.

Tucked in next to Liverpool’s south docks, Chinatown was the cosmopolitan heart of a city of seafarers – the Chinese mixing not just with scouse neighbours, but migrants from Scandinavia, Africa, the Mediterranean and ports beyond. The Chinese provisioners and grocers who settled in Liverpool sold great barrels of imported plums, sacks of watermelon seeds and dried shrimps, lychees, pork bao, salt fish, beef jerky soaked in soy sauce, ginger and tofu cakes, to the expatriate community and intrigued locals. “We used to go to Low Tow’s and buy one-penn’orth of guah-gees, a kind of dried watermelon seed which had a lovely tasting nut inside,” recalled one anonymous testimony collected by local historian Maria Lin Wong in her 1989 book Chinese Liverpudlians. “He also sold ‘China beetles’. I never fancied those but most kids liked them … as I remember them, they were beetles, dried, and they used to pick the legs and shell off them – ugh!”

For most of the century, Chinese-born people in Britain were officially classed as “aliens”, the category for all non-colonial migrants, and they had to carry papers recording their status – registering with the authorities and checking in periodically, as if on probation. While many Chinese people in Britain experienced racism and hardship, that wasn’t the whole story. “Among the local people, there was quite a lot of affection for the Chinese guys, and the community that grew up around them,” said Rosa Fong, a Liverpudlian film-maker and academic. They made a strong visual impression in early 20th-century Liverpool. “All the Chinese guys used to dress up really smartly, when they were on land. They wore these great coats and trilby hats, and they looked very striking, very suave.” A 1906 report from Liverpool’s Weekly Courier reflected the suspicion and admiration that characterised attitudes of the time: the article praised the Chinese for their kindness, “tireless industry and strict temperance”, while also describing Chinatown with the squalid cliches of the opium den: “Purple shadows blur the outlines of the old houses and veil the few sauntering figures … out of the dusk loom strange figures, moving with the stiff-jointed shamble of the Orient.”

A hundred metres from where Liverpool’s red and gold Chinatown Gate stands today – it was built in 2000 and is the largest of its kind in the world outside China – is where the Blue Funnel Shipping Office once stood, and next door to it, The Nook pub. Now abandoned and graffitied, for decades The Nook thronged with Chinese seamen on shore leave. When the English landlady called time, she did so in English and Chinese. Across the road from the pub there was a club, the Southern Sky, where the seamen played games like pakapoo and mah-jong for money in the basement. Working on British merchant ships for months at a time with locally born crews, the men became part of Liverpool life, and some set up home. When their ships came back in after six or more months at sea, the seamen brought with them toys, exotic birds and Chinese slippers, and their Liverpudlian families would wait at the Gladstone Dock to greet them home.

The second world war would bring many more Chinese seamen to Liverpool. China was, in historian Rana Mitter’s formulation, “the forgotten ally”. Not only did China play a vital role in the fight against Japan in Asia, Chinese seamen also kept the British merchant navy going. Beginning in 1939, Alfred Holt & Company, along with Anglo-Saxon Petroleum (part of Shell), recruited men in Shanghai, Singapore and Hong Kong. They were to crew the ships on missions across the Atlantic, bringing essential supplies of oil, munitions and food to the UK, and escorting convoys to the front. This was exceptionally dangerous work. About 3,500 merchant vessels were sunk by Nazi U-boats, and more than 72,000 lives were lost on the Allied side.

One Chinese merchant seaman, Poon Lim, became famous for surviving 133 days adrift on a tiny raft, after his British vessel was torpedoed by a U-boat in the south Atlantic. Lim and his countrymen were hailed as firm comrades in a 1944 Ministry of Information propaganda film, The Chinese in Wartime Britain. “East met west, and liked it,” explains the film’s narrator in his finest Pathe News accent, as we are shown these new friends working as doctors, engineers and scientists, and then recovering on land in between missions, drinking tea, practising calligraphy and playing table tennis. The Chinese merchant seamen fought “shoulder to shoulder in the greatest battle of naval history, alongside their British seamen comrades. They, too, brave the torpedoes and the bombs and the mines, making history under fire … life at sea fuels a unique spirit of comradeship between the men of all nations.”

For the Chinese seamen, official British gratitude and friendship did not extend far beyond the silver screen. On Holt’s ships, they initially received less than half the basic wages of their British crewmates. Nor were they paid the standard £10 a month “war risk” bonus – even though the risk of death in the engine rooms and kitchens where most of them worked was usually much greater than on the upper decks, where you could find the British. And when these Chinese men died in battle, the compensation paid to their relatives was less.

In early 1942, the Communist-affiliated Liverpool Chinese Seamen’s Union went on strike over these disparities. Violent clashes with the police at one union meeting led to several seamen being jailed. But, in the end, they won. In April 1942, the Chinese seamen were awarded a basic pay increase of £2 a month, and the same war risk bonus as the British. That was not the end of the tensions between the seamen and their employers. By September, the Journal of Commerce was reporting, under the headline “Chinese Run Amok”, that more than 400 seamen from the RMS Empress of Scotland were due in court after allegedly using “axes, adzes, swords, daggers, heavy wooden mallets, nozzles, ship’s sounding leads and any piece of wood that could be used as a weapon” to try to free 12 of their peers who had been arrested. The reason? The 12 men had refused to do their onboard duties, in protest that they had still not been paid the war bonus.

When the war finally came to an end, surveying a militant, unionised workforce, and needing to recoup its wartime losses while competing on the international shipping market, Alfred Holt immediately slashed the wages of the Chinese seamen. This made it near-impossible to survive on shore between jobs. The new wages were “insufficient for living”, an internal Alfred Holt memo acknowledged in November 1945.

The Chinese were, the Liverpool Daily Post reported shortly after the war, a “gallant body of men whose service to the Allied cause, through the Merchant Service, is greatly appreciated”. This sense of indebtedness and comradeship was sincerely felt by many Britons.

“They were war heroes, really,” said Rosa Fong. “It all makes what happened next so tragic, and such a tremendous betrayal.”

* * *

By the end of the war, the Home Office estimated that there were about 2,000 decommissioned Chinese seamen in Liverpool. At the fateful meeting in Whitehall in October 1945, it was alleged that the seamen had “caused a good deal of trouble to the police, but it has hitherto not been possible to get rid of them”. Now that the war had come to an end and Japanese troops in China had surrendered, the Chinese coast opened up again – allowing the British government to commence, in its own words, “the usual steps for getting rid of foreign seamen whose presence here is unwelcome”. (Those “usual steps” probably refer to an earlier mass deportation: 95,000 Chinese men were recruited by Britain as non-combatant labourers and merchant seamen in the first world war. They were not allowed to settle in the UK after the war, either, and their sacrifice has likewise long been overlooked.)

The Home Office’s plan was impeded somewhat by British law: only those who had been discharged from the merchant navy because of criminal activity could be legally deported. That accounted for just 18 of the 2,000 men. Some of the other seamen had committed minor gambling and opium offences, but the Home Office admitted that these were a normal part of dockside life, and insufficient to warrant deportation.

The remaining Chinese men were denied the right to work onshore. But on its own, that wouldn’t achieve the desired result. The Home Office also needed an active plan for mass repatriation, and the help of the Liverpool immigration team, police and the shipping companies to make it happen. Following the 19 October meeting, the Liverpool immigration officers began amending the dates on the official papers that the Chinese seamen were required to carry as “aliens” – requiring them to leave the country by a specific, imminent date. That way, any men who failed to board the waiting ships voluntarily could then have deportation orders issued for violating their “landing conditions”, and be forcibly taken on board by the local police. For maximum efficiency, the Home Office signed a large batch of deportation orders and dispatched them to Liverpool that autumn, just so they were ready.

Beginning in those autumn months of 1945, the Blue Funnel repatriation ships were anchored out in the middle of the Mersey, their cargo hatches empty of the usual crates and barrels, and instead rigged up with makeshift bunkbeds. The Liverpool police and immigration officers drove around the city, in particular to multi-occupancy addresses in Chinatown, such as the Alfred Holt-run boarding houses, rounding up the men and taking them out to the anchored ships, from which there was then no escape.

In December 1945, the first two of these cargo ships departed for Saigon and Singapore. By the end of the year, 208 Chinese men had been repatriated. The operation had got off to a good start, Home Office civil servants recorded in their correspondence. Meanwhile, the Liverpool immigration officers were ramping up the hunt for the others. “It should not be difficult,” one officer wrote in a memo, “if energetic steps are taken, to weed these out of the restaurant kitchens, laundries, etc.”

Initially, the Home Office specified that the 100 or more seamen with British-born wives and children were not to be automatically deported. These men were to be “reported on individually”, presumably affording discretion to the immigration team and police in Liverpool. Although marrying a local woman did not give the Chinese men the right to British citizenship, the Home Office was aware that it did give them the right to stay in the UK. This information was deliberately withheld. On 14 November, Liverpool Immigration Officer JR Garstang had written to London that “it would be unwise … to give any indication to the Chinese that because a man is married to a British-born woman he will have a claim to domicile in the UK”. In a follow-up letter, sent on 15 December, Garstang reiterated that it was best not to give the married men “a lever in their claim for domicile”. The authorities were determined to finish the job they had started.

The secret repatriation campaign was not a placid or cooperative affair. Written records suggest that it was conducted as a manhunt. The phrase “roundup” is used repeatedly in official correspondence. An immigration officers’ report to the Home Office filed on 15 July 1946 announced that: “Two whole days were spent in an intensive search of approximately 150 Pool boarding-houses, private boarding houses and private houses.” They had “spread the net as widely as possible”, they promised, alerting police chiefs across the country to look out for Chinese seamen. The report concluded: “When the operation is completed within the next few days I shall be satisfied that every possible step has been taken to secure a maximum repatriation of Chinese.”

* * *

For all that is shockingly clear in file HO/213/926, much is still unknown. “I’m still so surprised that there wasn’t something sent out to the families,” Judy Kinnin, now 76, told me recently. “Even if it was a lie! Just to try to justify it. But they did nothing at all. My mum never heard a thing.” Kinnin’s biological father, Chang Au Chiang, was a ship’s fitter and among those deported. His name is on her birth certificate, and she has a few photos, but no memories. A family friend remembers Kinnin’s mum saying, “Oh he’s stayed out playing mah-jong, because all his clothes are still there. There’s no problem.” But he never came home. “It’s preyed on my mind recently,” Kinnin told me. “I just want to know, did he make it back to China safely, and what happened to him? I could have brothers and sisters in China, couldn’t I? It would just be nice to know.”

Where mysteries remain, it is because the British state determined that we should not know – and that wives and children would live out their lives, in some cases, their whole lives, never knowing. Beyond the official records, there are oral testimonies from older Liverpudlians, since passed away, that are now impossible to verify. Accounts of immigration wagons prowling the streets of Liverpool and seizing men by force. Of raids on Chinatown boarding houses in the dead of night. Of men hiding in cellars and attics, and others who went down to the docks to meet friends and disappeared for ever. Of home visits from covert special branch officers, to seize the deported men’s documents, as if to erase any record of them. As if the children themselves were not a record.

By the summer of 1946, the rumours had spread into some degree of local awareness about what had happened. On 19 August, under the headline “British Wives of Chinese”, the Liverpool Echo reported: “Despairing that their husbands, recently compulsorily repatriated, may never return to this country, 300 British wives of Chinese seamen who on Sunday formed a defence association in Liverpool, today sent a telegram to the Chinese ambassador appealing for his intervention on their behalf.” They were led by a 28-year-old Liverpudlian, Marion Lee. No other record survives of this defence association, or of Marion Lee. None of the descendants I have spoken to recall hearing anything about it.

Around the same time, the charismatic Labour MP for Liverpool Exchange, Bessie Braddock, attempted to take up the women’s case with the Home Office, but was rebuffed. Given that some newly married men had “probably already been repatriated”, an official wrote to her in the summer of 1946, “it might embarrass the immigration officer, Liverpool, the police and the shipping companies concerned” if they now allowed others to remain.

In the internal communication between those responsible, there was denial, confusion and attempts to shift the blame. After the newspaper article about the wives’ campaign, SE Dudley of the Home Office wrote to immigration officer Garstang, claiming that “no such enforced repatriation” of married men had taken place. Instead, Dudley claimed, the drastic pay cut and further pressure from Alfred Holt’s managers may have compelled some of them to leave. In his reply, Garstang agreed, blaming “economic forces outside our control”, and the Ministry of War Transport for not giving the Chinese men work on British ships. Perhaps, Dudley conjectured, the solution would be to allow the married men to take up some shore employment, if the Ministry of Labour did not object? It would have been a fine solution, were it not being proposed nine months after the first ships departed for the east.

By the summer of 1946, the Liverpool immigration inspectors were reporting that 1,362 “off-pay and other undesirable” Chinese seamen had been deported. Perhaps, Dudley wondered, another meeting of the relevant departments should be called at some point, to discuss the married men? “It is clear that something has to be done,” his memo concluded, in the quintessential manner of the British civil service, drawing up plans for an exploratory committee to look into the possibility of potentially addressing a problem that it was already far too late to fix.

* * *

Many hundreds of men were gone, and the women who were left behind had no choice but to try to get on with their lives. Testimonies collected by Yvone Foley from some of the children speak of incredible hardships. With the families’ primary breadwinner deported, many of the seamen’s children recall going to bed hungry, crammed into just one or two rooms, surviving on the kindness of friends. Drawing state assistance was impossible for those who had married a Chinese man, because in doing so, they had automatically forfeited their British citizenship, becoming officially classified as “aliens” themselves. Some women were also rejected by their families for having married Chinese men. Some were unable to cope, and gave their children up to care homes, or adoption. Some contemplated taking their own lives.

For many of the children, their early years were marked by poverty, racist abuse and stepfathers who were “bad in the drink”, to quote one of Foley’s interviewees. “I think especially for the boys, or rather the men, missing that father figure had a lasting emotional impact,” said Rosa Fong. “It weighed on them quite heavily. To be angry at your father for all those years, and then find out it was completely misplaced all along. And for some of them, they weren’t just losing a father, but also losing an aspect of themselves – never having that connection to their Chinese heritage.”

“This country doesn’t know the damage it’s done to kids like me,” Peter Foo told me from his home in Liverpool when we first spoke earlier this year. Foo’s father was one of the deported seamen. When he was 14, Foo’s mother and stepfather emigrated to the US, leaving him in Liverpool with his grandmother, who died shortly afterwards, leaving him in the care of his older half-brother. “So you can imagine what a brilliant life I’ve had,” he chuckled darkly, “when it comes to bloody parents.” When, as an adult, Foo learned the truth about what had happened to his father, it seemed to fit with his experience of life in the UK. “In a way I wasn’t shocked, really, because I’ve had to put up with racism all my life,” he said. “I’ve never talked about compensation, I’m not interested in money. I just want a bloody apology.”

In mid-April, Foo drove me around Liverpool’s Chinatown, and then down to the waterfront, where we parked up by the River Mersey, beneath the vast ACC Convention Centre, in between Queens Dock and Dukes Dock. We sat in his burgundy Mercedes with its personalised number plate, P3FOO, and, with a mixture of outrage, pride and droll humour, he told stories about his past. He recalled how he had appeared as an extra in The Inn of the Sixth Happiness in 1958, alongside a number of other poor Anglo-Chinese kids from Liverpool – and Ingrid Bergman. The film was based on the true story of Gladys Aylward, a British missionary in China before the second world war, and 20th Century Fox had chosen to film the Chinese scenes in nearby north Wales.

Growing up, Foo was still connected to some of the Chinese community in Liverpool – and once, when he was a young adult, an old friend of his father’s suggested he travel to Singapore and try to track him down. “I said, what am I going to go and see him for? I’m not going to go out of my way to do that if he’s done a runner. That was my attitude.” No one ever suggested to Foo that his father had been forced to leave, until it was too late. Foo later found out he had passed away in Singapore in 1979. “Do you understand how angry I am, over things like that?” he said.

Foo delved into the car boot and brought out some large folders (saved from his job as a draughtsman) stuffed with documents and photocopies: marriage certificates, birth certificates, Singapore identity papers, email printouts and photos of some of the deported seamen and their wives from the 40s, neatly posed and full of hope. “When I look at the things I’ve missed out on, by not having a father … ” He tailed off. “When I was a kid, we had nothing. But I could kick the bucket tomorrow now, it doesn’t worry me. I’ve done what I came here to do.”

It was late afternoon, and joggers, cyclists and couples passed by, enjoying the last of the spring sunshine. Occasionally, Foo would break off from talking and nudge my elbow to point out different ships coming and going – a tanker, a container ship, ferries large and small. He explained that he often drove down to the docks, of an afternoon, to watch the boats come and go. “The only reason why I’ve got an attachment to the sea,” he said, “is my father.”

* * *

With an official policy of secrecy from the Home Office, and a stoical silence from the women left behind, it was only in the 2000s, after most of their parents had passed away, that the surviving Anglo-Chinese children began to uncover the truth. The starting point for many was a 2002 BBC North West documentary called Shanghai’d. It pointed to the contents of the declassified files in HO/213/926, and spoke to two older British men, who have since died, who witnessed the Chinatown raids and saw men being dragged away to the ships.

The government’s efforts to cover up what had happened were not wholly successful. When Zi Lan Liao, the director of Liverpool’s Chinese community organisation Pagoda Arts, moved to the city in 1983 with her family, some of what had happened was known in Chinatown. “When I talked to the locals, they all said it’s a well-known thing, that a lot of Chinese people just mysteriously disappeared,” Liao said. “These histories get written out, but in the community, people knew.” The precise details, however, remained unknown.

In 2002, after seeing the BBC documentary, Yvonne Foley visited the Public Record Office in Kew to see if she could find out more. There she read the Home Office files on the deportations, and the letters between Whitehall and the Liverpool immigration officers, in which they referred disparagingly to the Chinese seamen – asserting without evidence, for instance, that “over half” were “suffering from VD or TB”. They were equally disdainful of the seamen’s wives. One of the officers told the initial meeting at Whitehall that “Some 117 of the Chinamen have British-born wives, many from the prostitute class, and would not wish to accompany their husbands to China.”

For Foley, it was this line that lit a fire in her. “That was the statement that got my gander up, and really spurred me on to find out more,” she told me. “How dare you make such a sweeping statement about these women? I’ve met some of these women – and my own mother! How dare you say that?”

It was to be the start of more than a decade of phone calls, emails, interviews and hunting through maritime records scattered across the world. There was “masses of information that had to be sorted and analysed,” Foley later wrote. “It was a detective story. A three-dimensional jigsaw.” As warm as she is in person, Foley gives a strong impression that she will not suffer fools gladly, and a stubborn perseverance that has become an asset in her long search for the truth. “You’re just like your father,” Foley’s mother had told her once. “Always arguing, wanting to change the world.”

Foley visited libraries, museums and private collections in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Dalian, Melbourne and London. She had Alfred Holt documents sent from the Netherlands, and others from the New York-based archive of Wellington Koo, the Chinese ambassador to the UK at the time of the deportations. It all helped build a vivid picture of what had happened: the desperation of postwar life, the shipping companies’ commercial imperatives, the government’s callous disregard for the people affected. At one stage Foley went to meet one of the last surviving wives in a nursing home. “She said: ‘Even at my age, it’s nice to think I might not have been deserted,’” Foley recalled.

Foley also created a website, Half and Half, to share what she found, and slowly a network of fellow children of deportees emerged. They called themselves the Dragons of the Pool. Together, they pieced together more of the story, finding solace in one another and solidarity in realising they had not been alone. “It’s nice to recognise that there’s another part of you,” Foley told me. “I think my mum would have been pleased.”

A few of the people Foley and her husband, Charles, interviewed for their self-published book, Sea Dragons, were just about old enough to remember their fathers. But those memories are hazy and dreamlike, fragments snatched from a distant past. One recalled an image of his father cooking diced potatoes in a wok. Another, his father visiting when he was a young child, and placing a folded £5 note in his hand. Another remembers a stranger, a Chinese man on a motorbike – perhaps a friend of their deported father? – turning up in Liverpool and asking after her mother, only to disappear again.

For some of the children, their early years were tough but happy. After Leslie Gee’s father, Lee Foh, was deported, the family lived in a hostel for a time. But there was still a connection to the local Chinese community and culture. A few years later, Gee’s mother remarried, to another Chinese seaman who came to Britain in a later wave of migration. “It was still hard for me mam,” recalled Gee, who is now 76. “But the Shanghainese kept together. My stepfather would take us kids down to Chinatown, we used to get taken to the Chinese cinema – we didn’t understand what they were talking about, but it was great fun. We’d watch the Chinese news, and they had the Chinese opera, it was amazing, eye-opening to see.”

There’s a philosophical response detectable in many of the surviving descendants. Their mothers had been left on their own, and they had coped with their situation by trying to shake off a difficult past and move on. Many of their children have this same stoic attitude. This was, many of them have reminded me, a very long time ago – and people didn’t talk about things like this back then. As Gee’s wife, Joan, put it: “Les’s mother was like a lot of that generation: none of your business, it’s in the past, not to be spoken about.”

Gee only began looking for his father a few years ago, he said, because his wife was keen on ancestry websites, and had pressed him into it. They discovered that Lee Foh had ended up in the US some years later, and with the help of the obliging US immigration service, they got hold of photos, fingerprints and his shipping passbook. “I was born in April ’45,” Gee said, “and his passbook ends abruptly that year. The last date printed is ‘went to sea’ in December 1945 – and that was the last we ever heard of him.”

* * *

What happened to the deported seamen when they docked in Singapore or Hong Kong, or finally made their way back to mainland China? Why didn’t they ever come back, or at least get in touch? In most cases, we simply do not know. All we know is they were returning to a country in which decades of fluctuating hostilities had finally erupted into a full-scale civil war, following the surrender of Japan in September 1945. It seems likely that many of the returning men were swallowed up by the carnage of that war – the Shanghainese Blue Funnel crew were mostly active Communists and trade unionists, making them targets for the nationalist Kuomintang – as well as by poverty, and the years of tumult that followed Mao’s victory in 1949. In later decades men from Canton signed on to British merchant vessels bound for Liverpool, and migrants would follow from Hong Kong, but it is perhaps little surprise that most of the deported men were never heard of again.

At least one of the men did make it back to Liverpool, and stayed. Perry Lee’s dad, born Chann Tan Yone in Ningbo in 1903, had served as a “donkey man” or “greaser” in the Blue Funnel engine rooms during the war. Two of his ships were torpedoed, and he spent some time in a prisoner of war camp in Germany. He was, Lee told me, forcibly repatriated sometime in 1946, leaving behind Lee’s mother, Frances, and a two-year-old daughter, his older sister.

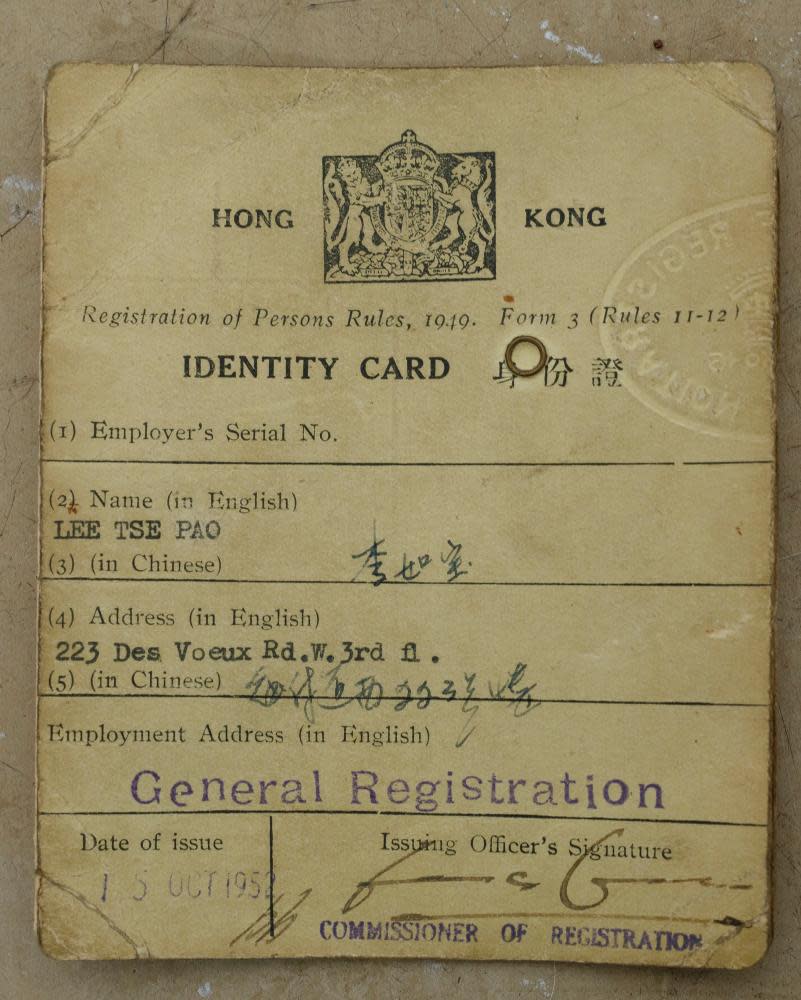

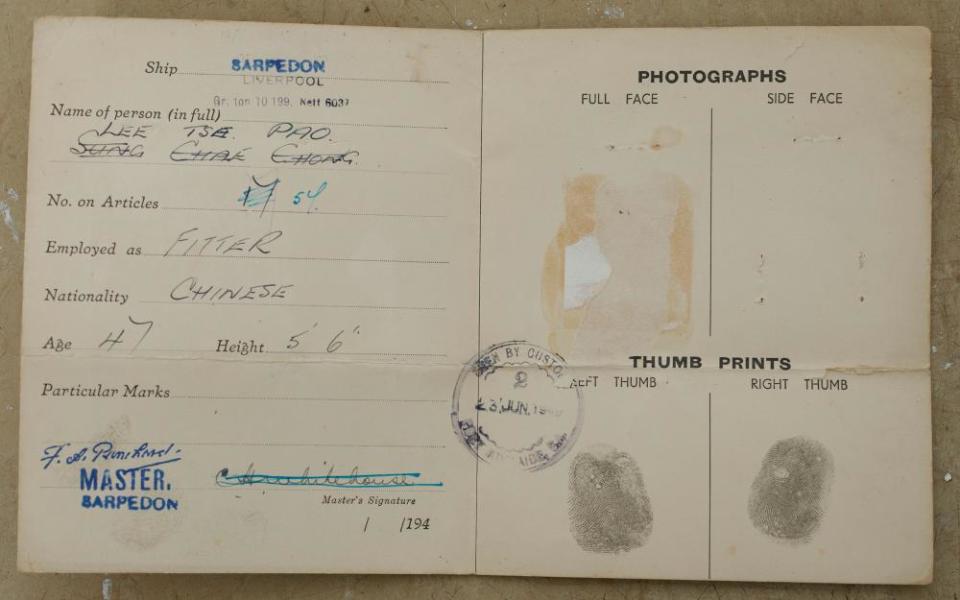

That might have been that. But three years later, Chann Tan Yone returned to Liverpool on one of the same Alfred Holt ships that had been used to deport the seamen, the SS Sarpedon. To avoid suspicion from the British authorities, he was now calling himself Tse Pao Lee. He reunited with Perry’s mother and sister in Liverpool in 1949, and, in 1952, Perry was born.

“All the things I’ve achieved in my life are down to the fact that my dad managed to come back,” Lee told me as he drove us in his converted camper van to Everton cemetery, where his father is buried. Lee is a big character, and on the day we met he wore a checked blue-grey blazer, sunglasses and a Donald Trump parody “NOPE” T-shirt in the style of the famous Obama poster. As we drove through Toxteth on our way to the cemetery, Lee narrated the history of the 1981 riots, breaking off occasionally to shout cheerful greetings and queries out of the window to strangers.

“My dad made a valuable contribution, like hundreds of thousands of other Chinese seamen, and was unceremoniously booted out,” said Lee. “He had to leave his wife and daughter – but managed to come back again. What does that say about resilience?” When, later in life, his father suffered a stroke and needed to move into a nursing home, Liverpool council placed him in a grand 19th-century mansion overlooking the city’s majestic Sefton Park. It was Holt House, built as the residence of the Holt family, owners of the Blue Funnel Line.

Eventually, after making our way through Everton cemetery to the large Chinese section, Lee spotted his father’s grave. He is buried beneath a bilingual headstone that bears his original name, Chann Tan Yone. “He told me that if he was going to die and be buried in a foreign country,” Lee recalled, “he wasn’t going to be buried in a grave under someone else’s name.”

* * *

Of all the mysteries that linger, the one that came up most often in my interviews with the children of the Chinese seamen is this: where is the list of the 2,000 names of the deportees? Surely, there must have been a document used by the Liverpool immigration inspectorate and the police in their roundups and house calls. Even after years of dogged research, the children retain a nagging sense that somewhere out there is an extra tranche of typewritten documents, gathering dust in an archive, that makes more explicit what occurred.

Maritime record-keeping is notoriously thorough: every head is counted, every inch, knot, fathom and ounce logged. In the course of researching this piece, I have unearthed sepia-coloured lists – documents known as “ship’s agreements” or “ship’s manifests” – for at least some of the deportation ships. For the SS Diomed’s departure on 8 December 1945, the manifest contains a page devoted to “Names and descriptions of ALIEN passengers”. Printed in type-script are the names of two first-class passengers, one Danish and one French. Below that, handwritten in an elegant old-fashioned cursive, as if an afterthought, the following words appear: “100 Chinese seamen shipped by the Home Office. Manifest prepared by HM Immigration Office.”

For the SS Menelaus, which departed 14 December 1945, we have the names and particulars of the 107 deported Chinese seamen, too – their dates and places of birth, “last landing’ date in the UK, and their addresses in Liverpool: the majority in Great George Street and Great George Square, Pitt Street, Nelson Street – the heart of Chinatown. Another Alfred Holt cargo ship, Theseus, departed 1 August 1946, with no fewer than 27 of the 91 Chinese seamen listed as being resident at 13 Nile Street, presumably one of the crammed seamen’s boarding houses. In December 1946, it seems that the deportations were still going: this time via the cargo ship Priam. The list of “alien repatriates” on that ship numbers 196 people: 194 men, one woman, and “baby Kenneth Ling”.

There are several references in the Home Office documents to lists of various kinds. A letter from the Liverpool police commissioner to the Home Office’s aliens department dated 9 November 1945 requests “full particulars” of those to be repatriated. Some of the Home Office meeting minutes from 1946 refer to a “nominal roll of Chinese seamen married to British born women”. For now, these details remain elusive. “We’ve searched everywhere we possibly could,” Foley said. “We could keep going, but … ” she smiled, “we’re getting old. Our aim was to get it out there, and we think we’ve done that.”

At a local level at least, there is now some awareness of what happened. In 2006, Foley got clearance from the council to place a plaque, inscribed in English and Chinese, on the pier head at Liverpool, paying tribute to the seamen and their families left behind. A representative from Alfred Holt laid a wreath at its unveiling. (Funding for the plaque came from Foley herself.) In 2015, Liverpool city council unanimously passed a motion acknowledging this “profound injustice” and calling for the Home Office to acknowledge and apologise for the deportation. Peter Foo made an emotional speech to the 200 people present. “We live with the hurt every day,” he said.

Foo has drawn up plans for a memory garden in Liverpool, with terracotta sailors, water features and a Chinese-style footbridge. Rosa Fong is hoping to make a film about the deported men. Local artists Moira Kenny and John Campbell, who have conducted extensive oral history research in Liverpool’s Chinese community, would like to turn The Nook pub into a Liverpool Chinatown Museum. None of these projects has received any serious official support, financial or otherwise.

Former Liverpool MPs Luciana Berger and Stephen Twigg made private representations to the Home Office on behalf of their constituents in the 2010s, too. Replying on behalf of the government, Conservative immigration ministers Robert Goodwill, Brandon Lewis and Caroline Nokes each rejected the idea of any wrongdoing, and pointed to the Home Office documents’ unsupported assertion in August 1946 that there had been “no forcible repatriation”, in spite of the other Home Office documents that detail “roundups” and raids – and indeed the phrase used in that first meeting in October 1945: “Compulsory repatriation”. (The irony, of course, of contemporary Tory ministers rebuffing the protestations of Labour MPs, is that it was Clement Attlee’s Labour government that deported the men – something several of the descendants mentioned to me.)

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the deportations, and the new MP for Liverpool Riverside, Kim Johnson, welcomed the lunar new year in February by calling on the Home Office to finally apologise to the families. The forced repatriation scheme was, she said, “one of the most nakedly racist incidents ever undertaken by the British government”. It was “a shameful stain on our history”, yet “barely remembered”. On 3 March in Prime Minister’s Questions, she spoke of the “lasting emotional trauma” for the children, and asked Boris Johnson to acknowledge the forced repatriations, and give a formal apology. With that day’s budget on his mind, the PM smirked about how much he loved visiting Liverpool, and breezily fobbed her off. “Her message has been heard loud and clear,” said Johnson.

“Someone asked me: ‘Why don’t you get angry about it?’” Yvonne Foley said to me in 2019. “My anger has been channelled into my research. What can you do? There’s no point in ranting and raving. None of the people responsible are around to defend themselves.” All she wants from the government of today is an acknowledgment of what happened. The journey has provided some kind of peace in itself.

“I didn’t set out to find my father,” she told me. “I set out to find the truth. But in doing what we’ve done, I’ve found him in myself, in my own character. That’s the way I’ve explained it.”

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, listen to our podcasts here and sign up to the long read weekly email here.