Mali hit by first suicide bombing

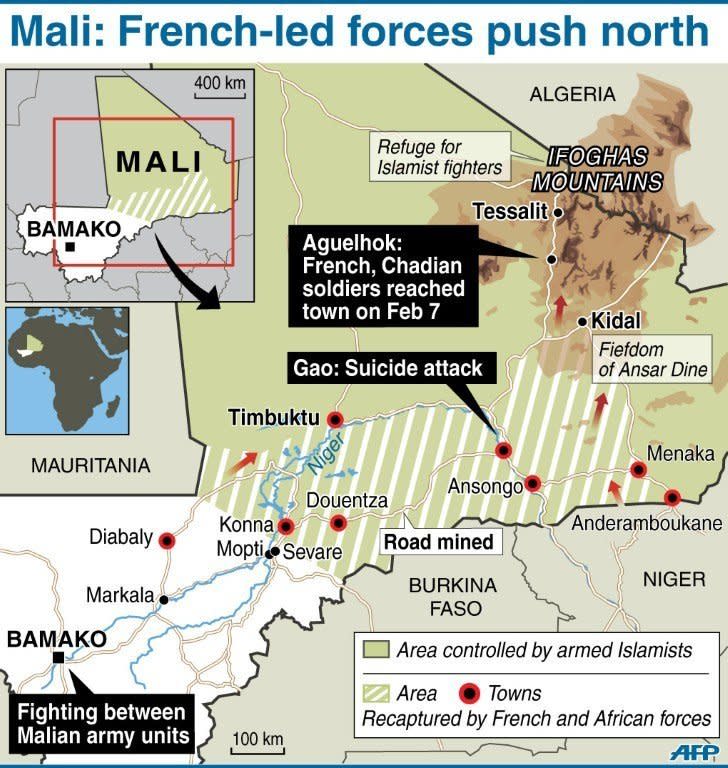

An Islamist suicide bomber blew himself up in northern Mali on Friday, the first such attack in the country, while rival factions of the Malian army clashed in the capital Bamako. The bomber rode a motorcycle up to an army checkpoint in Gao, the largest town in the north and only recently recaptured from the Islamists. He detonated an explosive belt, wounding one soldier, an officer said. It was part of a new guerrilla campaign in response to a French-led offensive that drove the extremists from their northern strongholds into the remote northeast, where troops seized the strategic oasis town of Tessalit on Friday. The young Tuareg, dressed as a paramilitary officer, was also carrying a larger bomb that failed to detonate. A spokesman for The Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) said it had carried out the bombing. "We claim today's attack against the Malian soldiers who chose the side of the miscreants, the enemies of Islam," MUJAO spokesman Abou Walid Sahraoui told AFP, vowing further attacks. MUJAO is one of a trio of Islamist groups that occupied northern Mali for 10 months before France sent in fighter jets, attack helicopters and 4,000 troops to drive them out. Despite the success of the French operation however, Mali's state and its military remain weak and divided, a situation highlighted by a gunfight in Bamako between rival troops. The firefight erupted after paratroopers loyal to ex-president Amadou Toumani Toure -- who was ousted in a March 2012 coup -- fired into the air to protest an order absorbing them into other units to be sent to the frontline. Two adolescents were killed and another 13 people wounded in the clash at the paratroopers' camp, state media said. Interim president Dioncounda Traore reprimanded the military over the incident. The fighting overshadowed the arrival of 70 EU military trainers, the first of what is to be a 500-strong mission tasked with whipping the Malian army into shape. French General Francois Lecointre, leading the mission, said there was "a real need to recreate the Malian army, which is in a state of advanced disrepair". The nation imploded last year after the coup, carried out by soldiers stung by their humiliation at the hands of fighters from the nomadic Tuareg waging a separatist rebellion in the north. A month later, paratroopers launched a failed counter-coup that left 20 people dead. With Bamako in disarray, Al-Qaeda-linked fighters hijacked the Tuareg rebellion and took control of the north, imposing a brutal form of Islamic law. France launched a surprise intervention in its former colony on January 11 as Islamist insurgents advanced towards the capital due to concerns the entire country could become a sanctuary for Al-Qaeda-linked groups. France is now anxious to hand over the operation to UN peacekeepers amid fears of a prolonged insurgency. In the latest, guerilla phase of the conflict, two Malian soldiers and four civilians have already been killed by landmines. French troops are still fighting off what Paris called "residual jihadists" in reclaimed territory. After announcing plans to start withdrawing in March, France on Wednesday called for a UN peacekeeping force to take over, incorporating some 6,000 African troops slowly being deployed. But UN chief Ban Ki-moon voiced alarm at the growing insurgency and warned it would take weeks for the Security Council to decide if it was safe enough for a UN force to move in. Continuing their advance Friday, French special forces parachuted into the airport at Tessalit, near the Algerian border in the far northeast, the army said. Along with Chadian troops, they sought to flush the Islamists out of hiding in the Adrar des Ifoghas mountains, where they are believed to have fled with seven French hostages. Former US ambassador to Mali Vicki Huddleston said in an interview that France, Germany and other Western countries had paid as much as $89 million from 2004 to 2011 in ransom money to the militants French troops are now fighting. US State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland could not confirm the figures, but said Washington was concerned Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and other groups did not use hostage taking as their main source of finance. French President Francois Hollande said there was "no question" of ransoms being paid to free the current hostages.