I Survived a Whale Attack That Left My Family Stranded in the Ocean for 38 Days

"I found myself swimming desperately in the water knowing that any second the killer whales could return and I would feel their bite," recalls Douglas Robertson

Provided by Douglas Robertson

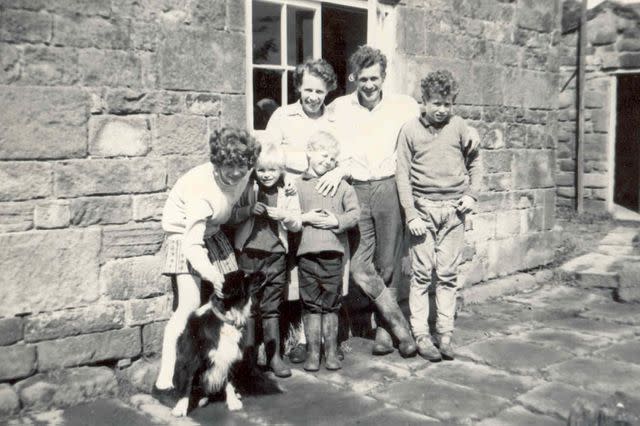

(Left) The survivors of the 'Lucette' sinking today (L-R, Neil Robertson, Douglas Robertson, Robin Williams and Sandy Robertson); (right) an archival photo of the Robertson family circa the 1971-1972 voyageIn 1968, Dougal and Linda Robertson as well as their four children — Anne, 18, Douglas, 16, and twins Neil and Sandy, 9 — were glued to radio, following British master yachtsman Robin Knox-Johnston’s attempt to become the first person to sail solo around the world non-stop. It prompted Neil to say: “Daddy's a sailor. Why don't we sail around the world, too?”

So the Robertsons sold their farm and used the money to buy a schooner, which they set sail on in 1971 from Falmouth, England. On June 15, 1972, some 18 months after the family embarked on their voyage, the schooner was attacked by three killer whales in the Pacific Ocean. It forced the Robertsons and a hitchhiker to abandon ship and seek refuge first in a raft and then later in a dinghy. Stranded for 38 days, they relied on rainwater, turtle blood and their wits alone, before a Japanese boat found and rescued them. Remarkably, no one died.

The rescue made headlines and Dougal, who died in 1992,wrote a book, Survive the Savage Sea, about the experience. Douglas later revisited the shipwreck in his 2004 book, The Last Voyage of the Lucette, Here, Douglas, now 70, recalls the entire ordeal — from the optimism of the initial voyage to finally returning to land in his own words — in his own words, as told to PEOPLE's David Chiu.

Douglas Robertson

An archival photo of Dougal and Lyn Robertson with their children Douglas, Anne, Neil and SandyIt was the summer of 1970. We bought this schooner, Lucette, in Malta, and sailed it back to Falmouth — now, 18 months after we'd made the decision to sail and sold the farm, we sat thinking, "Are we really doing to do this?"

Of course, the answer was yes, and that's what we did on January 27, 1971. We didn't even sail around the bay for a bit of practice with the yacht before we set sail from around the world. Dougal said training is best done on the job. That turned out to be shortsightedness.

Initially, that training consisted of heavy weather, close encounters with other ships and breakages, but we mostly had a fantastic time basically fishing and meeting other likeminded people. We went from Lisbon then to the Canary Islands. We inherited a life raft [from a fellow traveler], thank God, and we sailed out through the Caribbean, up through the Bahamas and to Miami, where we stayed for about six months. We worked there and saved up some money for the next leg.

Douglas Robertson

The Robertson family on the yacht 'Lucette'We left the United States in January 1972 and sailed on. My sister had decided that she wouldn't come with us any further as she'd fallen in love with a young man. It changed the boat because we were no longer a full family. We'd left one of our people behind.

We sailed onto Jamaica, through the Panama Canal, and southwest to the Galapagos Islands. We were there for three weeks before heading to the Marquesas Islands some 2,000 miles away. On the way, we picked up Robin [Williams], a student hitchhiker, in Panama.

Related: I Survived a Bird Smashing Through My Plane's Windshield and Slamming into My Head Mid-Flight

It was two days and 200 miles out from the Galapagos when on June 15 at 10 o'clock in the morning that three killer whales attacked with a bone-jarring strike. “Bang, bang, bang!” was the first thing we heard. We knew instinctively we were in trouble.

Almost immediately, I poked my head down the cockpit hatch and saw water swirling around Dougal's ankles. Our words were interrupted by a loud surging noise over my left shoulder. I looked around and there were three killer whales in close company following us: a daddy, a baby, and a mommy. And the daddy whale had his head split open and was bleeding into the water. I said, “Dad, there's whales out here.” He said, “I've got to try and fix the leak.” Even I knew that that couldn't really be done. The water was coming in too quickly. Then he said to me, “Look, we're going to have to abandon ship. Get the life raft over the side, get the dinghy over the side. I'll be with you soon.”

Our voyage of discovery turned into a nightmare. I rushed forward to take down the sails as if it would somehow delay the inevitable. I took the dinghy Ednamair and launched it over the side and with a single heave flung the 80-pound raft into the sea. The next wave washed me off the foredeck and I found myself swimming desperately in the water knowing that any second the killer whales could return and I would feel their bite.

The raft was still attached to the sinking yacht, and that's what held it close by so we could board. The dinghy held the raft back and stopped the wind from blowing it away. It also enabled us to collect some of the wreckage [from the sunken Lucette] that was floating in the water. We managed to get the sail, my mom's sewing basket, biscuits, oranges, lemons, onions and other flotsam in the vicinity of the raft. All of that took place in a few minutes.

And we were very grateful that we were still all alive and somehow made it that far. Of course, with one problem solved, we now had another because we had to try and decide what to do.

A plan was born as we were in the raft. We would sail north to the Doldrums and collect rainwater. With that rainwater, we would then set sail, towing the raft with the dinghy using the sail I rescued from the wreckage. We thought we could be in the Doldrums in a week to 10 days.

Provided by Douglas Robertson

The Robertsons on their yacht the 'Lucette'We made three promises to each other. Firstly, we said we would not eat each other no matter how bad it got. We would die quietly together if that's what it came to. Secondly, we would constantly search for a rescue ship. The third pledge was that we would not rest until we got back to land. We felt buoyed up beyond words and hopeful that there was a chance that we might survive.

Finally, on the sixth day we were adrift, a ship sailed past us and didn't see us, despite us sending up flares. It left us devastated and it changed our mindset. Dougal said, “No longer will we look for rescue. We are going to sail on this dinghy for 75 days [to America].” I said, “Dad, we can't survive in this.” And he said, “We have to.”

On the 10th day, we've arrived at the Doldrums. It didn't rain for another three days. But when it rained, it rained. And we were so happy — we sang, we laughed, we cried. We filled all our tins with water and dared think for the first that we might make it.

Six days later, we lost the raft and had to all go to the dinghy. We had terrible thunderstorms. We were so cold. We had no clothes to wear. They rotted away from us. We lost all the bloody water, so we went for five days with hardly any water at all — and that was a self-inflicted wound because we had spilled the water ourselves.

Related: I Survived a Fatal Ferry Sinking in the Bahamas. Why I’d Get on the Same Boat Tomorrow

When it rained, the water gathered in the bottom of the dinghy. But we couldn't drink that water. It was too dirty. My mum came up with this idea [of using enemas to stay hydrated]. So I made the enema tube from the rung of a ladder. I attached a funnel and then my mother administered them.

We also came up with these fantastic fish-catching contraptions. We did manage to catch turtles and found a way of drinking their blood so we could stay hydrated. We also caught dolphins, sucking their eyeballs and their vertebrae for water. Even a shark's stomach provided us with what resembled a cooked meal from the partially digested contents.

Related: I Was Internally Decapitated After a Motorcycle Crash. This Is My New Normal

I gave up at one point, and Dougal said, “Douglas don't. Do not let your bright light go out. We need you to survive so that you could help us survive.” What kept my dad and my mum going was not their own survival, but the survival of their children. My dad said, “I will not rest Linda until I get these boys on a steamer home.”

It was the 38th day [of us being shipwrecked]. We were talking about being so close to land now that it couldn't be far away and we should start rowing. But then we saw a Japanese fishing boat, Toka Maru II. We had two flares left that we'd saved from [Lucette]. Dougal cast it into the sea and said, “Well, it's all in God's hands now."

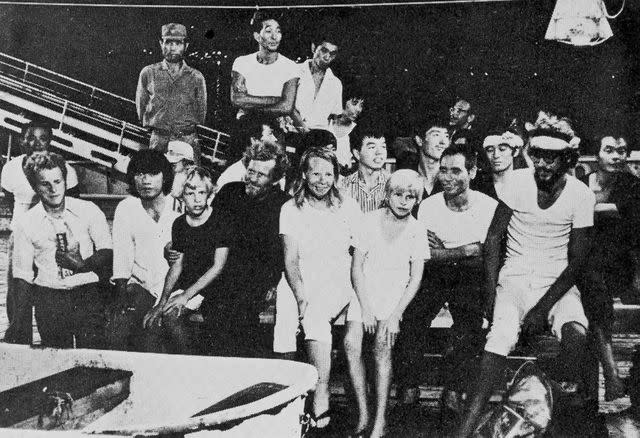

Provided by Douglas Robertson

The moment the Robertson family was rescued by a Japanese boat after being stranded for 38 days in the PacificThe fishing boat finally altered course towards us, and there was no doubt in our minds that we were going to be picked up. The ship approached and they threw a heaving line across. I grabbed hold of it. It was dirty and oily, and I loved it. I thought, “This is not from our world. This is from another world that I belong to. And if I just hang on to this bloody rope, we are going to be back to civilization very soon.”

Eager hands from Toka Maru II reached out and pulled us on board. They offered us bread, coffee and some orange juice. The captain said, “I thought you maybe have scurvy because you smelled so bad.” We bathed for the first time in six weeks.

We were very weak when we arrived in Panama, and the doctor thought we couldn't manage to fly home. Although Robin managed to fly, we went home by ship. Our strength came back and we were ready for a new life again, although we didn't know what the future held for us.

Provided by Douglas Robertson

The Robertson family following their rescue by a Japanese boat after being stranded in the Pacific for 38 daysDougal bought another yacht with the proceeds [from his book Survive the Savage Sea, about the shipwreck] in order to try and finally complete the voyage. But he never did and he settled in the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, I joined the Merchant Navy and sailed around the world three times. Our dinghy Ednamair is now housed at the National Maritime Museum in Cornwall, England.

Provided by Douglas Robertson

(L-R) The survivors of the 1972 Pacific Ocean shipwreck today: Neil Robertson, Douglas Robertson, Robin Williams and Sandy RobertsonWe had sight of a common goal and what got us through that challenging time was we worked as a team and contributed our special skills in achieving that goal. Dougal was the strategist, my mother provided the care, I provided the muscles, Robin kept our morale up, and the twins kept us honest. They reinforced the need for us to survive for their young lives.

If you just say, "Look, you were cast adrift for 38 days. Get over it. You survived" — well, that is true. But what is also true is that you keep thinking that you're going to die. You die five times a day. You don't know if you're going to make it. That changes you and makes you value life. And it is those things that make you into a stronger person.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.