Tiananmen Square witnesses remember an air of celebration, and then 'Orwellian silence'

It was mid-morning in Tiananmen Square in Beijing on 1 June, 1989. Someone had turned on a boombox playing 80s disco music, and people began to dance. A young couple spins in a small opening in the crowd. The woman smiles slightly, her eyes almost closed, as her partner in a loose dress shirt and blazer turns her. Around them, people are clapping.

It is a photo that captures a side of the pro-democracy movement often overshadowed by what came after – the brutal military crackdown on the evening of 3 June and morning of 4 June. There is no official death toll but activists believe hundreds, possibly thousands, were killed.

More than 30 years later, Zhou Fengsuo, a student leader in Beijing who was later jailed, remembers the scene. “There was a lot of celebration. For the first time, you see this freedom in the air, that inspired people to celebrate to be hopeful and be joyful in Tiananmen Square, the symbol of power in China. That’s the most inspiring story of 1989.”

Related: Hong Kong braces as protesters plan to defy Tiananmen vigil ban

Throughout the six-week occupation of the square, there were many lighter moments: protesters giving out birthday cake, people sharing breakfast and tea, someone giving another demonstrator a haircut. Unofficial weddings were held.

“Tiananmen was China’s Woodstock without mud but plenty of blood,” says Rose Tang, who attended the protests in Beijing as a university student. “It was the first time for the Chinese since 1949 to truly have a little taste of freedom as individuals and a taste of organic community spirit.”

But by the end of May, the protests had begun to wane and protesters were tense. Authorities had declared martial law on 20 May, to stamp out the weeks of marches, sit-ins and hunger strikes led by students who had inspired sympathy and support across the country. Troops had tried to move into the capital where they were blocked by civilians. There had been rumours the night before that the Chinese military would soon clear the square.

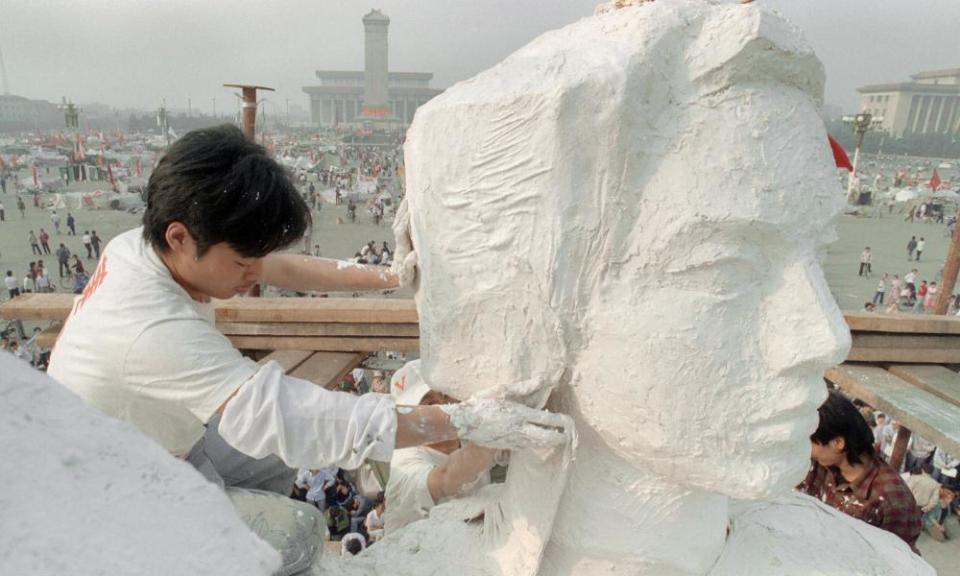

On the morning of 1 June, those who stayed overnight to guard the square were relieved to find their tents and the Goddess of Democracy, erected just a few days earlier, still standing. “When they woke the next morning and the army didn’t come. There was this exhilarated feeling of, ‘we survived,’” says Mark Avery, who was the staff photographer for the Associated Press at the time, who took the picture of the couple.

That day would be one of the last moments of peace in the square. Children gazed up at the 10-metre tall Goddess of Democracy, made of wire and papier mache. Students, workers and residents talked and sang songs according to Jiang Shao, another former leader of the protests, who was there in the afternoon. “These scenarios were very rare after martial law,” he says.

After the crackdown, or the June 4 incident as it is now described in China, such scenes were expressly forbidden as authorities moved quickly to erase the chapter from the public memory.

“The thing that really floored me was the Orwellian silence afterwards,” says Avery, who stayed in Beijing until 1991, working under martial law that was kept in place until the year after the crackdown. “Afterwards, everything out of people’s mouths was the party line. Nobody was having conversations. It was just mind boggling.”

Today, 31 years later, it is unclear what happened to the young dancing couple in the photo taken by Avery. They were not prominent student leaders. Most likely, they were university students from outside Beijing, based on the little pins visible on their shirts. The students in Beijing tended not to wear theirs, according to Zhou.

They may have been caught up in the violence or arrested. If they escaped and live in China today, it is likely they have moved on, helped by the government’s glossing over of the events.

“We don’t know. We’ll never know. I don’t know if they would still remember this day,” Zhou said. “They were just ordinary people.”