Today’s white working-class young men who turn to racist violence are part of a long, sad American history

In recent years, the United States has seen a surge of white supremacist mass shootings against racial minorities. While not always the case, mass shooters tend to be young white men.

Some journalists and researchers have argued that class and ideals of white masculinity are partly to blame.

This argument is not surprising. Throughout U.S. history, white men’s anxieties over their manhood and social class help explain many violent attacks on Black people, whom the perpetrators blame for denying them their rightful privileges.

Such was the case with Dylann Roof, a then 22-year-old white supremacist who was convicted and sentenced to death in the 2015 deaths of nine Black worshippers at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

In another case involving a racist mass shooting, Payton Gendron, a white supremacist who believed a slew of racist conspiracy theories he discovered online, was sentenced to life in prison after his convictions on the 2022 murders of 10 Black people at a Buffalo, New York, grocery store in a predominantly Black neighborhood.

One such unfounded conspiracy that then 18-year-old Gendron frequently cited was the “great replacement theory,” the false idea that a group is attempting to replace white Americans with nonwhite people through immigration, interracial marriage and, eventually, violence. Such ideas reflect white supremacist beliefs, but they also reveal deep insecurities about white men’s social status in America.

It’s my belief as a scholar of U.S. history, labor, ethnicity and masculinity that Roof, Gendron and other recent mass shooters in racist attacks share similar insecurities with their historical predecessors.

Though finding solutions is not an easy task, recognizing the link between white anxiety and racial violence is a first step in addressing the problem.

Class, masculinity and violence

In modern-day society, young men face many hurdles to traditional avenues of masculine success. It’s more difficult than ever for young people to purchase a home, secure a high-paying job or find a marriage partner. These difficulties result in a great degree of anxiety among young people who struggle to achieve the security of their parents’ generation.

Many young men become particularly resentful of these conditions. Male socioeconomic power is traditionally linked with patriarchal authority, a position to which many white men may feel they are entitled.

Throughout American history, white manhood was often defined “through the subjugation of racialized and gendered others,” according to historian Eduardo Obregón Pagán. But when they felt their superiority was threatened, white men acted against the supposed enemies whom they felt blocked them from enjoying these benefits of their white male privilege.

The 1863 New York City draft riots

During the Civil War, northern states like New York instituted a lottery draft of fighting-age white men. At the time, Black men were exempted from the draft because they were not considered U.S. citizens.

The draft infuriated the white working-class population of New York in part because rich white men could hire a substitute or pay $300 to secure an exemption to the draft. This sum was roughly the average yearly salary of an American worker.

In response, thousands of white workers rioted between July 13 and July 16, killing over 100 people. They concentrated their attacks on African Americans, whom they beat, tortured and killed. Most egregiously, rioters burned down the Colored Orphanage Asylum, which sheltered over 200 Black children.

In one particular display of gendered symbolism, a 16-year-old white youth dragged a Black corpse through the street by his genitals.

The rioters’ anger over their subordinate social class largely drove their attacks against Black men who were an easier target than the real cause of the draft inequalities – elite white men and government agents.

The 1919 Chicago race riot

During the turn of the 20th century, the Great Migration saw many southern Black people move from the rural South to northern cities like Chicago. As waves of Black people moved into the city, white Chicagoans on the city’s South Side began bombing campaigns against Black-owned homes to keep them out of white neighborhoods.

In July 1919, a Black teenager inadvertently drifted into what was considered the white section of Lake Michigan. Angry white people threw rocks at him and he eventually drowned. The incident sparked the infamous Chicago race riot, which left 38 people dead, most of whom were Black.

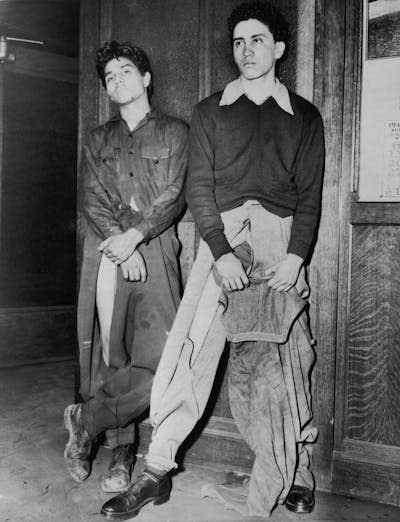

The main perpetrators of riot violence were organized white youth gangs operating under the moniker of “athletic clubs,” a phenomenon that is the primary focus of my own research. While these clubs participated in athletic competitions, they were, in effect, violent gangs who targeted Black men.

These gangs prowled the streets in automobiles and attacked African Americans, burned black homes and businesses, and kept the fires of racial violence inflamed for days. They blamed Black men for invading their communities.

Many of the youth gang members were the sons of Chicago packinghouse workers and did not want to endure the menial wage work of their parents. Unable to secure social and financial success through legitimate means, such youths turned to crime and violence to make money and build a sense of masculine identity.

Instead of traditional notions of manhood centered on the family, they internalized what historians call “rough masculinity,” which prioritized fighting and physical toughness.

The 1943 Los Angeles Zoot Suit Riots

During World War II, the U.S government rationed many foods and materials for the war effort. One such item was fabric, which forced clothing designers to fashion clothes using less material.

Most Americans embraced wartime rations, viewing sacrifice as their patriotic duty. But in communities on the West Coast, young Mexican American men flaunted flamboyant “zoot suits.” Zoot suits were brightly colored and distinctly flashy, but more importantly, they required a large amount of fabric.

White Americans viewed the zoot suits as a mockery of the war effort. On June 3, 1943, a series of riots broke out in Los Angeles as white servicemen attacked young Mexican Americans sporting zoot suits.

Demonstrating their fury over the clothing, servicemen stripped the suits off many victims and burned them. Over the course of three days, over 150 Latino men were injured, but the police did not arrest a single white serviceman.

In many ways, the zoot suiters challenged the masculinity of the servicemen. On one hand, the white men felt affronted by the Mexican Americans’ audacity to scoff at their manly sacrifice to go to war. On the other hand, by attacking the zoot suiters and ripping off their clothes, the servicemen effectively denied their claims to manhood.

There are many parallels between racial violence of the past and mass shootings of today. Understanding anxieties about class and masculinity can perhaps go a long way to addressing such concerns in a new generation of young white men.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Colin Kohlhaas, Binghamton University, State University of New York

Read more:

Colin Kohlhaas does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.