Top cancer specialist explains why it’s time to rethink what stage 4 means

Sixty years ago next month, in the Welsh town of Port Talbot, Chris Evans received his very first chemistry set for Christmas. “I was six years old. A naïve little Welsh boy, and I thought that I was going to cure all the cancer in my street,” remembers the eminent scientist and co-founder of the Cancer Awareness Trust.

Back then, he says, it felt like cancer was responsible for so many deaths around him that he decided he was going to cure it. “As a little boy, I remember my mother would become upset because another mum across the street was dying of cancer. Or my dad would tell me that John up the road was going to die soon, because he had cancer. I was always into science as a little boy so I decided I was going to create a potion, shake it in the plastic tubes in my chemistry set, and cure all the cancer around me. That was my aim. By the time I was 12, I realised I probably wasn’t good enough, and nor was my little chemistry set.”

Perhaps the latter is true, but he’s certainly spent his life working towards his original goal. Now 65, Evans, who was knighted in 2001, is a world-leading cancer scientist and one of the best-known names in biotechnology, launching several health companies, including Celsis and Rutherford Health.

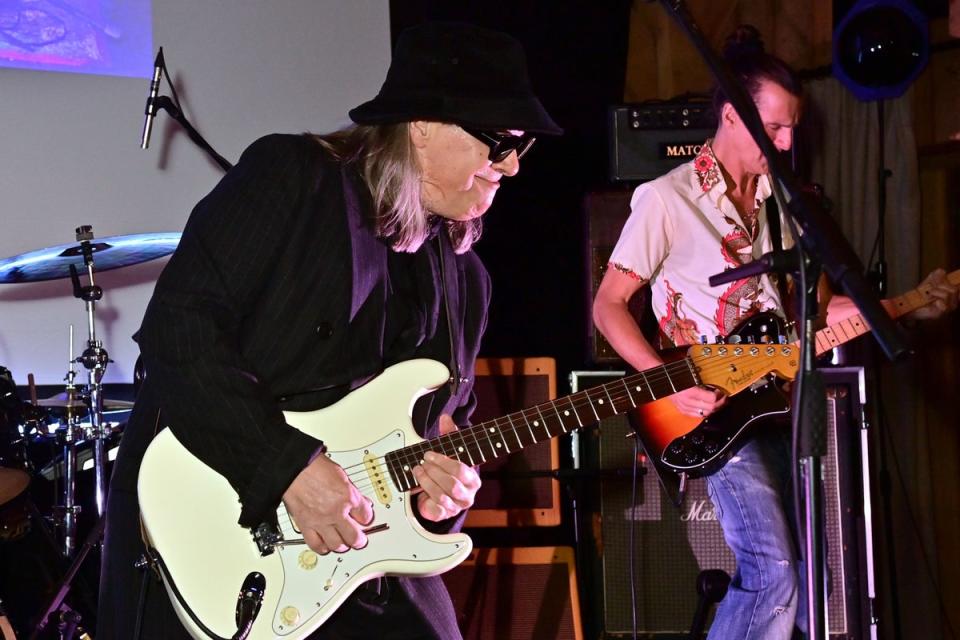

One of the treatments he works with is Lutetium-177, or Lu-PSMA, a radioactive therapy used intravenously to target cancer cells, that he identified as an option for Duran Duran’s Andy Taylor. The band’s 62-year-old guitarist was diagnosed with incurable stage 4 metastatic prostate cancer in 2018, but earlier this summer told an interviewer: “I was classified as palliative, end-of-life care. And now I’m not; I’m asymptomatic.” Of Evans, he says, “He’s a genius. I call him the Elon Musk of cancer.”

Taylor has said that his lowest point was six weeks after his diagnosis: “When it really sinks in. You’re gonna have to say goodbye to your family.” He is hoping this will be a long way off yet.

There was a time, says Evans, when being diagnosed with stage 4 cancer was something of a death sentence. “Yet people are now living longer and more comfortably than ever before, possibly for decades, with a chronic condition of cancer.”

According to Cancer Research UK, number staging is used to divide cancer into grades. Stage 1 means the cancer is small and contained within the organ it started in. Stage 2 means the tumour is larger, but still hasn’t spread into the surrounding tissues. Stage 3 means the cancer has started to spread into surrounding tissues and lymph nodes. While stage 4 means the cancer has spread to another organ altogether, and is also known as metastatic cancer.

“Fundamentally, the reason why stage 4 has always been difficult to treat is because it means the original cancer has had time to evolve and spread around the body,” says Dr Sam Godfrey, research information lead at Cancer Research UK. “The longer a cancer is left, the longer its cells have to evolve. With stage 4, genetically speaking, there may be hundreds of different cancer cells within a tumour, which then start to break away and spread around the body, squirming and burrowing into different parts.”

Dr Godfrey says these cells can often slip “behind barriers” that protect them from chemotherapy, or into the bones, where they “tended to stay”, making many treatment options, until now, limited. “So stage 4 really used to be thought of as a death sentence. But things are improving drastically all the time.”

Mainly because of the advances in treatments, and how they’re used: “There are so many new and different types of drugs,” he says. “While people with stage 4 cancer used to move to palliative care, now we’re finding new drugs that are keeping pace with their disease. By the time one drug stops working, another one has come out, which we’ve lined up for the next stage of their treatment.”

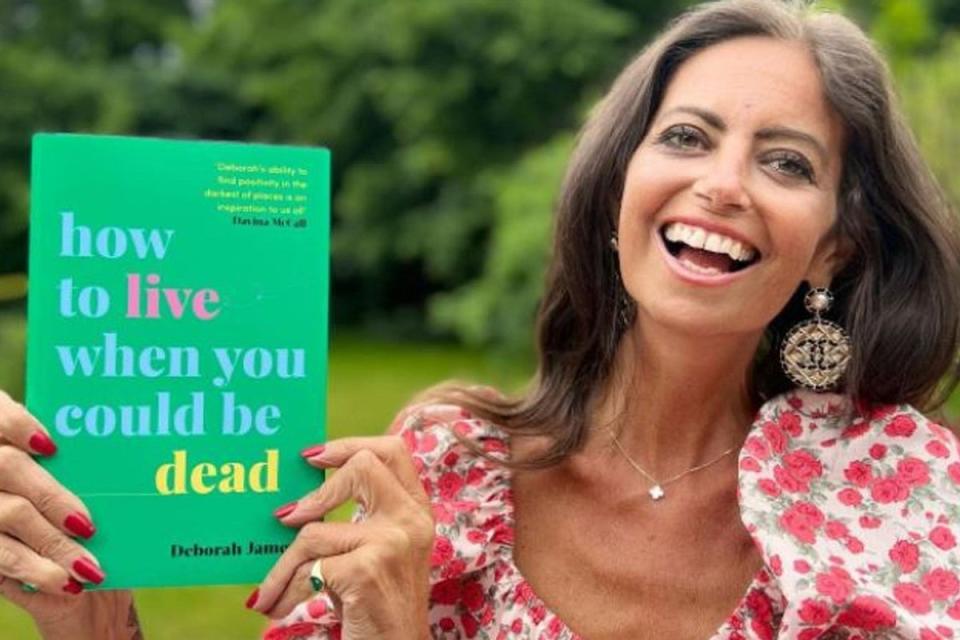

Dr Godrey cites the cancer campaigner Deborah James, who died aged 40 in June 2022, after being diagnosed with stage 4 bowel cancer in 2016. She began taking panitumumab, which since 2017 has been offered in combination with chemotherapy to treat those with RAS wild-type, a form of bowel cancer that affects just over half of patients.

Panitumumab works by targeting a specific protein in the tumour, and James credited it with keeping her alive long after her terminal diagnosis. It isn’t known exactly how much extra time the drug gave her, but in 2021 she wrote, “Don’t get me wrong, this is no cure. Rather, it’s the kind of miracle drug that gives people like me more time. More time with our husbands, kids, family and friends.”

I was classified as palliative, end-of-life care. And now I’m not; I’m asymptomatic. He’s a genius. I call him the Elon Musk of cancer

“This is what we’re seeing with stage 4 cancers,” says Dr Godrey. “While stage 4 is rare to cure completely, I’ve met people who are still living with their tumour 15 or 20 years after diagnosis. And I think this is going to become increasingly common.

“For another chunk of people with later-stage cancer, their cancer will turn into a long-term chronic condition that will be managed by drugs. Medically, that’s within our grasp. That’s where research is taking us.”

Another reason is that treatments are becoming smarter and more targeted, and based on the specific genetics of the tumour. “Rather than throwing a drug at you because you have cancer in one area of the body, doctors are using guided treatments,” says Dr Godfrey. “One of the big challenges was when prostate cancer went into the bones. It was hard to get out and treatments like bone marrow transplantation were quite unpleasant. With the new precision treatments, like radioisotope therapy, they work by beaming radioactive substances through the tumour, like a small but intense spotlight on a stage.”

One such treatment is Lu-PSMA, the type Andy Taylor had, which is delivered via an intravenous drip to “seek and destroy” cancerous tumours, sparing the healthy tissue surrounding it and reducing side effects. Scientists believe it could one day be used to treat breast and lung cancer. The health watchdog Nice is due to announce soon whether it will be approved for use on the NHS for late-stage prostate cancer (Taylor had it privately).

Andy Phillips, a 59-year-old engineer from Lincolnshire, has just passed his 10-year anniversary of living with stage 4 prostate cancer. “I was 48 and had visited my GP with a stye, but my wife, a former nurse, was more concerned with my increasingly frequent peeing, and told me to mention it,” he says. “My GP was also less concerned with the stye, and tests revealed I had terminal cancer. I was absolutely devastated. With being staged so high, I just thought, OK, this is it.”

After a radical prostatectomy, which is the surgical removal of the prostate, Andy had seven weeks of intense radiotherapy. “Before my diagnosis I was always running and cycling, so once I’d recovered from my operation I continued cycling all the way through my radiotherapy, which I think helped. We’ve always eaten well, but after my diagnosis we threw out all the crap in our cupboards and made our meals from scratch.”

He says the hardest part of living with stage 4 cancer was the mental toll. “Nobody talks about that bit. How hard it is to face an uncertain future. Luckily my doctor put me in touch with Maggie’s, which has psychologists around the UK. With meditation and mindfulness, my counsellor has helped me to live in the present, and not race ahead to the future where all my fears are. Not knowing what is going to happen to me has been the hardest part.”

In many ways, stage 4 cancer is slowly becoming like HIV. That was once a life sentence, but now it can be well managed with maintenance medication and has become a chronic condition that people live with. My aim is that cancer will be the same

Chris Evans

Nina Lopes, who was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer in 2018, aged 36, agrees. In 2021 an MRI scan revealed her cancer had returned and was stage 4. “When you’re diagnosed at stage 4, you live scan to scan,” she says. “But we also want to live, we have energy, and the power to be our own advocates. I feel extremely lucky, because here I am two years later and the disease has stayed in my lymph nodes. For this reason I’m taking part in clinical trials because it might help somebody else further down the line, and I’m currently trialling two drugs that when combined have shown promising results with triple negative, called palbociclib and avelumab, at the Royal Marsden in London.”

This year Nina trekked across Jordan, something she could never imagine doing after her devastating stage 4 diagnosis in 2021. “I left that room feeling like it was the end. Never in a million years did I think I would still be here. But there are times I can’t help thinking, when will it be me? And I’ve had therapy to deal with that. The mental toll of living with terminal cancer is very hard. But no one can tell I’m a stage 4 cancer patient when they see me going on treks, or taking my daughter to school.”

Likewise, Andy Phillips has been to Tenerife several times since his diagnosis: “I’m a keen cyclist, and I’ve ridden up Mount Teide in Spain three times with stage 4 cancer.” However, his chemo has now stopped working and Andy is currently receiving no treatment, but he’s trying to remain positive. “We’ve made contact with the palliative care team and I’m now on the part of the cancer journey I don’t want to be on,” he says.

Dr Godrey says that another big area in late-stage cancer treatment is immunotherapy, which is available on the NHS for certain cancers and works by helping our immune system to recognise and attack cancer cells. “It doesn’t work for everybody, but if you can harness the power of the immune system it can be more than a match for cancer. The challenge is now making it work for everybody.”

And, of course, it’s important to note that some patients don’t live for a long time with a stage 4 diagnosis, with many factors at play, including the type, size and location of their tumour, and how well they respond to drugs, if at all.

Evans says that while his trials have seen excellent results with breast, prostate and testicular cancer, there are still certain types, like pancreatic, that are still very hard to treat. “We have a long way to go before developing any real precision treatments for that.”

But overall, things are moving in a hopeful direction. “I’ve currently got seven new drugs in clinical trials,” he says. “And I increasingly see patients with stage 4 cancer getting on with their lives, albeit taking pills.

“In many ways, stage 4 cancer is slowly becoming like HIV. That was once a life sentence, but now it can be well managed with maintenance medication and has become a chronic condition that people live with for a very long time. My aim is that cancer will be the same.”

It may not be the outright cure he was hoping for as a boy sitting in science class, but helping many people live longer with a disease which can be effectively managed might just be the next best thing. For now.